Should Covid caution supersede learning loss action?

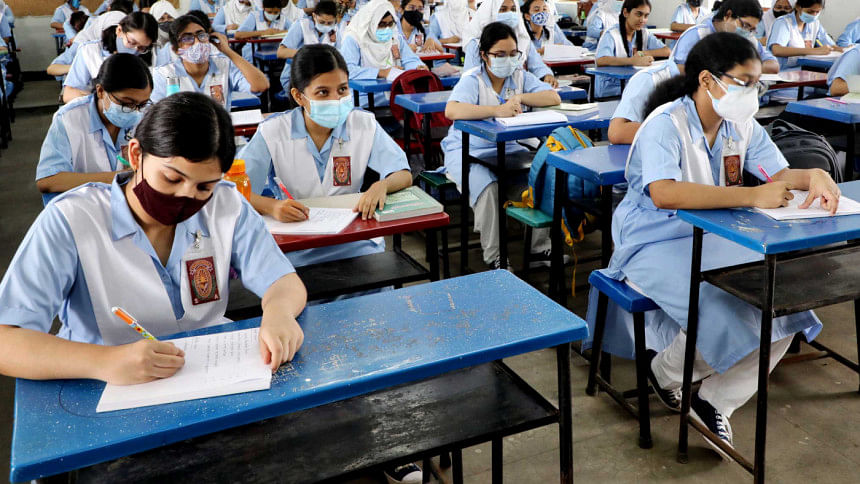

On September 12, 2021, schools in Bangladesh reopened after 18 months of Covid-19 closure—partially, with restrictions. The majority of students, except for Classes 5 and 10 public examinees, came to school one or two days a week for limited hours. At least a quarter of students, many of them girls, did not return. Education Minister Dr Dipu Moni recently warned that if the Omicron wave hit Bangladesh, schools might be closed again. Does Covid caution supersede actions on students' learning loss?

Schools are starting the new year with the usual scramble for admission, and parents' heartache to find a place for their children in their "preferred" schools. Attempts have been made to ease this process by introducing admission by lottery in Dhaka. New textbooks are being distributed all over the country, but without "celebration," as that became a casualty of the pandemic. These are efforts to go back to the normal routine, but do they help address the learning loss challenge?

Bangladesh was one of the few countries that kept schools closed non-stop for over 500 days. Health and education experts argued against the "one size for all" solution irrespective of the infection rates, variation between Dhaka and the rest of the country, and diverse local conditions. Most countries have allowed local decisions by school districts about restrictions and their durations, with overall health and education guidelines provided from the higher administrative levels. Schools received financial and technical support from higher levels, too. It has been argued that, given the problems of bringing the population—including students—within the vaccination net, and the difficulties in preventive measures, testing, isolation and treatment of those who may fall ill, a strict approach was necessary in Bangladesh.

The hard-line approach adopted to keep students safe, however, has been a contrast to actions on helping students catch up and cope with the learning loss. Surveys and studies have documented that most students could not or did not benefit from the distant-mode TV and online lessons, student "assignments," and teacher contacts. It can be reasonably concluded that with a minimal engagement in learning for almost two years, students who were auto-promoted from their previous grade in 2020 were not ready for lessons for the new grade when schools reopened in September. Then, with little regular classroom instruction, they are to be auto-promoted again to the next grade in January 2022. It means that a student who was in Class 3 in March 2020 is in Class 5 in January 2022 without acquiring the foundational skills of literacy and numeracy.

It might be noted that even when schools functioned in pre-Covid days, the majority of Class 5 children did not acquire the grade-level basic competencies in Bangla and maths, as judged by the National Student Assessment. Perhaps the education authorities' logic is—if most children don't learn much when schools operate, it really doesn't matter that they missed 18 months of class.

The Secondary School Certificate (SSC) results, published on December 30, show a 94 percent pass rate and a record number of GPA 5. The exams were held on a shortened content, limited to three optional subjects for the three tracks of humanities, science and commerce. The core subjects of Bangla, English and maths were not on the test. The jubilant students who scored high as well as their teachers said that English and maths were the difficult subjects that brought the scores down. Education experts had advised that even in an abridged exam, the core competencies in Bangla, English, maths and general science should be the main content, because these foundational skills have better predictive value for how students would learn and perform later in education and life.

Earlier in 2021, for the milestone Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) examination, all students were declared to have passed, and were given scores on the basis of the results of their JSC and SSC examinations held two and four years earlier. This was a cavalier approach and undermined the credibility of this important public examination.

Education specialists and concerned civil society bodies have said that, as a response to the unprecedented crisis fraught with uncertainty about its course, an education rescue plan of two-to-three years' duration has to be adopted and acted upon. They advised: carry out a rapid assessment in each school of student readiness for their grade level in basic skills of Bangla and maths (plus science and English at secondary level); extend current school year to next June and help students to be prepared for their grade in core skills (and change school year to September-June permanently); help teachers with guidance, online support and incentives to carry out the remedial work for students; and forego the emphasis on public and school exams and put all effort on teaching-learning to recover the loss.

These practical suggestions are based on the premise that there has been a shock for the education system, even bigger than the one in 1971, when education came to a halt during the Liberation War for a year. This is a bigger shock because schools have remained mostly shuttered for almost two years, and the end of limitations and restrictions is not in sight because the course of the pandemic remains unpredictable. Moreover, the education system is five times larger compared to 1971, making its management that much more complex and difficult.

The authorities have not paid heed to the educationists' advice. The main concern of the decision-makers appears to be to go back to the old routine, regardless of what it means for students' learning outcome. The Directorate of Primary Education has prepared its 2022 calendar retaining the much-disputed Primary Education Completion Examination (PECE), which is planned for November 2022. The secondary education authorities are planning for their public exams in the summer; how students cope with the learning loss is their own business!

The cumulative effect of the prolonged closure and loss—students moving up from grade to grade without acquiring the basic skills and without a rescue and recovery strategy—will harm the students permanently. This generation of students will grow up with a debilitating handicap—unless a remedial plan is put in place. A generational danger in education is looming, which is not receiving the attention of policymakers.

A judicious approach is essential to ensure both student learning and student safety. The education system must survive the present crisis and overcome the adverse generational impact. The educationists' advice to deal with the crisis should be heeded. A rethinking about an education rescue plan and a school calendar to facilitate it is in order, before it is too late.

Dr Manzoor Ahmed is professor emeritus at Brac University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments