Of books and power

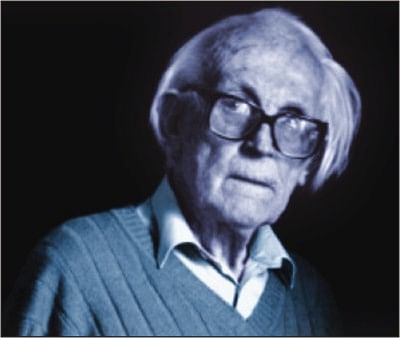

MICHAEL Foot

Michael Foot was a brilliant intellectual who also happened to be a politician. In an earlier era, he might have been a philosopher-king or a wise counsellor to a monarch in the best traditions of history. You could think here of Merlin in that old tale of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. There was a profusion of wisdom in Merlin, something which only reinforced itself when one day he chose to venture a metaphysical explanation of a spate of gloom in the king. When Arthur looked out the window and intoned, sadly, "It is a dark day, a troubled day", Merlin told him in dispassionate manner, "It is a day, just a day, my lord. You have a dark and troubled mind."

And that is how it is with men who think. And they think because they read. Michael Foot read all his life, even as he made all those advances in politics. He never made it to 10 Downing Street as Britain's prime minister, for the times and the trends were against him. But he was shrewd enough to understand that one of the fundamentals for one who gives himself over to politics is a necessity for cultivating and nurturing the intellect. And you do that through reading, loads of it. And yet Foot knew of the limitations political men (and women) were faced with, impediments that kept them away from reading. No matter. Reading for politicians was still a great desirable. "Men of power," said Foot, "have not time to read. Yet men who do not read are unfit for power." There is substance in that statement. The proof is all around you.

Begin with America, where the emergence of Barack Obama was in essence the return of intellectual vigour to the White House. Even if you have not read Obama's books (Dreams from My Father and The Audacity of Hope), you have heard him speak. And his speeches leave you in no doubt that a man who can fashion words and sentences in such a literary pitch is a man who spends his waking hours perusing the pages of books. Has reading made Obama a better politician? The obvious answer is yes. He convinces you, after eight years of Bush-Cheney, that political power in the United States once more identifies itself with high intelligence and unmitigated intellectualism. His administration is a charming coming together of a tribe drawn from the corridors of academe.

Note, though, that reading may not necessarily accord greatness to a politician, to one wielding political power. Woodrow Wilson's academic background in the end did not serve him well in the White House. Congress threw out his ideas of a better world order consequent upon the establishment of the League of Nations. Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter, surely two of the most brilliant presidents of the United States because of their wide reading and forensic analytical abilities, eventually fell prey to fate, the former for his suspicious nature, the latter for his naivete. Bill Clinton, with a powerhouse of a mind and with his ceaseless reading, could have made a better leader had his peccadilloes not come in the way.

Be that as it may, the enormity of reading that Nixon, Carter and Clinton went into all their lives will leave them with better reputations than those of some of the men who came before them . . . and after. Where reputation is the issue, Jawaharlal Nehru's reading, eclectic in dimension, served as wonderful preparation for him as a leader. Had he not been a politician, Nehru might well have been a full time scholar. But, then, he was a scholar-politician whose reading was good enough for him to take a sure path to writing. That is what you can also say of Moulana Abul Kalam Azad and Gandhi, but not of Mohammad Ali Jinnah. We are not aware of Jinnah's reading habits and there is little in his public pronouncements to suggest that he had time for anything other than raw politics. There was a bluntness to his character that sat ill with one about to found a state. Compare that with the scholarly man that was Harold Macmillan. On taking office as Britain's prime minister in 1957, he told a friend that he would now have ample time to read. Macmillan read all the time, even during the few minutes when he could break off from debates in the House of Commons or in the brief moments he could snatch at Downing Street for a quick plunge into books. Macmillan did not become a great leader. But his formidable intellect, strengthened by avid reading, would propel him one day into the job of chancellor of Oxford University.

Foot's belief that men who do not read are unfit for power has not always turned out to be the truth. Men who have read have held power, yes. But they have hardly brought to power the intellectual shine which ought to have been a product of their wide reading. Stalin and Hitler were both avid readers, collectors of volumes spanning the ages. And yet their hold on power was made possible by the fear they drilled into their nations and their political associates. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto read voraciously and yet gave precious little sign that his books had made him a scholar or a better politician. In his pursuit and exercise of power, he was feudal, the class he was born into. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman read selectively and Tajuddin Ahmed was always into profound reading. Both men were able to relate their intellectual accomplishments to their political struggle for a free country for their people. Fidel Castro reads profusely. Che Guevara and Salvador Allende could not stay away from books just as Tanzania's Julius Nyerere could not.

Towards the end of the last century, Bangladesh's President Shahabuddin Ahmed publicly suggested that the nation's political classes go into reading, prompting the prime minister to acquaint the country with news of the reading she had been going through. Francois Mitterrand read prodigiously, a habit that translated well into his conduct of the French presidency. He was at the Elysee for fourteen years and gave it a distinctive flavour of the scholarly. John F. Kennedy did not run a grand administration. Nor was his White House really a recreation of Camelot. He could read at great speed, but he read very little. The saving grace was the intellectual retinue that defined his new generation politics --- Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Kenneth O'Donnell, Pierre Salinger, Robert McNamara et al.

Abraham Lincoln's passion for reading made him a great president and a greater statesman. And his best friend? Here's Lincoln in his own words: "The things I want to know are in books; my best friend is the man who'll get me a book I ain't read."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments