Women and animals in Byron's life

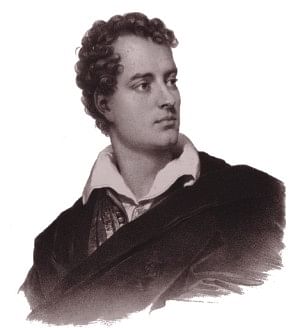

Let us suppose for a moment, in an on-going teaching session on the English Romantic poets, a traditional teacher asks his or her learners: "Can you accurately spell out the full name of Byron?" What may be the potential responses? My present experience as a university teacher in English suggests, at least eighty per cent of them will fail to give a right answer. It is not because the name is difficult but because today, very few students have the propensity to research into writers they study in each semester. Moreover, forgetting names of writers, teachers, relatives, friends, colleagues and acquaintances is now almost endemic in casual learners. Senior English teachers will certainly bear me out that it had been customary in our time to dig out the essential details of writers' lives before their texts were taken up for explication. However, let me answer the question for those who stumble in recalling Byron's name in full. It is George Gordon Lord Byron who was the most 'flamboyant' among the British poets and is rated as a true embodiment of literary Romanticism.

Lord Byron still remains an enigmatic and controversial figure to critics and students of English literature. He became a subject of intense interest to biographers for many reasons. In the words of Richard P. Dean, "His colourful aristocratic ancestry, his reckless and defiant spirit, his scandalous separation from his wife and subsequent exile in Italy, his death after joining the Greek revolutionaries in their fight against Turkey" became the subjects of ceaseless inquiry. Ernest Boyd described Byron as "the rake, the daredevil, the rebel." G. Wilson Knight finds in him the virtues of "chivalry, courtesy, humility and courage." Mary Shelley, wife of another Romantic poet P B Shelley, described her family friend Byron as a "fascinating, faulty, childish, philosophical being."

The only son of his parents, Byron became an orphan when he was only three. He began life in a poverty-ridden family governed by an angry but affectionate widowed mother. Initially, Byron survived barely on private tuition but within years fortune smiled upon him when his renown as a poet began to spread far and wide. His autographical monologue, Childe Harold, and a continuous flow of publications began to fetch him huge income.

Two dominant traits, however, surfaced in the character of Byron: his love for women and love for animals. Love for women received precedence before critics whereas his love for animals, a unique virtue, remained unrevealed when his character was gauged by teachers, critics and students.

Byron was held guilty of promiscuity as reportedly he had involvement with more than two hundred women. Mostly accosted by fashionable infatuated ladies, Byron got involved in a series of love affairs. Although Byron had a deformed right foot resulting from a physician's mistreatment, both local and foreign ladies felt attracted to him for his aristocratic lineage, gregarious demeanour, witty conversation, sexual precocity, and above all, his seductive appearance. Byron was conspicuous not only for his "so beautiful a countenance" but also for his scholarship. Educated at Cambridge, he digested "about four thousand novels, including the works of Cervantes, Fielding, Smollett, Richardson, Mackenzie, Sterne, Rabelais, and Rousseau." He was then only nineteen.

When Byron was only seven, he fell in love with his cute cousin Mary Duff who, after ten years of relationship with Byron, got married to another man. At home he fell in love with a cousin Margaret Parker who ignited in him the fire of poetry. At fifteen, he fell in love with yet another cousin, Mary Chaworth, for whom Byron used to nurture deeper feelings. He also became close to his half-sister Augusta Leigh, although later she got married to her own cousin. When Byron was still planning an elopement with Augusta, Lady Melbourne convinced him not to do it.

In 1813, he had a brief, 'platonic' affair with Lady Frances W. Webster, who became the subject of gossip for her scandalous affair with the Duke of Wellington. As Lady Webster and Byron staged a parting, Byron kept it on record in his poem "When We Two Parted":

When we two parted

In silence and tears,

Half broken-hearted,

To sever for years,. . .

Long, long shall I rue thee

Too deeply to tell.

As I mentioned earlier, his Childe Harold brought an irresistible flow of female admirers of whom Lady Caroline Lamb stood conspicuous for her social rank. Caroline, whom Byron dubbed as a 'volcano' and who was already married to the Hon. William Lamb, developed an infatuation for Byron. William could sense it but did little to dissuade her wife. However, Caroline was shocked to know that Byron had in the meantime won a 'new conquest' involving Lady Oxford. When she requested him to keep Lady Oxford out, Byron replied: "It is impossibleshe comes at all timesat any timeand the moment the door is open, in she walks---I can't throw her out of the window." Caroline later ended her affair with Byron, an act that prompted her to produce a novel, Glenarvon, where she depicted Byron as the evil. Biographers report she caused considerable mental distress to him. As psychic relief, compensatory measure, and persuaded by Augusta, Byron married Ann Milbanke. Belonging to a fully discrete discipline and mindset, Ann did not prove a true match for an impulsive and volatile Byron. Ann, a mathematician, faced a tough time getting along with the moods and needs of an exceptionally romantic husband like him. After fifteen months, the ill-starred marriage ended in a formal split. With Shelley and Mary Shelley, Byron was already intimate, and in the process, he came in touch with Mary Shelley's step-sister Claire, who "forced herself on Byron" and bore him a daughter Allegra, who died of fever at five.

The above events may suggest to casual readers the "frenzied debauchery" of Byron but then another side of him remains unknown to many --- his constant and spontaneous love for animals. Although not truly a match for Byron, Coleridge had similar love and fascination for animals, which was manifest in his deathless poem The Ancient Mariner. Most of Byron's letters, numbering about 3000 and written to a host of friends, bear enough testimony to his uncommon love for animals. In conversations with friends, he used to express genuine concern for animals whenever they became indisposed. For example, when his most favourite dog Boatswain was attacked with rabies, he nursed him, sponged his foaming jaws with unprotected hands. Newstead Abbey, Italy, where Byron migrated, later became a new home for hedgehogs and tortoises brought from Greece. When a goose was decaying from sickness, Byron fed it with his own hand.

Wherever he shifted --- to Venice, Pisa --- he carried and maintained his menageries. At Cambridge, where keeping dogs was prohibited, Byron kept a tame bear in a turret at the top of a staircase. During his trips to Italy, he used to take his dogs with him. Those who took animal-hunting as a sport were condemned by him. He rebuked even the clerics for indulging in fox-hunting exploits. This virtue was admired by Byron's married Italian mistress Teresa Guiccioli as a "weakness of a great heart." How he used to detest fishers for their cruel fishing is manifest in the following lines of his masterpiece Don Juan, a satire against modern civilisation :

And angling, too, that solitary vice,

Whatever Isaac Walton sings or says.

(Lines 845-846)

Byron wanted that all the caged birds of the world should be unbound to let them enjoy resort to nature. Byron's soul must be contented to know that today voices are being raised across the world for the abolition of zoos everywhere, and for championing installation of safari parks to let animals move free in a natural environment.

When his dog Boatswain died, Byron buried him in the same way a lover buries his beloved, and put a tombstone inscribing therein: "Near this spot are deposited the remains of one who possessed beauty without vanity, strength without insolence, courage without ferocity, and all other virtues of man without his vices." This unusual act unduly earned for Byron the disgrace of being a misanthrope, and he became at once the subject of derision and admiration.

Unhappy in wedded life, and tired of being pampered by scores of adoring ladies, Byron chose to live an exiled life. He left England for ever in 1816 and began making trips one after another to Portugal, Greece, Italy, Albania, Brussels, Switzerland, Malta, in quest of fresh fortune and peace. At thirty-six he, a staunch advocate of liberty, sought to join the struggle to free Greece from Turkish domination. He contracted a fatal rheumatic fever that cut his life short; and the many more poetic resources that were yet to spring from him ceased for good. In 1824 Byron died in Greece. Through his sufferings and agonies created partly by circumstances and partly by self-indulgence, and by dying an untimely death, Byron has taught us that frivolity and promiscuity may provide temporary delight but it ultimately ruptures life itself, and that a wrong, abrupt, and emotive choice of a life partner may make one's life hell here on this very earth.

The words Byron inscribed on his dead dog's tombstone are best suited for the poet's own epitaph as --- "beauty without vanity, strength without insolence, courage without ferocity" --- depict much of his character. George Gordon Lord Byron embodies the Romantic essence and remains a brilliant enigma to his readers and admirers even today.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments