Looking Back on Kazi Nazrul Islam’s Bisher Banshi

John Milton's Areopagitica (1644) is a fine specimen of the prose polemic defending the freedom of expression and opposing the governmental licensing of publications and procedures of censorship. Milton remonstrated with the Parliament of England about the Licensing Order of 1643 which permitted books to be conveniently proscribed on the grounds that they would have scandalous or seditious or libelous elements. This practice to curtail the freedom of thought descended to the time of the British rule in India when Kazi Nazrul Islam was, through his writings, lambasting the British rule in India. The poet's fearless voice against the British colonialism infuriated the then government which resulted in the banning of his books one after another, and the imprisonment of the poet himself. The British government failed to realize that such attempts to impede knowledge were in fact tantamount to the discouragement of all learning, and would thwart the advent of truth. This essay sheds light on what exactly happened—how the book was banned and again freed—to Bisher Banshi which the government found to have contained elements of "inciting young men to rebellion" and decided to immediately ban it in the year of publication in 1924.

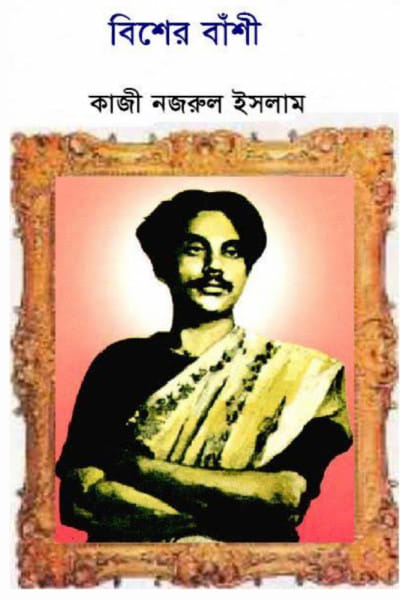

Bisher Banshi is extraordinary in form and content. When first published the book had an impressive and insightful cover designed by Deenesh Ranjan Das, editor of the Kallol, a notable periodical of the time. The cover portrays a boy playing a flute intently. He is encircled by a poisonous snake. The boy is immersed in the perennial melody of the flute. With the mesmerizing pull of the strains the sun rises spreading red ray across the eastern horizon. Stunning in intensity, the 27 poems of the book are marked by the poet's revolutionary zeal, feelings of compassion towards the oppressed and sometimes scorn for the repressive rulers. The Probashi, a contemporary elite newspaper wrote, "The poems of Bisher Banshi are like volcanoes that set the poet's heart ablaze. In this hard time this book will stimulate the oppressed people of the country with fresh pledge and consciousness."

Shishir Kar, author of Nishiddha Nazrul (1983), provides important information about how Bisher Banshi was proscribed. Having examined the government files, records, and notifications he claims that the first person who drew the attention of the Government about the book was Akshay Kumar Duttagupta, the librarian of the then Bengal Library. In September 1924, Mr Duttagupta wrote in a letter to the Police Commissioner that the book "is of a most objectionable nature, the writer reveling in revolutionary sentiments and inciting young men to rebellion and to law breaking…. I recommend that the attention of the special Branch of Criminal Investigation Department may be drawn to this publication." Mr. Tegart, the then Police Commissioner, collected more intelligence reports about the book and passed orders for immediate proscription and seizure of the book. Few days afterwards, A N Moberley, the Chief Secretary, announced the proscription of the book through a government gazette in October 1924 which read, "the Governor of Council hereby declares to be forfeited to His Majesty all copies, wherever found , of a book in Bengali entitled Visher Vanshi printed at the Bani Press , 33A , Matan Mitra lane , Calcutta and published by the author Kazi Nazrul Islam , Hooghly, and all other documents containing the matter of the said book contains words which bring an attempt to hatred or contempt and excite or attempt to excite dissatisfaction towards the government established by law in British India , the publication of which is punishable under Sec,124A , Indian Penal Code."

As the book earned immense popularity with the youngsters, the government faced problems in imposing strict embargo on the book. In those days it was not possible for the printing workers to bind all the books together, many of the printed formats of the books used to lie down the floor of the printing houses; sometimes it was impossible to know how many unbound books remained under the huge heaps of papers in the printing houses. In this connection, Muzaffar Ahmed (1889-1973), pioneer of the communist movement in India is worth quoting. He shares in Kazi Nazrul Islam: Smritikotha (1965), "I was arrested in 1923 in Uttar Pradesh on political reasons, after sporadic visits to some places in India I returned to Calcutta in January, 1926. I saw many youths contact the book binders with utmost enthusiasm for the banned books. There were many book-binders who helped the poet in that serious financial crisis by selling the book in secret; Pranthush Chatterjee of Hooghly was one of them." Though the authority, afterwards, raided probable bookshops and printing houses in the College Street and Cornwallis Street including the poet's house in Hooghly, no book could be traced.

Humayun Kabir (1906-1969), a contemporary educationist, politician and writer, appealed to the government in the Bengal Council to lift the embargo from the book, but didn't get any immediate response. He asked the then Home Minister Mr. Nazim Uddin if the authority had any decision to withdraw the embargo from the banned books considering the ongoing worldwide political instability due to World War II. In March 1939, Nazimuddin informed Humayun Kabir that the government would not take any such decision to lift the order of proscription from Bisher Banshi. Though there was exchange of letters and notes among the government high officials, police officers and officers of the detective branches could not proceed with any positive endeavours. In March 1941, the Home Ministry (department of politics) in an important note finally announced that the government thought it injudicious to withdraw the ban on the books. The original note read: "… Bisher Banshi was proscribed in 1924 and also considered to be seditious. I suggest that it would be inexpedient to remove the ban during the war that there is in any case good ground for retaining it." Therefore, it was clear that the books would not be freed to the reading public during the tumultuous hours of World War II.

In April 1945, after twenty-two years of the book's proscription, the government lifted the embargo from Bisher Banshi in a time when Nazrul fell victim to aphasia and amnesia. The poet has, throughout life, voiced for the disenfranchised and thundered against the evils of the British rule. Bisher Banshi, a poetic testimony of Nazrul's anguished mind, remains as a spirited literary resistance against the unjust governments of all time.

The writer teaches English at University of Chittagong; can be reached at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments