<i>The letters of John Keats . . .</i>

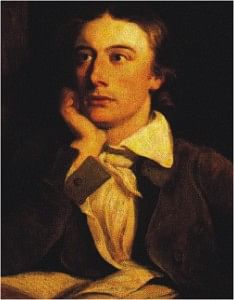

England, once dubbed as the hub of literary activities and as the "nest of the singing birds", produced in the later part of the 19th century a poet who was ambitious of being among the English poets and who became almost as famous as Shakespeare. He was John Keats, a very familiar name to the students and readers of English Literature.

A few exquisite poems that sprang out of his prolific pen are enough to win him immortality. But the letters of John Keats to his brother, half-brother, sister, friends and acquaintances are as important as his poems because they mirror more authentically his real self, i.e., his personality. The letters should not be viewed merely as casual correspondence. These are in fact the record of his brief but eventful life and the repository of his poetic and philosophical ideas. These letters reveal him as an affectionate brother, a faithful friend, a passionate lover and a powerful literary critic. The letters of the poet, therefore, deserve our close attention and critical analysis for a complete understanding and assessment of the man.

John Keats' life was full of agonies, sufferings and unhappiness. The world he inhabited may best be described in his own words written to his friend Reynolds: "The world is full of misery, heartbreak, pain, sickness and oppression." His sufferings deepened when his mother remarried soon after the death of his father. His mother left the children in a helpless condition and also left behind an inescapable, fatal disease called consumption (tuberculosis) which Keats and his brother Tom inherited.

Keats nurtured genuine feelings of love, affection and sympathy for his brothers and sister. Himself unhappy throughout his life, Keats never shrank from showering love, sympathy and solace to his siblings. His feelings for his brother George are manifest in a June 10, 1818 letter written to his friend Bailey: "My love for my brothers from the early loss of our parents and even from earlier misfortunes has grown into an affection passing the love of women." Keats was almost obsessed with the wellbeing of his sister Fanny, who was the youngest of all and who suffered from the oppressive guardianship of Mr. Abbey after the untimely and accidental death of their parents. In a letter Keats wrote: "Your welfare is a delight to me which I cannot express. The moon is now shining full and brilliant; she is the same to me in the matter that you are in spirit... I have a tenderness for you and an admiration which I feel to be as great and more chaste than I can have for any woman in the world." Keats wrote her regularly a series of letters, roughly every fortnight. Fortunately, the complete set of letters has been preserved well in England. These letters attest to how sympathetically he could hold his pen that spilled drops of kindness for his fellow beings.

Keats' letters written to his younger brother George Keats bear evidence that he had developed fascination for three women --- Jane Cox, Mrs. Isabella Jones and Fanny Brawne. Keats grew some weakness towards Jane Cox. He admitted that he liked her but did not have any genuine love affair with her. In a letter of October 14, 1818, Keats wrote to George: "I forget myself entirely because I live in her. You will by this time think I am in love with her; so before I go any further I will tell you I am not." Keats also had a liking for Isabella Jones, whom he had met by chance. A deep relationship developed between them but that seemed to be based on mere friendship. In a letter Keats said: "I expect to pass some pleasant hours with her now and then... have no Libidinous thought about her."

It was Fanny Brawne whom Keats loved with all his heart and who happened to be his close neighbour. Fanny was like an indivisible part of his self. Unfortunately Fanny did not reciprocate his feelings. Fanny led almost an anarchic life, and this caused mental suffering for Keats. In a letter Keats said: "She is not seventeen.... but she is ignorant... monstrous in her behaviour flying out in directions." The poet had a perpetual sense of belonging to her and sought to be reassured that Fanny really belonged to him.

Loneliness overtook him seriously but he could hardly escape it. He yearned for a mate who could share equally his joys and sufferings. The poet wrote in a letter: "The hawk wants a mate so does the man.......they both want a nest and they both set about one same in the manner." Keats, the nightingale of Romantic poetry, was dreaming of building a nest of his own. Fanny had already broken his heart and the fatal tuberculosis took possession of his being in the meantime. During the last stage of his life, especially when his disease took a serious turn, the poet craved for the constant company of his beloved. But Fanny chose to remain alienated from him and remained occupied with the self-oriented activities. In 1820 Keats wrote to Fanny: "It is certain I shall never recover if I am to be so long separated from you.......I am literally worn to death which seems my only recourse."

Keats' sense of belonging to Fanny was simply overwhelming and he wanted to see that she had given up all her moral irregularities that accelerated the process of his untimely death. What was sport to Fanny was death to Keats. In the same letter Keats wrote with a bleeding heart: "If you still behave in the dancing rooms and other societies as I have seen you ... I do not want to live ... if you have done so I wish this coming night may be my last. I cannot live without you and not only you but chaste you and virtuous you ... be serious. Love is not a plaything."

Keats was a voracious reader of poetry. He spent most of his time reading and reciting poems of Homer, Virgil, Aristotle, Spenser, Shakespeare and Wordsworth. To him knowledge was at once the source of sorrow and solace. He visualised that one day Fanny would betray but poetry would not. So books of poetry were his constant companion. In a letter to his friend-publisher Taylor, Keats wrote: "I find that I can have no enjoyment in the world but continual drinking of knowledge-----there is but one way for me. The road lies through application, study and thought." Keats' poetic philosophy is confined within his search for truth through imagination. In his views on imagination, Keats appeared to be platonic. In a letter to Bailey on November 22, 1817. Keats wrote: "I am certain of nothing but of the holiness of the hearts, affections and the truth of Imagination----- what the imagination seizes as Beauty must be Truth whether it existed before or not. "This idea was echoed in one of his poems----Beauty is Truth. Truth is Beauty. Poetry was to Keats a spontaneous outburst of emotion. It comes automatically to the poet: no force can produce poetry. In a letter to John Taylor on February 27, 1818, Keats noted thus: "If poetry comes not as naturally as the leaves come to a tree it had better not come at all." The poet started his career as an apprentice to a surgeon but knives, forceps, plasters and tablets could not hold him back. He left the job and became an ardent reader of poetry. To him poetry was life and life was poetry. In a letter to Reynolds written on April 18, 1817, Keats admitted: "I find that I cannot exist without poetry, without eternal poetry. Half the day will not do---the whole of it."

As a critic he recognized the genius of Shakespeare and loved to read passages from his plays whenever he found time. The poetic sensibility and critical insight happily combined in him. In a letter to a fellow-poet named Haydon, Keats wrote: "I am very near agreeing with Hazlitt that Shakespeare is enough for us." Appreciating William Wordsworth, he wrote to Reynolds in 1818: "He is a genius and superior to us insofar as he can make discoveries and shed light in them. Here I think Wordsworth is deeper than Milton." Keats could sharply perceive the distinctive poetic features of John Milton about whom he wrote in the same letter: "He did not think with the human heart as Wordsworth has done. Yet Milton as a philosopher had surely as great power as Wordsworth."

Friendship would not remain without its impression in the letters of the poet. The circle of his friends and admirers constituted most of the remarkable minds of the period. They appreciated his genius and stimulated him to poetic exertion. Haydon, Dilkie, Reynolds, Woodhouse, Taylor, Bailey were his chief companions and correspondents. Cowden Clarke, son of a headmaster became one of his most intimate and reliable friends.

Leigh Hunt, a contemporary poet of some eminence, became a sympathetic friend of the poet. Keats' heart leaped towards him in human and poetic fraternity. In a letter to Haydon, he wrote: "I am very sure than you do love me as your very brother. I have seen it in your continual anxiety for me and I assure you that welfare and fame is and will be a chief pleasure to me all my life."

The friendship between Keats and Severn, the artist, grew at the end of 1817. Keats found his own artistic image in him; and to Severn the poetical potentials of Keats were an ever-flowing source of enjoyment and inspiration. Keats also reciprocated his friend's artistic talents and spent hours sitting beside him while he remained engaged in painting. It was with Severn that the poet went to Italy for the last time. By the end of 1820, Keats' health deteriorated and he began suffering from pain in his chest and stomach. He could well feel that the time for him to bid adieu to this world had come. In a letter to Brown, he wrote: "I have coals of fire in my breast. It surprises me that the human heart is capable of containing and bearing so much misery. Was I born for this end?" During this time Severn remained engaged day and night in nursing the dying poet ceaselessly. Keats was indebted to Severn for all he had done for him during the last moments of his life and we are indebted to Severn for preserving the last words of the poet in his personal diary. Keats breathed his last February 23, 1821. Before dying he requested Severn to put a gravestone inscribing therein: "Here lies one whose name was writ in water."

Keats was neither a pessimist nor an escapist. His poems do not reflect his true personality. Readers of his poetry will not be able assess him fully if his letters are not deciphered. In a letter to Fanny Brawne, Keats revealed his conviction that life should be faced with all its sufferings. We should, therefore, read his letters not only to appraise him fully but also to store the courage to face life with all its hazards and challenges. His life, so modestly unfolded in his letters and poetry, helps us enlarge or broaden ours.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments