The dying art of Qasida

"O servants of Allah

We're here to wake you up

Here's the time of blessings

Of Allah; O believers wake up"

This is a loose translation of a melodious Urdu poem that once used to reverberate through the empty lanes of old Dhaka deep into the Ramadan night.

Singing the verses of this Qasida, a form of musical poetry popularised by the Mughal rulers and the Nawabs of Dhaka, Majiul Huq, once a popular Qasida singer, could not hold his tears.

Majiul was in the profession for more than 30 years -- his main job would be to wake the people of his neighbourhood up for sehri throughout the month of Ramadan.

However, over the last few decades, this ancient tradition has disappeared from the streets of Dhaka. Whatever remains in some parts of Dhaka are not genuine Qasida, said some elders who had witnessed and performed this art.

They asserted that Qasida is not just making noise to wake people up, it is much more.

Majiul fondly recounted his memories of when he and his friends used to parade through the streets and lanes of his area during the month of fasting to wake devotees up with poetic songs, urging them to have their sehri on time.

"I started singing Qasida when I was 20. I have seen the art form's heydays. As Qasida singers, we were revered. Nowadays, the practice has ceased to exist as nobody values this tradition anymore."

He said the practice came to complete halt nearly a decade ago.

Mukhles Mian, a disciple of Majiul said, "I can't explain how pure and solemn we would feel in our hearts when we sang a Qasida. Nowadays, people don't need our service. Mosques have loudspeakers to announce the timings and people can get up using alarm clocks in their mobile phones."

He, however, lamented the extinction of a performing art form that combined profound rhythmic verses with devotional singing.

While recalling the glory days, Mukhles sang a Qasida:

"Wake up quick, o believers

Time of Sehri runs fast

We, the Qasida singers

Are humbly doing our task …"

The beauty and appeal of these ancient Urdu-Persian poems, however, are lost in translation.

Others like Majiul and Mukhles said that not so long ago, bands of Qasida singers used to roam most parts of Old Dhaka during Ramadan.

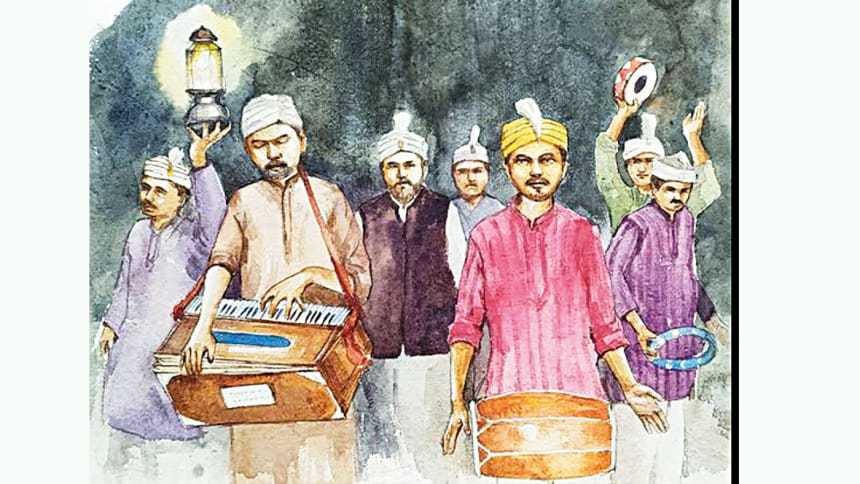

It was common to see a group of singers with traditional musical instruments like harmoniums, little hand drums called dhols and Khartals -- waking people up for sehri with melodious verses. One of the members would be holding a lantern to light up the dark alleys for the travelling band.

Qasida is a Persian word that means praising a loved one through rhyming verses. This Persian word has been derived from the Arabic word Qwasad.

It is an extremely ancient form of Middle-Eastern poetry. Evidence of practising Qasida has been found in Arabic literature centuries before the arrival of Islam in the Arabian Peninsula. Seventh-century Arab historian Ibn Qutaybah wrote in detail about Qasida and the ways of singing it in his book Kitāb al-Shi'r wa Al-shu'arā.

At that time, Qasida would be written and performed not only just in Arabic and Persian, but in many languages spoken by different nations under Islamic cultural influences.

Qasida was first introduced in Dhaka during the Mughal period. As the court language of the Mughal rulers was Persian, Qasidas were written in that language.

When renowned Mughal governor Islam Khan Chisti conquered Bengal and came to Dhaka, he was accompanied by the commander of his naval fleet Mirza Nathan, who elaborately wrote about his experience in Bengal in his book Baharistan i Ghaybi.

In it, Mirza Nathan detailed how Qasidas were introduced in Dhaka and how the early singers would perform them.

We used to perform Qasida only if we were invited by someone or some Panchayat committees. Our uniqueness was that we used to sing Qasida in the old way, without any musical instrument.

The later Mughal administrators of Dhaka, called Naib Nazims, patronised Qasida and its singers. However, by that time, Qasidas gradually became a cultural symbol of the ruling elite and got detached from the ordinary citizens.

During British rule, Qasida regained its popularity among the Dhakaites as the Nawabs of Dhaka patronised it and turned it into a pop culture element of that time.

According to "Dhaka Kosh", a seminal book published by the Asiatic Society on the history of Dhaka, Nawab Ahsan Ullah of Ahsan Manzil used to write Qasidas and was a great patron of Qasida poets and performers.

The Nawabs formed Panchayat committees made up of local elders to oversee some administrative tasks in different parts of Dhaka. These committees used to patronise Qasida bands.

In 1950, when the zamindar system was abolished, most of the Panchayat committees also lost their importance.

However, the heads of these committees, called Sardars, remained very influential in Old Dhaka. They continued to fund and promote Qasida bands, thus sustaining the tradition.

How Qasidas used to be performed

Kashaituli of Old Dhaka was one of the main centres of Qasida culture.

The Panchayat committee of this densely populated part of Old Dhaka is still active and they have a permanent office there. The local elders often sit in the office and recount the golden days.

There, this correspondent met Akeel Ahmed, a 55-year-old resident of the neighbourhood, who said each Qasida band used to have eight to 10 members.

"We used to start singing Qasidas from 2:00am and continued till the start of the Suhoor [Sehri] time. However, preparations for singing started right after midnight."

According to Akeel, three types of Qasidas used to be performed throughout the month of Ramadan.

Those sung in the first 10 days were called Amadi Qasida, those in the second 10 days were called Fazayeli Qasida, and the ones performed during the last 10 days were Rukhsati or Bidayi Qasida.

Akeel and the local elders also said Qasidas were performed beyond the month of Ramadan as well. Every Panchayat office and even influential families used to arrange competitions.

"We used to hold regular Qasida competitions in front of this Panchayat office. The then head of this Panchayat committee Jumman Sardar personally funded the competitions. Qasida performers from different parts of Dhaka used to gather here and compete," Akeel said.

Similar competitions were arranged in Bakshi Bazar, Hussaini Dalan, Sutrapur, Lalkuthi, Urdu Road, Bangshal and other neighbourhoods of Dhaka.

Qasidas were also widely performed in different celebrations such as Milads, Eids and religious conferences.

The verses of Qasida mostly pay tribute to Allah, Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), and renowned figures in Islamic history. Some of the contents are deeply philosophical, which remind devotees about the teachings of the Holy Quran and Hadiths.

Usually, Qasidas are around 60 to 100 verses long but some consist of more than 200 verses.

The style of singing Qasidas used to vary from area to area in Dhaka. In some neighbourhoods, the singers used musical instruments and in others, it was customary to sing without any such accompaniment.

Hussaini Dalan near Nazim Uddin road used to host one of the largest Qasida competitions in its large courtyard. Several bands of Qasida performers permanently resided there.

Sazzad Hussain was the leader of one such band. "We didn't go to other neighbourhoods to wake people up for Sehri, like the other groups of Dhaka.

"We used to perform Qasida only if we were invited by someone or some Panchayat committees. Our uniqueness was that we used to sing Qasida in the old way, without any musical instrument."

Several elders involved with Hussaini Dalan's Panchayat committee confirmed Sazzad's claim. However, the bands would certainly wait for the last 10 days of Ramadan, when the biggest Qasida competition was arranged in the courtyard.

Monowar Hussain, a Qasida singer, explained the rules of the contest.

"A panel of four Islamic scholars or imams used to be the jurists. They used to assess four skills of a singer: the first is Adab-e-Mehfil -- how respectful the singer is about the etiquette and discipline of the competition; Mayar-e-Qalam -- the accuracy of the words of the song; Tarannum -- accuracy of melody, and finally Talabfus -- accuracy of his pronunciations."

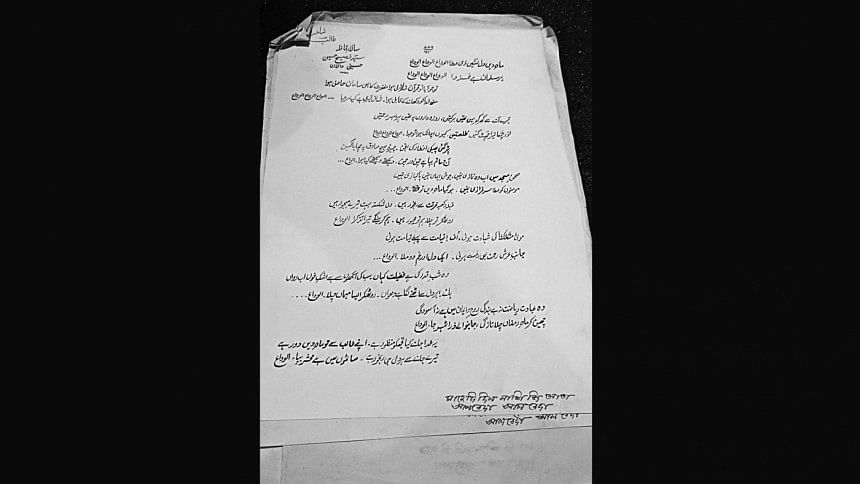

Numerous trophies won by the Qasida bands of Hussaini Dalan can still be seen in the office room there. In one of the almirahs, handwritten manuscripts of Qasidas are preserved with great care and respect.

"These handwritten manuscripts show how perfect and pure the verses are," said Manowar.

The Qasida poets

Although Qasida used to be written in Persian in the Mughal era, during the British and Pakistan period, Qasidas started to be written mostly in Urdu. Many Qasidas have also been written in Bangla.

However, almost all the authors of Qasidas were non-Bangalee and original inhabitants of Old Dhaka, popularly known as Kutti.

The Qasida authors were also known as Kawals.

According to some of the elderly people still involved with practising in their private spaces, the most famous Qasida author during the Pakistan period was Talib Ahmed, a non-Beangalee Qasida singer, who lived in Mohammadpur.

Mustakim Kawal, another resident of Mohammadpur, Ezaz Ahmed, a resident of Bakshi Bazar and Professor Saeedani of Dhaka University's Urdu department, were also some of the famous Qasida poets.

Faruq Hossain, a senior resident of Hussaini Dalan, said, "Talib sahib was the most famous among all Qasida poets. We used to go to Mohammadpur and request him to write Qasidas for us. He was so brilliant that five-six groups would wait at his house all the time for his verses.

"The most amazing feature of Talib sahib's writing was that he could write Qasidas non-stop without repeating words or rhymes. Each of his creations was different from the other. Sometimes he paid a visit to our locality and wrote 20-25 Qasidas in a single day. We paid some money as his honorarium for writing these invaluable poems."

Qasida in Eid processions

Celebratory processions after Eid prayers were also a unique culture of Old Dhaka.

During the Mughal era, Eid processions started from the gate of Nimtoli palace. The starting point was later shifted to Chawk Bazar Mosque.

The procession would go around Chawk Bazar and the nearby neighbourhoods before ending back at the mosque.

Special Qasidas were sung at the processions.

How Qasida became extinct

The senior citizens of Old Dhaka blame the lack of patronisation for this custom's gradual decline.

According to them, the influential families and the sardars who used to patronise Qasida competitions, and the poets and singers are all dead. Their successors, they said, did not feel the necessity to preserve this practice.

The last Qasida competition was arranged in Hussaini Dalan in 2015, they added.

Elders like Jumman Hossain of Kashaituli and Akeel still cherish the memories of reciting and singing Qasidas in competitions as well as for waking up devotees for sehri during Ramadan.

They fear the rich tradition of Dhaka, which is still alive in the minds of some elders, will soon only be found in the pages of history books.

The article has been translated from Bengali to English by Md Shahnawaz Khan Chandan

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments