In Search of A Suitable Adaptation

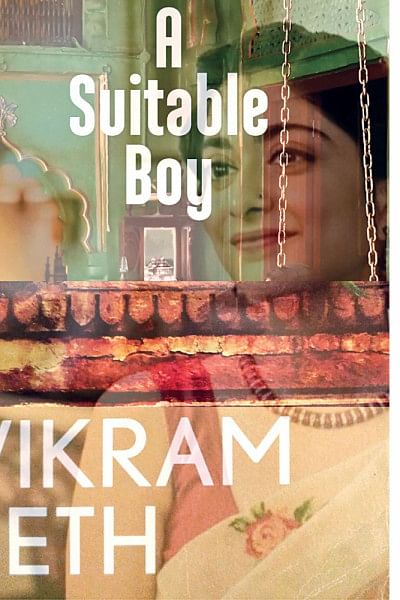

I've long come to accept that there's no such thing as a suitable adaption of a favourite book. Yet, when it was announced that Vikram Seth's A Suitable Boy (1993), a novel I have loved through the decades, was going to be adapted by the BBC for a miniseries—and directed by Mira Nair, no less—I couldn't help but feel hopeful about the possibilities. Could this really be… the one?

A Suitable Boy is centred on the search of an eligible groom for the spirited student of English Literature, Lata Mehra, coming of age in North India in 1951. But it's also the story of a newly independent nation coming to terms with its own identity—a story about communalism, feudalism, land reform, the first Indian general elections and women's position in Indian society—told through the lives and perspectives of four entwined families: the Mehras, Kapoors, Chatterjees, and Khans. Despite being one of the longest books ever to be published in a single volume in English, it is a surprisingly easy read, lucid and engaging in equal measure. What makes the novel a success is the brilliance and playfulness with which Seth weaves layers of stories, depicting the ordinary even in the midst of dramatic familial and political upheaval.

The adaption, alas, reduces it to an almost exoticised story about India, with its monkeys, courtesans, arranged marriages and Hindu-Muslim conflict. The satiric elements evident in the novel are all but lost in the forced attempt(s) to make a larger political point. Perhaps such a fate is inevitable when a 1,488 page novel is stripped to its highlights—the novel is to the adaption what a test match is to a T20—but it's nevertheless disappointing given the extraordinary success of some recent book-to-series adaptions in retaining, even intensifying, the complexity of the text. Why could this not be a longer series, stretched over multiple seasons, so that the characters and story lines could be properly fleshed out?

While some characters, such as Maan Kapoor and Saeeda Bai, shine in their roles—which has perhaps more to do with the actors rather than the screenplay—many others who make the book memorable fall flat.

Lata herself is borderline annoying, with her wide-eyed smile that overpowers every scene and robs the character of its depth. The witty and whimsical Chatterjees—"an intelligent family where everyone thought of everyone else as an idiot"—are reduced to just idiots, and Amit Chatterjee (I was team Amit all the way) to a barely believable contender for Lata's hand in marriage. Many important characters are reduced to mere sidekicks (Praan and Savita, for instance), while others, such as Meenakshi and her lover, are given unnecessary screen time to add some sizzle and spice.

In the novel the dialogues are a revelation—poetic, satiric, always sharp and convincing, but in the series they seem to acquire a saccharine, exaggerated quality. While it makes sense for some of the characters in newly independent India, such as the Chatterjees, to chatter away in British accents, it is beyond any comprehension why Maan does not speak to his Urdu teacher in Urdu or why two villagers are conversing in English. The occasional sprinkling of Urdu/Hindi dialogues (Tabu is magnificent in any language but in Urdu she is to die for) made me wish that the makers had not taken the safe route of setting the show in English simply because it had been adapted from an English novel and/or is catering to an international audience.

Some parts of the series are enjoyable, no doubt. While the cinematography is beautiful and Nair's ability to bring to life the colours, the calmness and the chaos of post-independent India, noteworthy, I, for one, could have lived without the SparkNotes version of this literary masterpiece. I better go brush the dust off my copy of the novel.

Sushmita S Preetha is deputy editor, Op-Ed & Editorial, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments