Rethinking Dhaka's Urbanism: A Child's World in a Manmade City

In 1998, at Shangshad Chattar, an infant was relishing fresh air in the country's largest and most emblematic civic-space. Through her growing years, the child enjoyed a park next to her home. But the park was grabbed by local businessmen who turned it into a mega shopping mall. After 18 years, even the chattar, as well as other public sites, shut off access; today, a wall surrounding it ensures a strong barricade.

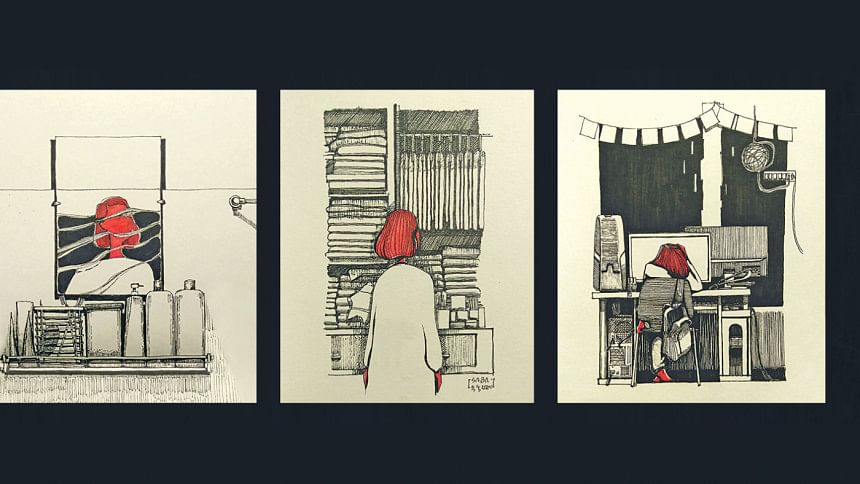

Last month, her strolls down the alley became restricted due to COVID-19 and today, she is depressingly confined by the four corners and restrictive walls of her home where all she can see are a mirror, a television screen and a small window. Her experience of the world seems to have been limited by the interior of her home. It reminds her of Mannah Dey's song: Char deyaler moddhe nanan drishho ke, shajiye niye dekhi bahir bishho ke.

We, Dhakaites, are faced with a violation of our human rights and more importantly of children's rights. The urbanism of Dhaka is being suffocated. This is a more acute problem for the children, for whom open spaces are vital. UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (Article 31) states: "That every child has the right to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts." Ironically, Bangladesh, where these rights of children are being violated openly, was one of the first countries to sign this UN treaty on January 26, 1990. Neither our urban design guidelines nor the architecture of buildings and structures address open play spaces for children, leaving us with an unhealthy claustrophobic environment. This is even more perilous during this time of COVID-19 when cross-ventilation and open air are an unwritten mandate to remain safe (The Germ-Cleaning Power of an Open Window, https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-019-3717-9).

Is Kahn's hope or the child's simple desire and right to play, run and breathe, an illusion only? Is it something beyond our basic rights?

Today, with soaring high-rises, hyper-mobile urbanism, and a burgeoning economy, this is what Dhaka, a megacity of 18 million of the Global South, offers. Those who live in the rural parts of the country or the outskirts, or the minority who own a first or second home in the suburban or the peri-urban areas such as Gazipur, Savar, and Ashulia, or those who can afford to cling on to their bungalows, or bagan baris of the days of the 50s, 60s, or 70s with open spaces around them, are the lucky ones who can breathe. The rest of us from all walks of life, can barely afford to relish moments surrounded by nature with the open sky, chirping birds, or greenery. Dhaka is just another sub-category of what urban theorist Saskia Sassen calls a complex, globalised production network.

As a developing city, Dhaka doesn't only compete with other cities as production nodes but also competes with their imagery for the same postcard perfection. Recently, it has been boasting its beautiful night-time views which echo the image of south-eastern cities such as Singapore, Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur, if not the far western ones like New York or San Diego. But the flashy lights and glamour are just another systemic cover-up of the mess underneath. What it conveniently forgets and hides behind the hubristic vision of urban designers and architects is its landscape which demands to be more democratic.

In contrast to Dhaka, in the cities of the Global North, people have the privilege of enjoying fresh breathable landscape areas – many living within walking distance of open spaces. This is due to Europe and America's response to unplanned urbanisation and industrialisation in the 19th century that resulted in severely polluted and thus morbid urban environments. British planner Ebenezer Howard's Garden City model, where residences have gardens and greenery and ample open space, has been emulated in many ways. Though foundational to America's sprawling, the unsustainable suburbs and the Green Belt cities in the West were based on thoughtful integration of children's spaces and controlled population densities where density and healthy living have been entwined. After more than 100 years of what the West confronted, Dhaka is, unfortunately, facing the same fate. We chased buildings but forgot to see what was around.

There are reasons why we all feel so restless while stuck inside our homes. There is this constant stress about the pandemic and its dire consequences. But another profound reason could be just the fact that the need to be outside is actually in our DNA. If we look back at the history of the modern civilisation, for the majority of our time on this planet we were hunter-gatherers with a deep-rooted everyday connection with nature and the outdoors. The megacities that we live in now may seem overwhelming, but in the context of the bigger picture, we have been living in big cities only for about just one percent of the time of human history. If the entire time we have walked the earth could be squeezed into a year, we would find that we have been living this nature-deprived city-life only for just about four days! No wonder we long for the outdoors like our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Our kids are no different, they are meant to live in nature, not concrete.

Now that we are stuck in our homes, we suddenly realised how valuable spending time outdoors is. But did things really change for our children? Were they used to spending more quality time outdoors before the COVID-19 situation unfolded? Research on school-going Dhaka children's daily life (see study titled "Child-Friendly, Active, Healthy Neighborhoods: Physical Characteristics and Children's Time Outdoors" published by Sage) depicts the alarming truth. Many children in Dhaka do not spend even a minute of free play outside their houses. In that regard, staying inside 24 hours a day is not completely new to them.

Children's dreams are not arbitrary but rather work as design-aid. We, the designers, need to reimagine our urban spaces through their lens, which can easily guide our design and help reclaim their precious, playful childhood spaces of wonder and limitless imagination – thus including their needs in the design agenda. These spaces can be designed, defined and structured and, at the same time, they can be informal or unstructured that unwrap the scope for variable uses.

The lifestyle post-COVID-19 teaches us that even a small garden for private/family gatherings offers healthy time without increasing the risk of community transmission. Some greenery at home offers a space to play, breathe fresh air and most importantly help in the cognitive development and health of children who may be otherwise ruining their valuable childhood on video games and other gadgets. Organic cities like Old Dhaka already exemplify such spaces where the kids play on rooftops or street nodes. From ground to top, there is a flow of children's space, where children can play on rooftops while socially distancing, and socialising in old ways – from one chhad (rooftop) to the other.

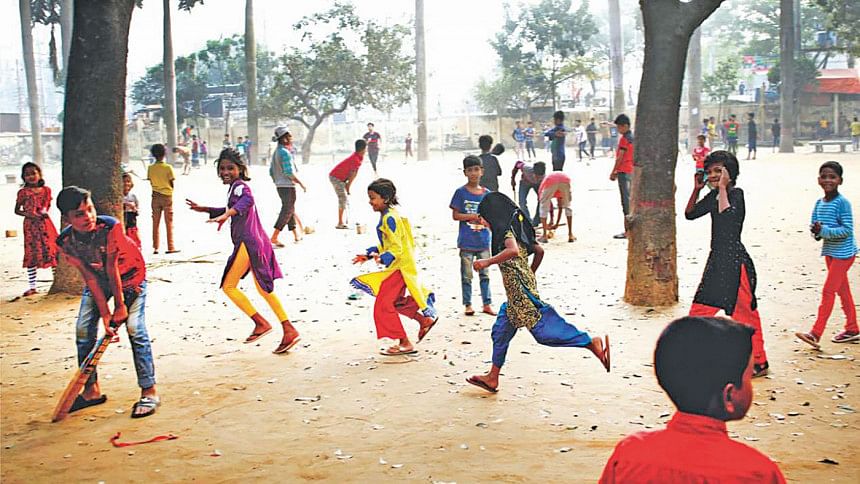

Margaret Crawford called this spontaneity "everyday urbanism" – that is, a space which is meant for walking could be used for playing cricket, informal gathering or more. In Jane Jacobs's words, they are "sidewalk ballet", where individual dancers (children) by collective ensembles reinforce each other and compose an orderly rhythmic urban composition. A sidewalk or chad thus gains a life of its own where children's activities make the space more meaningful and create a deeper association. For instance, Old Dhaka is the locus of cultural heritage such as Sakraine or kite fests, where children come out to play in exuberant spirit. This process of space creation and reclamation generates a deeper association with their community and thus a sense of belonging. With a bit of creative input from designers, the old town model can easily be emulated in new Dhaka's urbanism with altered garden and usable floor spaces at different levels.

The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies stress and low physical activity as two of the leading contributors to premature death in developed nations and developing cities like Dhaka ("Obesity and Overweight", World Health Organization, 2006). What children yearn is what they need; time spent outdoors and contact with nature are associated with multiple developmental domains. It increases physical activity, supports creativity and problem-solving skills, enhances cognitive abilities, improves academic performance, reduces Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) symptoms, enhances nutrition, improves eyesight, improves social relations, reduces stress, and the list just goes on and on. These developmental benefits of nature are not mere hunches, rather scientifically proven facts. Child advocacy expert Richard Louv, in his powerful work about the divide between children and nature ("Last Child in the Woods"), discussed the lack of nature in the lives of today's wired generation. He calls it "nature deficit disorder"— and he points to it as a cause of some of the most disturbing childhood trends, such as the rises in obesity, attention disorders, and depression. At this tipping point of urbanism, we take this deficit of nature and deprivation as part of our normal urban lives. Consequently, children's lives are spent chasing the mythical urban manifestation, which they don't yearn for.

Historically, Dhaka inherited a fit urban legacy from the Mughals, Colonial Raj and, even later, from the East Pakistan era when we had open spaces to a much larger extent than today. The Mughals' baghs and bagans, literally refer to woods and rose gardens respectively; these places along with many open spaces disappeared because of perpetual land-grabbing and imprudent urban planning and design. Even the popular Sangsad Bhaban ground, that was once used by people irrespective of age or class, is not only closed but also partly taken up in the name of development.

Shahid Alim Uddin playground at Dhaka's Lalbagh area in old town is an excellent local case study that exemplifies success and gives us a tinge of hope. Without much financial investment and with a simple intervention, the playground was established under Jol-Sobujer Dhaka, a project taken to reclaim 31 parks and playgrounds by the Dhaka South City Corporation. Since its opening, the park has become a popular destination not just for children, but for people of all ages and sex. For a change, a wide paved walkway surrounding a grassy open playground can be seen. The transparency of the fence of the playground allows park visitors an unobstructed green view. The wide walkway has shaded seating arrangements at regular intervals allowing visitors to rest and surrounded by a variety of species of plants. This simple design intervention has magically changed the lives of the citizens from the surrounding neighbourhoods.

The popularity of the park and the presence of diverse users prove several important points. First, parks are not just fancy amenities for the urban rich; they are much needed by all urban communities regardless of their income and social status to adopt healthy and active living practices. Second, thoughtful design can bring people together and create a sense of place and ownership. This sense of ownership also ensures that the park remains well-maintained and safe. Most importantly, it sets an example and teaches us that with collective efforts of stakeholders and citizens, reclaiming parks is not an impossible task amidst the intense battle for land in Dhaka without thoughts or plans to decentralise the cities.

We may make COVID-19 the scapegoat but neither the pandemic nor the dense urban landscape is the reason behind the current morbid situation. It is actually our nonchalance: the designers, stakeholders, and professionals and the systems that define today's normativity, a life without green but greed. Hunger to create a city that looks fantasy-like and yet fails to offer proper amenities. Designing Dhaka through the lens of children is now indispensable. It is crucial to remember, it is suicidal to design a city that does not allow for children's dreams to grow. They can better live without the societal pressures of coaching centres, private lessons, and meaningless competitions inside fancy buildings. This is also the time for us to realise that a joyful childhood with rest, leisure, play, and recreation is something that we should aim to deliver before the next pandemic breaks out.

Today, the severity of COVID-19 has shaken us to the core. The mental and physical stress and economic instability we are faced with are just reminders that we need to build cities that have nature which can offer healing and therapeutic outlets. Rather than expecting a miraculous reappearance of greenery and parks, the city requires strategic planning, regulations, and more importantly ethical stance from urban designers and other stakeholders. It is time to reclaim children's rights. The City Corporations, the local communities, parents, children, architects, policymakers and both private and public sectors should start incorporating children's spaces as a mandate for design. These interventions can be on a macro or urban Dhaka scale, or a micro scale, that is playgrounds, gardens, roof gardens for residences and mandatory open lands ensured by building guidelines and zoning laws through effective dialogue between all the stakeholders.

The pandemic has resulted in deaths and given rise to a lot of fear. It is threatening to bring the world economy to its knees. Millions have lost their income, and millions more will follow. But it has also brought out the best of humanity. We are helping each other in every possible way. We learned to practice proper hygiene, stay hydrated, and take care of our immune system. We are feeding hungry street dogs who would otherwise starve to death due to the lockdown. We learned to maintain social distancing. We mastered all the internet tools for distance education, work, and socialisation. Many of these best practices will, hopefully, be retained even when the pandemic is finally over. We hope, a profound realisation about the everyday life of our children will also seep in. So let's show our empathy to the childlike world, and only then can we see the ripple effects of goodness, echoing Kahn's words: "Design is not making beauty. Beauty emerges from selection, affinities, integration, love."

Dr Muntazar Monsur is an Asisistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at the Texas Tech University and Nubras Samayeen is a doctoral scholar of Landscape Architecture/Heritage at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments