Economy paying the price of cheap funds

The current lending rate, which equals the inflation rate, has brought about major challenges for the economy as a negative interest rate has prompted many large clients to borrow hugely despite subdued demand, giving them the leeway to divert funds to the unproductive sector.

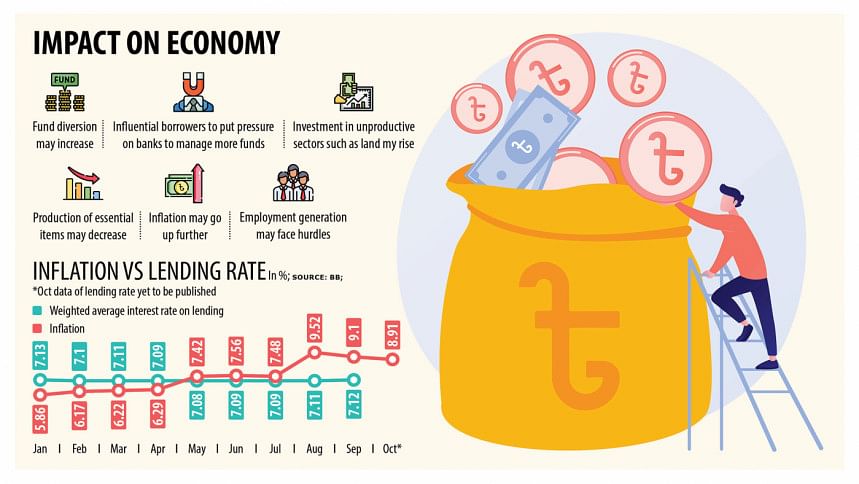

Inflation, driven by higher commodity prices globally, surged to a 10-year high of 9.52 per cent in August and stood at 9.10 per cent in September before falling slightly to 8.91 per cent in October.

The weighted average rate of lending -- which is calculated based on the interest rate of all types of loans offered by banks -- stood at 7.12 per cent in September. This means the real interest rate was negative 1.98 per cent.

"The real cost of funds for borrowers is below zero, which is absurd," said Ahsan H Mansur, executive director of the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh.

The real interest rate for borrowers is determined by excluding the inflation rate from the interest rate. The Bangladesh Bank publishes the weighted average rate of deposits every month. The data for October is yet to be released.

Bangladesh is particularly facing a tough situation as it has kept the lending rate capped at 9 per cent since April 2020, undermining its ability to fight the raging inflation by way of reining in the money supply.

Mansur says that the interest rate on loans may be lower than the inflation rate in an economy for a time being if the market force is allowed to determine the cost of funds.

But the lending rate will supersede the inflation rate within a couple of months in line with the characteristics of any economy, he said.

"But in Bangladesh, policymakers are artificially trying to manage the interest rate. As a result, the financial sector has started to face negative consequences."

The move to support the large borrowers with a lower interest rate has emerged as a bane for savers since banks were compelled to bring down the deposit rate below 6 per cent to ensure a handsome margin as well.

The weighted average rate of savings stood at 4.09 per cent in September, meaning that the real deposit rate was negative 5.01 per cent.

The lending cap is now ignoring the "time value of money (TVM)" as funds have become too cheap, said Mansur, also a former economist of the International Monetary Fund.

TVM is the concept that a sum of money is worth more now than the same sum will be at a future date due to its earnings potential in the interim.

Both borrowers and depositors generally tend to invest in unproductive sectors such as land when an economy faces stagnation.

The price of land in Bangladesh has already gone up, meaning that funds are going to the speculative sector, Mansur said.

If funds are invested heavily in the unproductive sector, the manufacturing of essential goods gets hampered. Under such a situation, inflation rises amid the lower production of essential items.

The outflow of funds from the banking system, alongside banks' need to buy the US dollar in exchange for the taka to settle import bills, has also contributed to the liquidity crunch in the banking sector, crowding out small and medium enterprises.

The central bank has injected more than $5 billion into the banks so far in the current fiscal year, which began in July, after supplying a record $7.62 billion in the last fiscal year.

"The demand for products is low as a large amount of the local currency has gone to the central bank," Mansur said.

"Large borrowers can manage loans using their influence and they invest the fund in the speculative sectors in many cases."

Salehuddin Ahmed, a former governor of the central bank, says employment generation faces a setback when funds are channelled into the unproductive sector.

He blamed the BB for the current situation, saying it is not monitoring the use of funds properly.

The former governor called for the withdrawal of the interest rate cap immediately in the interest of the economy.

"The common people are facing adversities deriving from the high inflation. The lending cap may fuel it further," he said.

Syed Mahbubur Rahman, managing director of Mutual Bank, says that the government has imposed the cap to gear up the productive sector.

"But small entrepreneurs are not getting expected support from banks thanks to the liquidity stress in the banking system. Large borrowers mainly manage funds since they can meet conditions."

Rizwan Rahman, president of the Dhaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry, however, said that raising the interest rate on loans will be harmful to businesses.

"Still, the interest rate on loans should be higher than the inflation rate because we should protect both the economy and businesses. The lending rate cap can be revisited."

The businessman does not support a complete withdrawal of the interest rate cap since banks may hike the rate to 15-16 per cent overnight.

"Then, it will create trouble for businesses," he said.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments