Philosopher with the self-deprecating humour

The soldiers of the Pakistan army had their job cut out for them on the night of 25 March 1971. When they reached Gobinda Chandra Dev's quarters in the residential quarters of Dhaka University within hours of the commencement of the genocide, they wasted no time. They simply pumped their bullets into Dev. The philosopher, revered all over Pakistan for his insights into life and all that it symbolized, collapsed. There was no chance he would live. The life had already gone out of him. Dev's corpse would soon be dumped into a mass grave the Pakistanis had some of their victims dug. In a matter of moments, the man who had spent his living years going through one sacrifice after another --- he did not marry, he did not opt for India when the partition of the country took place --- was dead and gone. In death, he assumed a new symbolism, that of a nation suddenly pounced upon by a horde of men masquerading as politicians and soldiers come from what was then West Pakistan. Dev died that night, or in the first light of the next day, as did thousands of others, as millions of Bengalis would in the months to follow.

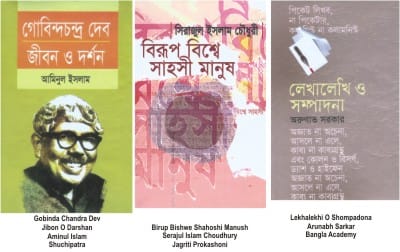

Professor Aminul Islam brings G.C. Dev, as the academic was known to all who knew him, to light once more. And that thought once more has to do with the fact that after his murder, Professor Dev very nearly came to being forgotten, owing primarily to an absence of adequate or substantive literature on him. To be sure, his was a household name. And indeed every Bengali knew that he was a teacher in the department of philosophy at Dhaka University, that he was one of the earliest of martyrs in defence of the Bangladesh cause in 1971. But with the pattern of post-liberation politics, especially that which was set into motion through the assassinations of 1975 and the subsequent rise of the forces of anti-history, it swiftly began to dawn on the public that like all other aspects of the War of Liberation, Dev would one way or the other be pushed into oblivion. From that perspective, Islam, a student of Dev's as well as colleague (he recently went into retirement from the department of philosophy), has done everyone in this country a huge favour. Obviously, the work is a clear and clean tribute to the martyred academic. More importantly, though, it is a palpable assessment of the ideals Dev stood for all his life.

Gobinda Chandra Dev died relatively young, at a mere sixty-four years. But in that brief period he packed a punch others could only be envious of. His doctoral dissertation, which he termed Reason, Intuition and Reality, in 1944 earned him a PhD from Calcutta University. So many decades later (it appeared as a book under the title Idealism and Progress), it remains a point of reference for students of philosophy. There were to be others in the years that followed, but what essentially was a factor with Dev was the ease with which he related philosophy to his life and at the same time convinced others that logical explanations of intangible reality need not be an inscrutable affair. That being the case, Dev was one man intensely involved in expanding his social links. He was, of course, a quintessential philosopher. But the difference between him and so many others of his calling was the ease with which he carried himself. He was a good conversationalist at social gatherings. His smile, which was a constant with him, endeared him to people, some of whom might be forgiven for looking for a conventional, pretty forbidding philosopher in him and not finding him. Dev loved food, which is not what you can say about philosophers generally. His humour was self-deprecating. And yet there were the serious reflections he went into, even as he moved among the multitudes, thoughts that endlessly exercised his intelligence.

In the 1960s, G.C. Dev's astute understanding of the philosophical matrix led to his being elected general secretary of the Pakistan Philosophical Congress. That was an achievement, given the communal nature of the state and given the sheer exploitation which Bengalis suffered through in Pakistan. One explanation here could be that it was his humanism which appealed to many, perhaps all. Was that humanism more idealistic than a reasoned analysis of the human condition? Suffice it to say, for now, that Dev's focus was constantly on existence as it appeared in reality. And, of course, reality was a concatenation of events and incidents that sprang from the objective conditions which defined the lives of men and women.

Aminul Islam's work is incisive, for it brings into focus a wide range of thoughts as encompassed in G.C. Dev's philosophy. In a larger sense, Dev's travels in the realm of thought could be considered a measure of the contemplations the Bengali middle class was progressively losing itself into in the decade of the 1960s. Dev's central theme was certainly not politics. But that his philosophy to a very large extent shaped Bengali nationalist politics in that exciting era has never been in doubt.

Gobinda Chandra Dev was a man head and shoulders above any other. A thinker, a Fulbright scholar, a patriot and, in the ultimate sense, a Bengali rooted to the land that had consistently shaped his intellectual landscape, he remains our pride. That pride goes up by several notches when you remember that he was a brave philosopher who went to his death testing the limits of his rational comprehension.

. . . Bravehearts in a hostile world

SERAJUL Islam Choudhury's preoccupation with history has been an endless source of satisfaction for those who have been reading him over the last few decades. His has been an intense series of commentaries on national and global events, with that certain touch one identifies with Left politics. Choudhury's pronouncements on men and events across the diverse patches of the world have by and large been marked by his empathy for those who have less, or have nothing. Briefly, he has considered the world and the history attending it to have been characterized by exploitation and one tends to agree with him. Given that the struggles waged by poor societies have regularly been attempts to free themselves of exploitation, there is the core thought that these struggles have been offshoots of the principled determination some brave men and women have put up through moving time.

And these essays in this work are but the tales of courageous individuals. That of course is what you have an idea of through the title of the book. These brave ones inhabit an inhospitable world. The brave always do that, for it is always a hostile environment that throws up men and women of character and courage. Dwell, if you will, on Ila Mitra. Who would have thought that the new state of Pakistan would so early on in its independent nationhood resort to the kind of atrocities that were to turn Mitra's life upside down? Nachol was a seminal happening for her, for those whose rights she sought to defend. But the state of Pakistan, caught in a persecution complex from which it was never to recover in its eastern province (until the province, having decided to become an independent entity of its own, ejected it lock, stock and barrel in 1971), was unwilling to tolerate any challenge to its political authority. Besides, do not forget that Ila Mitra's religious beliefs, at least where the conventional aspects of it were concerned, stood at variance with the faith upon which Pakistan had been prised out of India.

It is the courage in Ila Mitra that Choudhury recalls all these years later. She went to prison, was systematically tortured by the police and subjected to rape. The story has already been told by Maleka Begum in her impressive earlier work on Mitra (and Choudhury makes a necessary reference to it here). Serajul Islam Choudhury zeroes in on the spirit that drives Mitra, that enables her to come forth with her story and so go on with her life. Courage, as it appears to the author, has historically been an integral component of the Bengali personality. Maybe that has been a great reason why the Bengali nation has never been content with the status quo, with things as they are. Naturally, in his reflections on courage, Choudhury goes back to an assessment of the intrepidity with which Sheikh Mujibur Rahman fashioned a change in the course of politics. Mujib is part of history. The bigger truth is that he built, brick by slow brick, much of that history through his preoccupation, or call it well-meaning obsession, with the place of his Bengalis in the political scheme of things.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is the apotheosis of Bengali resurgence. One can argue with that truth only at one's peril. But there are the other personifications of Bengali determination that cannot be ignored. From such a perspective comes the story of Tajuddin Ahmed, the one man whose absence in 1971 (had it really happened) may well have meant the difference between life and death for the Bengalis. Choudhury has no illusions about Tajuddin's place in history. The wartime Bengali leader, having called forth in himself the pluck to cobble a government, now must instill an equal degree of courage in the nation he plans to steer to freedom. He does the job well. But Abu Taher? Here too is a soul unafraid to scale the peaks. As an officer in the Pakistan army based in West Pakistan, right at the moment when his fellow officers, non-Bengalis at that, were headed for 'East Pakistan' with the clear mission of sorting out the Bengalis, he was troubled by his own absence from his own land. That prick of conscience that would come to shake up all politically aware Bengalis was eventually to work in Taher as well. He found his own way of going to the war. Brave, unsullied by anything personal, he fought passionately against the very army he had been part of. And he lost one of his legs in that twilight struggle. In free Bangladesh (and here's the irony), he was to lose his life on the gallows.

The work here encompasses what appears to be a widening range of experience. Choudhury segments his story telling into the political and the cultural. In the latter category come a recapitulation of the lives and deaths of Jyotirmoy Guhathakurta and Rashidul Hasan, men whom Choudhury knew well as his colleagues in the department of English at Dhaka University. He writes with sadness but with an abundance of feeling on Munier Chowdhury and Ahmed Sharif. There is deep pathos, owing to a deep friendship that death has rent asunder, in a recalling of the man that was Giasuddin, the historian abducted and murdered by the collaborators of the Pakistan occupation army. And then there is the man in self-exile, Shamsuddin Abul Kalam. It is Kalam's endless search for a country (and he believed Bangladesh was that country) that defined his life, especially after December 1971. That search, however, only enhanced his sense of disillusionment. The country, he comes to the swift realization, has well nigh been lost. And therein he echoes another expatriate, Mizanur Rahman. A shattering truth shoots out of Rahman's Tirtho Amar Graam: 'The country has not lost us; we have lost the country.'

Shahoshi Manush deepens your sadness. And then, conversely, it does something better: it rekindles the old, comatose spirit in you, the same that once ignited your sense of pride in your heritage. Read on --- and you will know.

. . . Writing and the decline of language

THOSE in the media ought to be grateful to Arunabh Sarkar. He brings out all the flaws, all the warts, all the shortcomings that often mar the quality of journalism. Of course, in Lekhalekhi O Shompadona, he focuses on the state of Bengali language journalism and the many maladies it is prey to. But that is all the more reason why the reader could have his interest ignited in the work. There is a simple, unalterable thought at work here: Bengali happens to be the language of the state, which quite naturally presupposes the idea that those who write in it will avoid the pitfalls that Bengali users of other languages, English for instance, often come up against. But that is a thought from which Sarkar brusquely yanks us away. His work is a long litany of the many mistakes, or call them blunders, which quite often undermine the linguistic quality of a goodly number of Bengali language newspapers here in this

country.

Arunabh Sarkar begins his study of the collapse of Bengali in newspapers through pointing to the absence of a comprehensive Bengali language dictionary. It is surely undeniable that there happen to be, at this point, a fairly large number of dictionaries in the language. No matter. Sarkar remains unimpressed, and for good reason. One tends to agree with him. And why not? The mistakes or the superfluities he notices in the newspapers he has studied are those that not many dictionaries have covered. Note the following: 'Rajniti theke shore aashlen Dr. Yunus'. That is a heading for an editorial in a Bengali language newspaper. Sarkar takes exception to it. Yes, you can put in 'aashlen' in that rustic way of using the language. The more appropriate term would be 'elen'. Which makes you wonder. What other mistakes, perhaps careless, could we be making as we plod through our quotidian existence? Sarkar gives you a hint. Quoting yet another newspaper heading (Ortho o ostrer jonno Bharatiyo jongider shonge shokkhota), he tells us again how inattention to language can lower the appeal of language. It will not be 'shokkhota', says he, but 'shokkho'. It reminds you of the irritating way in which some people fall for 'daridrota' (which does not exist) rather than the proper 'daridro'.

So what you have here --- and we draw attention to the journalistic community --- is a handbook media people (and others as well) can happily refer to. At a time when a handful of people have taken it upon themselves, to our intense discomfiture, to change the way words should be used, even spelt, Sarkar's work is in more ways than one a return to old-fashioned values. Briefly, he tells us that language, any language, ought not to be tampered with. More remarkably, those engaged in Bengali language journalism ought to be fully prepared, indeed educated, where the use of language is concerned before they venture into writing. If they do not, queer might be the consequences. Why use 'oitihashik' for historian when the proper word is 'itihashbid'? And do not forget that there is quite a difference between 'onupostheet' and 'obortoman'. One who is 'onupostheet' may well appear before you at some point. But one who is 'obortoman' cannot. Read that for 'deceased'.

The author's stress on clarity and diction is evident throughout the work. You cannot play around with language or, to put it bluntly, manipulate it to suit your desires. The whole purpose of writing in newspapers is to present facts before readers in a way that does not beat about the bush, that does not needlessly seek to intellectualise things but only gives them the story as it is. Ignore this point and you run the risk of being inaudible or incomprehensible or plain asinine. And then comes the question of editing. Having been a journalist for as long as anyone can recall, Arunabh Sarkar is well placed to understand the stumbling blocks copy editors come across. For his part, he has been an effective editor, along the specifications set by Adolph S. Ochs. The reputed journalist at the New York Times had this to say about editors, 'The most useful man on a newspaper is one who can edit. Writers there are galore. Every profession offers them. But the editor is of a profession."

And there you have it. For what comes after, read this book. There is much that we should be grateful to Arunabh Sarkar for.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments