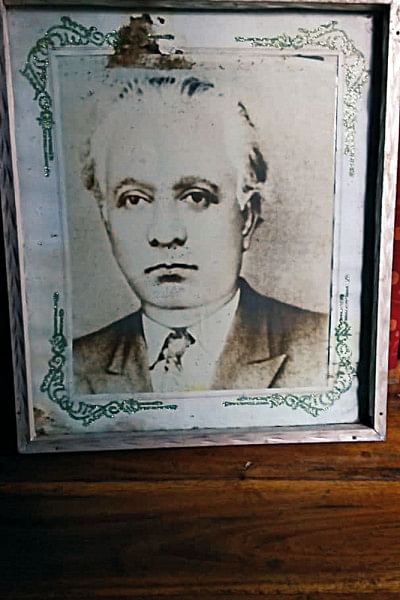

Remembering Abdul Quadir: Life and Anecdotes

Today, 1 June 2019, is the 113th birth anniversary of litterateur Abdul Quadir (1906-84) who was born in the village of Araisidha in Brahmanbaria. As a tribute to him, this essay offers snippets of his life and brings together some relevant anecdotes and reflections, which have literary-historical significance.

In an earlier article titled "Our Debt of Gratitude to Abdul Quadir" (Daily Star, 9 March 2019), I mentioned his substantial contribution in Bangla literary culture. He preserved much of what we hold on to as the Bangla literary canon, including the works of Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (1880-1932), Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899-1976) and other pioneering twentieth-century writers. I emphasised the necessity and ways of showing gratitude to him and other giants of Bangla literature.

During a vacation in March 2017, I had long conversations with some individuals in Araisidha who knew Abdul Quadir well. I was intrigued to learn the historical and religious significance of the village. According to one of my interlocutors, Mughal rulers once stayed in the village for two and half days and it was a place of Hindu siddha purushas (accomplished persons)– which perhaps explains its nomenclature.

Hindu merchants from Araisidha were established in Calcutta, the political and cultural nucleus of British India until the colonisers shifted the capital to Delhi in 1912. Since Calcutta was not exotic to the villagers, Abdul Quadir was able to move there without much difficulty when opportunities arose. In Calcutta, he built rapport with leading writers like Nazrul Islam and developed a literary and journalistic career.

Calcutta, being the centre of literary activities of eminent Bengali (Hindu and Muslim) writers of his time, in 1929 Abdul Quadir went there and began working for Mohammad Nasiruddin's (1888-1994) Saugat (gift) and contributed to other periodicals as well.

He launched a monthly literary magazine Joyti (victorious/glorious) on his own and with his own money. Between 1930 and 1933, he was able to release only thirteen issues, and eventually ceased its publication for lack of funds. He wrote six Joyti editorials titled Shampadaker Panji (Editor's Almanac). Although Calcutta was the place where Abdul Quadir began his writing career, he produced most of his masterpieces after returning to what is now Bangladesh in 1954.

Abdul Quadir's upbringing was rooted in a village society. His father Afsar Uddin was mainly a farmer who was involved in the jute business early in his career, earning him the name Afsar Uddin Bepari ('merchant'). He was a sturdy, able-bodied man who remained physically active and worked in agricultural fields until he reached 100. He died on Tuesday 4 December 1973 aged 110.

Abdul Quadir was the only child from Afsar Uddin's first wife who came from the neighbouring village of Bayek and died of cholera when the poet was only 2 years old. He began his schooling at Bazar Chartola Madrasa, which was moved to Araisidha in 1932 and is now known as Araisidha Kamil Madrasa. Later he studied at Annada High School in Brahmanbaria town and lived in the adjacent village of Bhatpara. Afsar Uddin loaned a healthy cow to the lodging family so that his son had a generous supply of milk.

He passed SSC form Annada with outstanding results before completing intermediate education from Dhaka College with flying colours. While studying at Calcutta University, he established a lifelong friendship with Palli Kabi Jasim Uddin (1903-76).

When Afsar Uddin faced difficulty in financing Abdul Quadir's education, he approached a local Hindu elite to borrow some money. The man was ready to help but with the condition of taking possession of the boy Abdul Quadir in return for financial assistance. Afsar Uddin became furious and left the premises.

Abdul Quadir once talked about his humble economic origins rather humorously, stating: "At 50, Rabindranath Thakur stopped consuming rice and opted for lamb soup. If the son of Afsar Uddin chooses a lifestyle of such gastronomic delicacies, it would force my father to sell off all his property within days."

The title of Abdul Quadir's poetry book Dilruba (1933) was inspired by his first wife, Dilruba Begum of Majhipara in Nabinagar upazila. Three months into their marriage, Dilruba was going back to her natal home in a palki (palanquin). The shabby palki was broken on the way and the traumatised Dilruba died after reaching home on that very night.

Abdul Quadir then married Nargis, daughter of the communist comrade Muzaffar Ahmad (1889-1973). In order to contain anticolonial rebellions, the colonial government aimed "to prevent the early socialist network from becoming politically effective" and intercepted letters between Muzaffar Ahmad and the revolutionary leader M. N. Roy (1887-1954). The former was arguably the prime target of its "anti-Bolshevik surveillance network" in Bengal. Both before and after 1947, the government remained hostile to the Communist movement, forcing Muzaffar Ahmad into hiding. He suffered long, multiple persecutions and imprisonments.

While in prison, Muzaffar Ahmad once said to Nazrul Islam: "I heard that my daughter is now of marriageable age. Find her a groom." Actually, he had been fleeing a British huliya (arrest warrant) and left home when his wife was six-month pregnant with Nargis. As Nazrul Islam then made mention of Abdul Quadir, Muzaffar Ahmad said: "Will he be eager to marry my daughter?" Upon learning this, Abdul Quadir asked Nazrul Islam a comparable question: "Will Muzaffar Ahmad agree to marry off his daughter to me?"

Finally, Abdul Quadir informed Nazrul Islam that he needed to discuss this important matter with his father before proceeding. Eventually, Abdul Quadir along with Nazrul Islam visited Muzaffar Ahmad's family in Sandwip for the solemnization of marriage. It was during this visit that Nazrul Islam wrote a poem entitled "Batayan Pashe Gubak Tarur Saree" (rows of betel-nut trees next to the window), as he was captivated by large groves of betel-nut trees in the island.

Sometime in the mid-1970s, Abdul Quadir visited and gave a speech to the students of Araisidha KB High School. Encouraging female students to excel in education, he mentioned Rokeya as an inspiration and shared with them glimpses from the life of the educationalist and feminist social reformer. While addressing the boys, he said: "A hand that holds the pen should not hold the stick," that is to say, an educated man should not resort to brutal repression or acts of violence.

In Calcutta, at one time when Rokeya was unwell, she sought Abdul Quadir's assistance with some of her writing. He went to see her and addressed her as "Ma" (mother), hoping that would relent her to let him see her face. Rokeya told him lightheartedly that she understood his motive, adding jokingly "Your Ma is very beautiful"; she then let him see her feet only. He narrated this incident to suggest that Rokeya had to maintain strict purdah (the cultural practice of female seclusion) while pursuing literary and educational activities, even though she contested its extremity.

On a final note, researching Abdul Quadir's life has personal resonances for me. He and I have a common academic interest in Rokeya's work. Moreover, discovering him has been a transformative experience, as it involves reconnecting with my roots and strengthens my attachment to my village and its people. Visits to Araisidha in the last years and encounters with people who spent time with Abdul Quadir reinforced my interest in his life and works. Undoubtedly, they have resulted in a significant increase in my appreciation of where I come from and have allowed me to see it through the eyes of my predecessors.

There are certainly great men and women in every corner of Bangladesh to whom we owe the foundation of our literary and cultural life. Commemorating their lives and reading their work can help us regain our cultural confidence and independence and establish our national pride once more. Deciphering their origins and journeying through their writings have pertinent relevance to us and the next generation, as our cultural history is tied to our literary figures.

Note: I am grateful to Abdul Quadir's nephews Abdur Rakib (1943-), Mahbubul Alam (1946-2019), Abdul Baki (1957-) and Sajedul Alam Jilani (1964-) for their readiness to share useful information about the poet-critic. My exchanges with my teacher Mahbubul Alam were especially helpful and enlightening. He passed away on 28 April 2019; I mourn his death and miss his breadth of intellect and humour.

Md. Mahmudul Hasan teaches literature at International Islamic University Malaysia. He previously studied and taught at the Department of English, Dhaka University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments