Rising sea level in a changing climate

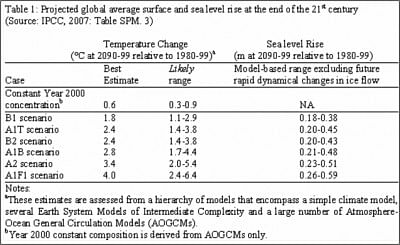

Advances in climate change modeling enable us to obtain best estimates of temperature, rainfall, and sea level and their likely uncertainty ranges given a projected warming with different emission scenarios. Results for different emission scenarios are provided explicitly in the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) report. Projected global average surface warming for the end of the 21st century (20902099) relative to 19801999 with best estimates and likely ranges for global average surface air warming for six Special Reports on Emission Scenarios (SRES) are shown in Table 1. The model-based projections of global average sea level rise at the end of the 21st century (20902099) are also shown in Table 1.

The models used to date do not include uncertainties in climate-carbon cycle feedback nor do they include the full effects of changes in ice sheet flow, arguing that they could not yet be modeled, and consequently do not present an upper limit of the expected rise. While the projections include a contribution due to increased ice flow from Greenland and Antarctica at the rates observed for 1993 to 2003, they do not include the dynamics of flow rates that could increase or decrease in the future. For example, according to many recent studies, if this ice flow contribution were to grow linearly with global average temperature change, the upper ranges of sea level rise for the SRES scenarios shown in Table 1 would increase by 0.1 to 0.2 m. Observations have already revealed that, without the contribution of ice flow, global average sea level rose at a rate of 1.8 [± 0.5] mm per year over the period from 1961 to 2003. With the contribution of increased ice flow at the rates observed from 1993 to 2003, the average sea level rose about 3.1 [± 0.7] mm per year.

So, what I want to emphasize here is that the IPCC-Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) did not include the full effects of rapid ice flow changes in its projected sea level ranges. More clearly it can be mentioned here that the IPCC projections for future sea-level rise were based on thermal expansion only, without giving adequate considerations to the consequences of future ice melt. It is very important to note here that the same IPCC report concluded that thermal expansion can explain about 25% of observed sea level rise for 19612003 and 50% for 19932003, but with considerable uncertainty. The remainder is mostly caused by ice melt. Other climate-induced changes in land water storage likely played a minor, but not negligible, role. A recent analysis concludes that during 20032008 the relative contributions were 20% for thermal expansion and 80% for ice melt. While a 5-year period is likely to be dominated by natural variability, there is some reason for concern that ice melt could make an increasingly larger relative contribution in the course of this century.

Considering the dynamic effect of ice-melt contribution to global sea level rise, several new studies have estimated that by 2100 the sea level rise would be approximately three times as much as projected by the IPCC-AR4 assessment. Even for the lowest emission scenario (B1), sea level rise is then likely to be about 1 m and may even come closer to 2 m. However, despite uncertainties, recent studies have emphasized that we have to consider the possibility of faster sea level rise than suggested by the IPCC-AR4 assessment. In fact, the writer and his team have already observed a faster rate of rise of sea level in the vicinity of western Pacific islands. At this stage we have reasons to believe that snow-melt is a major cause for this faster rate of rise in these small island countries. This will continue to be a factor and, as a consequence, if we can incorporate the dynamic effect of snow-melt in our projection the rise will be faster, resulting in considerably higher final rise values than the IPCC projections in different horizons, 2010 to 2099, regardless of the exact amount.

With regard to implications for the future, the critical question is what can be done to help, support, or even save, the vulnerable communities in the Asia-Pacific region. We recognize that there are no easy answers, but some immediate responses are justified. Current events are already dire and the future outlook, even more so. Some possible options include adaptation and mitigation. Adaptation is a local and regional scale response justified by current events. Mitigation of projected extreme sea- level rise is a geopolitical problem requiring consensus policy goals and exceptional international agreement. This is a challenging task and even the author is not sure in his optimism over this future.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments