The Great Powers Wash Their Hands

Since March 25, when the Pakistani Army was turned loose on a defenseless East Bengal, events have been unrolling which have been described as not less frightful than the war in Vietnam; and the world has glanced that way, at intervals, and looked away again, and done little or nothing.

In any such case it is a puzzle to know where the responsibility for this nothing lies. Ideally, in democratic lands, news agencies report, individuals or bodies alert the public, public opinion is condensed by parliaments, governments take action, or move the United Nations to act. In this case it cannot be said that either information or summons to action have been lacking. Press coverage has been less than it should have been, and intermittent because of frequent crowding out by other events, but there has been enough to give anyone who wanted it a fair glimpse of what was going on. In Britain, The Times (of London) has shown more continuous interest than most other papers. In June the Sunday Times had two full and horrifying reports by two different writers. One of these was told by several Pakistanis on the spot that East Bengal was, going to be cleaned up for good and all, even if 2 million people had to be killed. "This is genocide conducted with amazing casualness," he commented on the cleaning-up process as he watched it. Any nation giving aid to Pakistan was guilty of "financing genocide," wrote the New Statesman on June 5. "It is the greatest massacre since Hitler," wrote the popular Daily Mirror on June 17, asking for a British initiative.

Numerous individuals and groups, in or out of political life, have tried to rouse opinion. In April, Gunnar Myrdal and a group of Swedish writers and scientists appealed to the governments of the five Nordic states to bring the matter before the U.N. In France, there have been a number of strong condemnations of Pakistan, one in June by the Permanent Board of the French Episcopate, one in September by Malraux. In July, a Canadian parliamentary delegation visited East Bengal, and declared that the province ought to be allowed to decide its own destiny. Various similar protests have come from America. Senator Kennedy has distinguished himself; he was in India in August and made an excellent statement, which he followed with a demand for the cutting off of American aid to the murderers "I am distressed," he had been quoted little earlier as saying, "that the Administration finds it easy to whitewash one of the greatest nightmares of modern times."

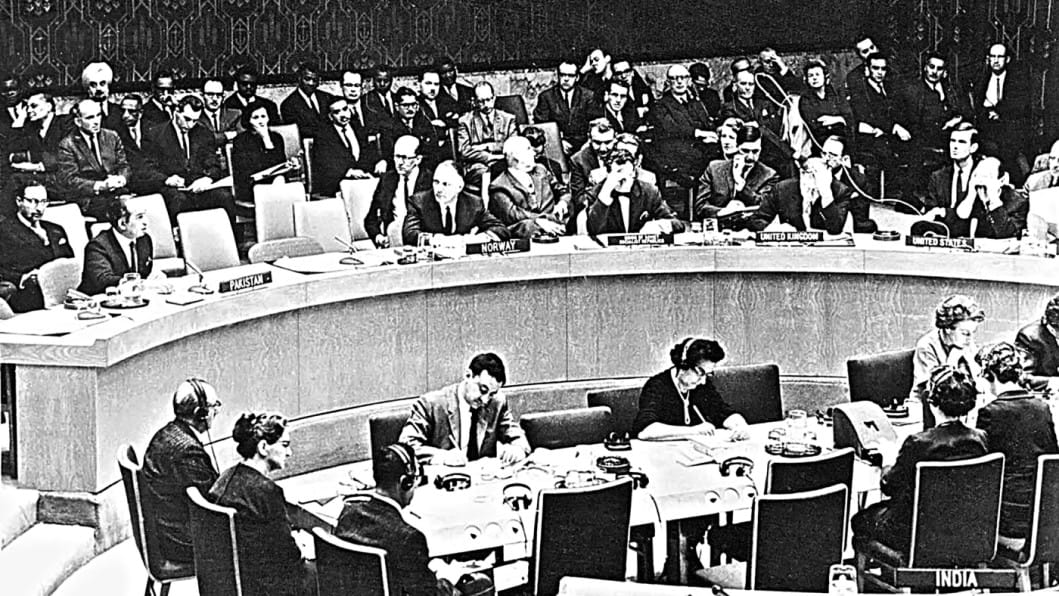

The American and other governments can have been in the dark about the situation only if they were anxious to be in the dark, eagerly ignorant like the public of West Pakistan India has made patient efforts to enlighten them. Mrs. Gandhi appealed for international action on May 26, and since then has made a long series of speeches and statments; she and her foreign minister, Swaran Singh, and her prominent members of her government have visited many capitals. On the other side, Pakistani propaganda has been as crass and crude as was to be expected from regime with the mentality more of a feudal baronage than of modern statesmanship. That has been so most of all in the explanations offered to foreign observers by its spokesman in Bengal. "The attempt by West Pakistan's military government to sell the Western world their side of the story sometimes makes General Westmoreland's credibility gaps look like hairline cracks," one journalist wrote. Yet Western governments went on finding reasons and excuses for inaction, and the United Nations reflected their inertia. Its pundits found a deplorable excuse by saying that the affair belonged to the "domestic jurisdiction" of Pakistan. Not long ago all men claimed a right to beat their wives as part of their domestic jurisdiction, but it is a strange sort of domestic business that turns 10 million people out of their homes and leaves them to be fed by another country.

If ever, as the Guardian wrote on June 14, it was time for the United Nations to rise to the responsibilities entrusted to it, the time was now though that newspaper, like too many others, was still talking of persuading Yahya Khan to "stop his army's butchery," instead of forcing him. Well might Lord Brockway tell a demonstration of supporters of Bangla Desh, or East Bengal, in Trafalgar Square on August 1 that he was "appalled by the inactivity of the great powers and the United Nations." Even charitable assistance to India in its staggering task of keeping 10 million refugees alive was grudging. Mrs. Gandhi had every right to speak with bitterness to her parliament in June of the well-fed world's apathy over the plight of these millions. "If 10,000 refugees go to any European country the whole continent of Europe is afire, with all the newspapers and governments shouting over it." Since then she has had far more, not less, reason for complaint.

All this time India has been on the horns of a whole set of dilemmas. A tremendous strain was put on its resources, just when there seemed, after the victory of the moderate progressives led by Mrs. Gandhi in the general election, a chance of quicker social reform and economic growth. West Bengal, under the weight of its social and economic problems, and with its left-wing parties furiously at odds with one another, has been growing almost ungovernable; for New Delhi to find itself with a shattered East Bengal on its hands as well was an alarming prospect. So was a Communist Bangla Desh under Chinese tutelage. India wanted the refugees off its hands and back in their homes, but they refused to go, and could not honorably be asked to go, until they could return to a homeland free of foreign bayonets. Public anger against Pakistan, and desire for action, have inevitably been strong. But so has been the government's reluctance to face war, which means further crushing expense, besides worse dangers, with no tangible reward. India's painful hesitations over many months are the best answer to Pakistani propaganda about all the trouble having been deliberately brought about by Indian meddling. A stopgap course was pursued by India of giving limited backing to the guerrilla resistance, while appealing with mounting urgency to the civilized world to take the measures it so easily could against Pakistan. The longer civilization looked the other way, the more desperate grew India's predicament.

Most of the West's obvious interests would seem to range it on the side of India and of Bangla Desh. It is in East Bengal that the two staple export commodities of the old dual Pakistan, tea and jute, are grown; and tea has remained a largely British undertaking, as in the days of British rule. It must be presumed that before March 25 the Bengali leaders were counting on Western opinion to prevent the army steamroller from being set in motion; they seem to have thought that America in particular would be well disposed toward an autonomous regime led by the very moderate Mujibur Rahman. Their own political thinking was attuned to the West, and when invasion came they were bewildered by Western inactivity. As a commentator (P. Gill) wrote subsequently, at the outset "the West had an opportunity to support a movement that was both popular and overwhelmingly bourgeois." Here was something the West has searched Asia for in vain; indeed, it has searched so long that it may have abandoned belief in the possibility of such a thing, and decided to put all its money on solid military men instead.

Moreover, the West has skeletons in its own cupboards that make it less inclined to think about Bengali skeletons. Above all, war still drags on in Southeast Asia, and the West is not alone. China has the conquest of Tibet on its record, and Russia the recent occupation of Czechoslovakia. Even India can be taxed with behavior in Nagaland for some years in the past not altogether unlike Pakistan's in Bengal, though on a vastly smaller scale. It was an unlucky coincidence that Ceylon, important as the staging post for Pakistani transport planes and troopships rounding the tip of India, was in the grip of a left-wing rising when the firing began in Bengal, with resulting official panic and severe repression.

As for Britain, the controlled Pakistani press has had a great deal to say about the hurly-burly in Ulster, and some apologists for Pakistan in Britain have echoed its assertion that in Bengal, as in Ulster, action has been taken merely against a few lawbreakers incited by a foreign government. It is a preposterous comparison; there have been far too many deaths in Northern Ireland, but East Bengal has suffered an orgy of bloodshed. Nevertheless, Ulster puts Britain too in the dock, since the imbroglio is the outcome of fifty years of injustice winked at by every British party and ministry in turn; and it has done lamentably much to keep public attention away from Bengal.

Yet Britain ought to feel a special responsibility for what has happened there. To British sins of omission and commission in India was largely due the emergence of Pakistan as an impossible combination of two regions 1,000 miles apart and as different as Sweden from Sicily. Also, many of the dominant groups in West Pakistan, that prevent it from making progress or giving its neighbor any peace, were created by the British to buttress their own power: reactionary landlords, police and army bosses, time-serving bureaucrats. British conservatism is quite capable of taking pride in these fruits of empire, and has always since 1947 had more liking for the police state of Pakistan than for liberal India; and there is a very conservative government in office now. British military men may be supposed to relish the spectacle of a country more or less permanently ruled by the army they trained. Late in September the Air Chief Marshal paid a visit to Pakistan, for no good reason that anyone could learn.

Still, there are other points of view in Britain, an early in May a sense of responsibility seemed to be dawning when nearly 300 MPs of all shades backed a motion urging ministers to work for a cease-fire. There was also some wholesomely stiff language in a debate on June 8 and 9. "How much longer," The Observer had inquire just before the debate, "can Britain and the rest of the world continue to refuse to get the United Nations involve in the situation along the Indo- Pakistan frontier?" But nothing came of it beyond a mild statement by the Foreign Secretary, Sir Alec Dougas-Home - a feudal land lord by origin - that civil rule ought to be restored in East Bengal. A pledge was however given that there would be no fresh aid to Pakistan until progress was shown toward a settlement. That was enough to elicit a formal protest from Pakistan early in July, followed by a threat from Yahya Khan, made in an interview in August, to leave the Commonwealth - from which he ought to have been expelled long since. Meanwhile, a West Pakistan cricket team was allowed to tour England, amid polite applause. The English like to be admired for their tolerance and friendliness, but at least half of this is a bland disregard of anything but their own comforts and amusements. To the man in the street the whole affair has been just one more squabble between India and Pakistan, requiring nothing more from him than a small contribution to charity.

Britain has at least done enough to annoy Yahya Khan, if not enough to inconvenience him; America has not done even that. Swaran Singh was sharply critical in a parliamentary debate on June 28 of the callous continuance of American arms shipments to Pakistan. They went on all the same. On August 5 Alvin Toffler wrote in The New York Times of this "morally repulsive" aid to the aggressor, while "a planetary catastrophe is taking place in Asia." President Nixon took credit to America for its contributions to refugee expenses, but it seems lunatic logic to give guns with one hand to a gang of brigands, and pennies with the other to console their victims. Late in August the President was quoted as expressing "high regard" for Yahya Khan, and finding fault with India.

Washington is automatically less well disposed to Labour government in Britain, however timidly progressive, than to a Conservative, and in the same way one may surmise that it found the result of the last Indian general election unpalatable. Similarly, the Pakistani elections with their threat however remote to "stability," may have induced Washington to look indulgently on anything that would keep the army in the saddle in both West and East. Attracted by cheap labor firmly dragooned by the police America has sunk considerable investments and loan in West Pakistan. These will be at risk if the economy collapses, and hitherto it has depended on foreign loans plus colonial tribute extracted from Eastern Bengal. When Yahya Khan unleashed troops into East Pakistan he had seemingly been convinced by the military clique around him, and very likely convinced the equally ill-informed Nixon, that it would only be a matter of a single swift stroke within a few days all malcontents would be in jail or in the next world, and order and profits would be restored.

All the powers have been taking West Pakistan, as a force in Asia, far too seriously. It was American patronage and arms that allowed this backward, unstable, really insignificant country to swell itself up like the bullfrog in the fable. Chester Bowles, former U.S. Ambassador to India, traced the series of blunders and miscalculations that made America go on bolstering up the Pakistani Army, and warned of the collision between it and India that has now occurred. Often of late years Russia has seemed overanxious to be friends with everyone, too ready to be drawn into an expensive and futile competition with America by giving aid to all types of regimes, whether it was likely to do any good to the cause of progress or not. Aid to unprogressive regimes like Pakistan's, especially in the shape of arms, benefits only the ruling cliques. Politically Russia itself has nothing whatever to gain or lose by being in the good or bad books of Pakistan's gangster government.

On August 9 a new treaty of friendship was signed between Russia and India. America, it was reported, had warned New Delhi formally that if it went to war with Pakistan China would come in, and America would stand by and do nothing. If so, that was a startling threat, meant to scare India into letting Bangla Desh be reconquered even if Chinese intervention might not really be probable. In face of any such threats the treaty could be interpreted as a pledge of protection. "Russia has virtually underwritten Indian defense in the event of an attack by Pakistan," wrote an Indian newspaperman, and this may be true as far as it goes. Most of the twelve articles are in very general terms, but Article 9 provides for immediate consultation on mutual security if either signatory is attacked or threatened with attack. But another view of the treaty is that it signified Russia's anxiety hold India back from taking any irreversible steps toward war. The anxiety is easy to comprehend. Russia is awkwardly placed between China on the one side and America on the other, with the quicksand of the Middle East always on its doorstep. Yet one would have hoped to see the treaty followed by a firm diplomatic offensive against Pakistan. By compelling the United Nations to do its duty, Russia would have gained greatly in moral credit; and by thus isolating Pakistan it would have reduced the danger that militarists might seek to save themselves by provoking war with India. Mrs. Gandhi's visit to Moscow late in September, quickly followed by President Podgorny's to India, encouraged Indians to hope for growing Russian agreement with their belief in the necessity of pressure on Pakistan.

Podgorny had urged Yahya Khan's government as early as April 3 to put an end to "repressive measures and bloodshed in East Pakistan." Chou En-lai, on the contrary, sent a message, which he published--greatly to his own moral discredit--on April 12, assuring the West Pakistanis of his good will, and promising support if the "Indian expansionists" interfered in what was "purely an internal affair of Pakistan." Repression against a black rising in South Africa could of course be described as a purely internal affair, and doubtless would be so described by Chou En-lai if it happened to suit his convenience at the moment.

Since then the Pakistani military clique must have drawn further encouragement from the extraordinary spectacle of President Nixon getting ready to visit Peking. For years the Chinese have made the air ring with wild allegations of collusion between Washington and Moscow; the word is far more appropriate to the aid and comfort that Washington and Peking have both been giving Pakistan. Collusion between China and Pakistan started a long time ago, and momentarily startled Washington; but it soon grew apparent that it was only a maneuver against India; that no Socialist propaganda would be allowed into Pakistani bookshops, and no Communists out of Pakistani jails. All the real advantage of the connection has gone to the reigning Pakistani reactionaries, only the dishonor to China. The plain, simple blockhead sometimes gets the better of the overclever intriguer.

Forty years ago an American statesman spoke of the Japanese Army running amok in China; now a Chinese Government has been applauding a Punjabi army run amok in Bengal. A diehard devotee of Maoism (there are fewer of these on the Left today than there were a few years ago, and in Britain the Bengali issue has been fiercely debated between the small Maoist and the small Trotskyite groups) might have rationalized this by arguing that China, by helping Pakistan to eliminate the educated middle classes of Eastern Bengal was clearing the way for a new movement under Socialist direction. When this emerged, China would privately help it to cut Pakistan's throat. After all, this devil's advocate might have said, a free Bangla Desh under its old half-baked bourgeoisie would be at best on the level of an Indian province, and one has only to look at the Indian half of Bengal to conclude that there would be no great improvement for the masses. But a Communist East Bengal would attract West Bengal to it, break up the Indian Union, and open the way for all kinds of splendid revolutionary developments. Many of these fine prospects have the air of pipe dreams, or of Chinese national interests, real or imaginary, concealed under revolutionary phraseology. A liberated Bangla Desh, dependent on China alone for economic aid, would be for a long time a very poor country, whereas under a leadership able to invite aid from all sides it might well be materially better off, if less purely Socialist.

But the broadest objection to Maoist Machiavellianism is that Socialists cannot afford any longer to ignore ordinary human decency, as they were too often persuaded to do in Stalin's day. Doing or condoning certain evil for the sake of uncertain good is apt to turn out bad bookkeeping. Open endorsement by a Socialist government of a reactionary dictatorship, engaged in bloody suppression of a colonial revolt, cannot be justified by any circumstances. It is a further evil of Maoist diplomacy that it is obliged to go on deceiving its own people, telling them the same lies that the Pakistani people have been told; and all this deception must retard China's own mental and political growth. Socialist countries will have to be far more politically democratic than they are now, before Socialist foreign policies become more healthy.

China apart, the world's reaction to the barbarism in East Bengal has been curiously like its reaction to Fascist aggression in the 1930s, the years of appeasement. Yet today there is no towering Third Reich to be dreaded and appeased; only a stupid little dictator of a povertystricken country with nothing but a supply of cheap, sturdy cannon fodder. It is ironic to reflect that, human affairs being ordered as they are, all this bloodshed and misery and peril has been inflicted on mankind for the benefit of a few hundred men--military bosses, feudal landlords, get-rich-quick businessmen--in a half-medieval corner of Asia. Seldom in history have so many owed so much evil to so few.

V. G. Kiernan was an eminent British historian. During the Bangladesh Liberation War, he was a Professor of modern history at the University of Edinburgh.

The article was first published in a special issue of The Nation on December 27, 1971.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments