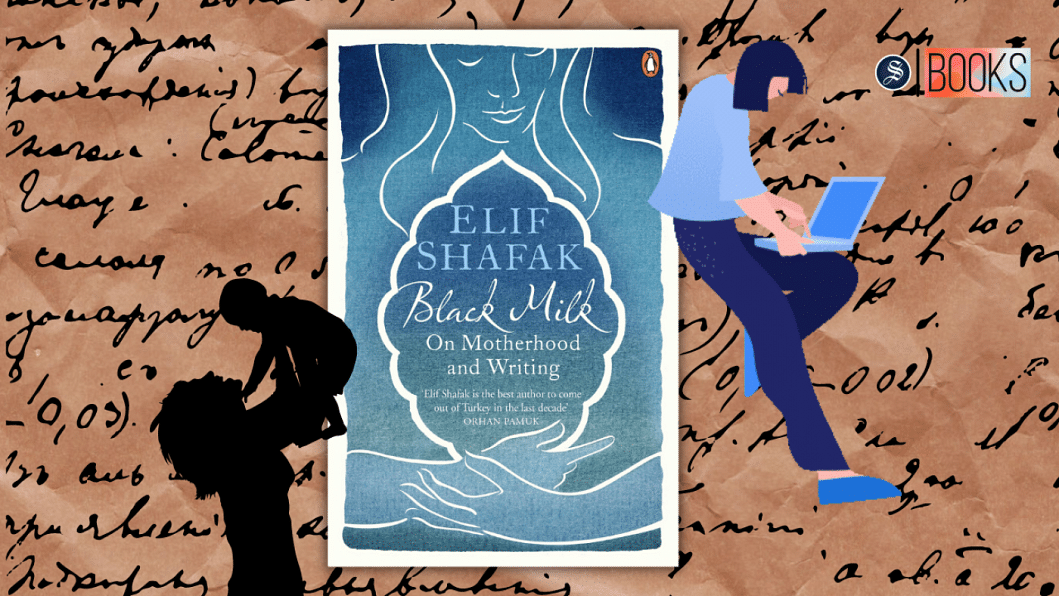

Elif Shafak's 'Black Milk': Can a writer be a mother too?

Standing at the crossroads of motherhood and writing, Elif Shafak writes her memoir, Black Milk (Viking, 2011), as an attempt to create harmony among her multiple and often-conflicting personalities. She writes, "I am a writer. I am a nomad. I am a cosmopolite. I am a lover of Sufism. I am a pacifist. I am a vegetarian and I am a woman, more or less in that order." When this woman, who has diligently mothered volumes of fiction, contemplates finally becoming a mother, she witnesses a coup inside her, a commotion breaking loose among the women in her "harem within".

Black Milk is an autobiographical documentation of Shafak's hesitation, anxiety, perplexity, and self-discovery as she is about to enter the phase of motherhood. Six tiny finger-women, each a part of Elif but each blatantly different from the other, represent six dimensions of her personality. The intellectual Miss Highbrowed Cynic, the go-getter Milady Ambitious Chekhovian, the spiritual Dame Dervish, the rational Little Miss Practical, the motherly Mama Rice Pudding, and the lustful Blue Belle Bovary— all the voices are in constant attempts to shut other and take reign over Elif. Our ambitious writer, author of beloved novels like The Forty Rules of Love and The Island of Missing Trees, and shortlisted for the 2019 Booker Prize for her novel 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in this Strange World, admits to having always favoured the more cerebral characters in her mind over the emotional "womanly" ones. But as the suppressed voices start revolting louder than she can bear, she is forced to listen. She is forced to ask herself if she should become a mother. In the process of eliciting an answer, she questions patriarchy, reminisces about her motherland, Istanbul, and becomes the voice of many women writers.

Shafak pondered over whether all her personalities could coexist. She tried to decipher if it is possible to be a mother despite being an author. In an attempt to solve her dilemma, she resorted to her predecessors—women writers throughout history. Through the lives of Zelda Fitzgerald, with whom Elif's daughter now shares her name, Emily Dickinson, George Eliot, Jane Austen, Emily Bronte, Sylvia Plath and many others, she shows us how likely it was—and still is—for motherhood and authorship to become mutually exclusive.

From this aspect, the book has a flavour of Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own (1929) but with a spin of motherhood on it. In her book-length essay Woolf alludes to the importance of financial security and independence for a woman to emerge as an author. Shafak, on the other hand, recounts how women writers, in times contemporary and past, have chosen to deal, and more often part, with the responsibilities of motherhood to nurture their careers. Virginia Woolf points out the disparate privilege of male writers compared to their women counterparts by making an elaborate inquiry into whether Shakespeare's hypothetical talented sister could have ever made it as successful a writer as he; Woolf walks through this imaginary woman's life to show that she would have never had the same freedom, opportunities, or support, just because of the perceived role of women in society. Shafak poses the same question for the Persian lyric poet Hafiz and his sister.

Black Milk smells of nostalgia and melancholy as Shafak shares parts of her self-imposed exile. As she falls into the hands of a monstrous postpartum depression, the book presents the writer's very personal unrest created by the inner choir of discordant voices. The consequent narrative speaks out the strife of female authorship throughout ages. This memoir reads as a diary of a woman's oscillating allegiance between motherhood and ambition in a world where women are expected to do it all. It is an elegant piece of feminist prose.

Noushin Nuri is studying business in school and literature at home. She can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments