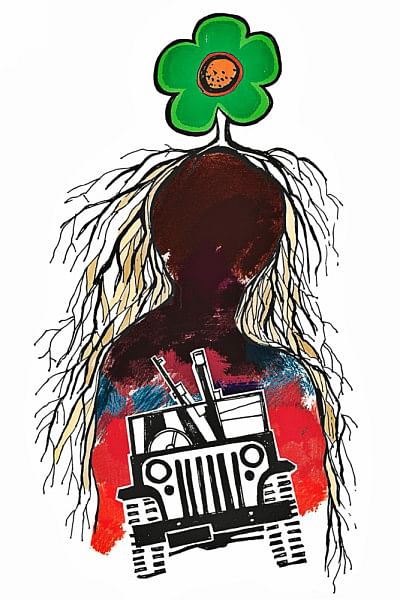

The end of the Liberation War in 1971 was merely the beginning of a chaotic struggle towards a democratic dream. The post-independence period in Bangladesh witnessed a wide array of political actions. With coups and assassinations dominating the political scenario, the late 1970s and 80s witnessed some of the worst battles for political supremacy. The politically unstable period, however, had a silver lining. This was the period that saw the rise of the “band” culture in Bangladesh's music industry. Frustrated with the corrupt political scenario, the artists of the 70s created some of the most powerful socio-political songs in the country's short history.

Writing songs against the establishment was not a new phenomenon. The likes of Kazi Nazrul Islam and Rabindranath Tagore, who wrote poems and songs against the British Empire during the early 19th century, were afresh in the minds of the budding musicians. It was the influence of these traditional poets combined with the Western influence of rock and roll groups that initiated the “rock band” culture in the country. More importantly, these artists set the tone for the rise of the protest music era in Bangladesh.

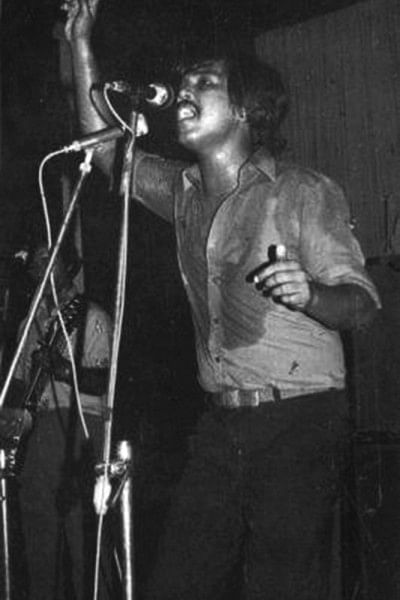

At a time when the world watched Bob Dylan's fight against American apartheid and the Vietnam War, the troubled post-independence era in Bangladesh witnessed the rise of Azam Khan or “Guru”, as he was popularly known. An artist who is credited with having brought rock music to Bangladesh, Khan's straightforward yet piercing lyrics managed to create a kind of fury that had never been seen before.

“The 70s saw a singer with a difference emerge in the music scene, from his tunes to lyrics, hair style and body language, music presentation and use of instrument, everything seemed new to the listeners,” wrote Kazi Hablu, percussionist from the band Renaissance, in an article written dedicated to Khan in 2011.

Khan, along with his band Uchcharon, created songs like “Raillineer oi bostite” and “Ore Saleka, ore Maleka” which described the pitiful conditions of the country. Uchcharon's songs can be best described as a mixture of simple lyrics with a raging inferno of emotions. “Azam Khan sang for the masses throughout his career. If people look into his music, they'll notice his songs are realistic and emotional,” explained Hablu.

It wouldn't be wrong to say that Azam Khan and his songs also laid down the platform for the beginning of band culture in Bangladesh. The importance of Khan is probably best described in Hablu's article, “Band music is extremely popular in the industry today. This is not something, which has been achieved in just a day. Azam Khan paved the way for today's band music with his hard work.”

Khan passed away on June 5 in 2011. Apart from a musician, Khan was also a freedom fighter and fought in the Liberation War of 1971. In his last interview, published in The Daily Star, when he was asked to compare independent Bangladesh to the pre-1971 state, he replied, “I would not have taken part in the war had I known this is how it would turn out. Before independence, Bangladeshi politicians were not corrupt; they were inspiring figures. Pakistanis tried to marginalise us in every way possible. So, the war was inevitable. But is this what we fought for? We had a vision of a state that would uphold the rights of every citizen. Has that happened?”

Uchcharon laid the foundation for the formation of a series of bands by the late 70s. Influenced by the rock culture in the West, bands like Feedback, Souls, Miles, Akhand Brothers, Feelings and Waves created a different kind of sound, which was still new to the country. As time progressed, the band culture gained more impetus and eventually started dominating the music industry.

The beginning of the 1980s witnessed a series of albums and recordings. Souls released its first album in 1982, followed by Miles, which recorded its first-ever compilation in the same year. The 80s also saw bands transcend music beyond the usual genres. For instance, a bunch of musicians from Chittagong and Dhaka combined rock music with a lot of jazz and blues and termed their music “mellow rock”. Renaissance, one of those bands, became popular in the 1980s.

With artists from different musical backgrounds entering the industry, it was only a matter of time before a bunch of “metal-heads” made their presence felt. At the onset of the 1990s, music listeners were taken aback by vicious guitar solos and double-bass drumming. It was a mixture of high-pitched vocals, strong guitar riffs and hard lyrics that created what is known today as “Bengali metal”. Bands like Rock Strata, Warfaze, Winning and In Dhaka found full houses during their concerts in the capital.

A number of these metal songs pointed towards the failing democratic administration of the country. The song Jibondhara by Warfaze, for instance, talks about the way corrupt politicians dictated terms in the country during the 1990s.

Listen to my country's great tale,

Leaders change, yet in the same boat they sail,

Locked inside a life of despair,

Where politicians play games, so unfair,

So many things have happened, yet we're silent,

This will pass we say, this is how its meant,

So many hopes, so many desires,

For this country, we fought against fire,

For freedom, we broke a thousand barriers,

Yet they use the sign of freedom,

To increase their pocket's sum,

Listen to my country's great tale,

Leaders change, yet in the same boat they all sail…”

(Translated by the writer)

The song, released in 1997, was a scathing attack against the corrupt political administration of the country. With a deafening tone and strong riffs, the melody complemented the song's rebellious lyrics. By then, several other bands had expressed their discontent over the country's ruling administration through their songs.

Feedback, Akhand Brothers and Fakir Alamgir followed in the steps of the rock “guru” Azam Khan and penned various socio-political songs. Feedback's album, Bongabdo 1400, released in 1994, which commemorated the 1400th year of the Bengali calendar, comprised songs written by Maqsood Haque, the former vocalist of the band, which charged the government of being a false set-up with unreal promises. The song “Uchchopodostho todonto committee”(High-powered probe committee) criticised committees formed by the government and alleged that the creation of such organisations were merely strategic moves to calm the public.

“Shamajik koshtokathinnyo” (social constipation) was another song in the album that spoke about the everyday problems and social difficulties faced by Bangladeshi communities. “Songs like these were sung at a time when no other musicians dared to do so. These are absolute examples of activism through music during the early and mid 90s. The turbulent evolution of these songs gave our generation issues to think about. These songs asked us...our generation who are in their mid 30s now to be informed and involved citizens of the country,” explains Faizul Tanim, a music journalist who specialises in band music and was also the Country Director of www.amaderGaan.com, a portal for Bangladeshi music.

Haque, however, had his differences with Feedback. He wanted to create the kind of music that would challenge the administration. The other members of Feedback, however, did not share Haque's idea of “activism through music” and thus the band split in 1997 with Haque forming a new band called Maqsood O Dhaka.

With his new band, Haque continued to write songs for the youth on socio-political issues. Their first album “Praptoboyosko nishiddho” (Banned for adults) contained a number of protest songs and became an instant hit amongst the youth of the country. The song “Parawardikar” was aimed at religious fundamentalists and accused them of enforcing their blind belief upon society.

“Giti michil gonotontro” was a musical ballad that mocked the country's democratic administration. In another song “Abar juddhe jete hobe” (We have to go to war again), Haque talks about the need for another Liberation War, this time to liberate the people of Bangladesh from corrupt politicians. He ends the album with an explosive eight-minute long song entitled “Giti bhashon: Mrityudondo”(Musical death sentence) where he demands the closure of the entire political system and then orders a death sentence upon himself, for being a member of the current social environment.

The varying styles of music witnessed during the era of Warfaze, Renaissance and Feedback inspired younger generations and led to the formation of newer bands with a wide array of musical tastes. Heavy metal bands like Artcell and Cryptic Fate burst into the music scene with their own albums, Onno Shomoy and Danob. The 2000s also witnessed the rise of alternative music with bands like Black and Nemesis becoming instant hits in the underground music scene. The arrival of fusion bands like Bangla and Prayer Hall added another dimension to the scene. These bands covered baul songs, which questioned society, and with drums and guitar added a new feel.

Apart from renditions, the 2000s also witnessed artists creating original compositions critical of the political situation. The song “30 bochor por”, by Hyder Husyn, a former member of the band Winning, is a prime example.

What was I supposed to see and what am I witnessing?

What was I supposed to listen and what am I hearing?

What was I supposed to think and what am I thinking?

What was I supposed to say and what am I saying?

After 30 years of independence, freedom is my craving…

“30 bochor por” can be interpreted as a satirical song that mocks the 30-plus years of independence that the country has witnessed. Husyn compares the current scenario to the goals of the Liberation War and ends each paragraph on an ironic note. The song that was released just before the 2007 national emergency became an instant hit amongst the masses.

The baton has since been passed on to the younger bands of the country. While albums by rock bands haven't exactly come out in huge numbers, with the industry's focus steadily shifting more towards electronic music, the likes of Nemesis and Arbovirus have managed to keep up the legacy of their predecessors.

Nemesis's track“ Joyodhoni”, released in 2011, which is about breaking away from a cage and being unstoppable, has gone on to become an anthem among this generation's avant-gardes.

See how they change me,

See how they spoil my life,

See how they to try stop me,

They can't, they have no authority.

The band followed a similar style with their latest album Gonojowar. Arbovirus, in their latest album Bishesh Droshtobbo wrote songs on some of the more recent critical issues such as the building of the Rampal and Roopur plants and the disappearances.

The song “Neelam” from the album, for instance, talks about all the transnational deals through which the country is being “sold”. “Bhenge felo” is a song about how people need to break the “black mirror” and come out on the streets to protest as opposed to using the digital world. “Bondhur laash”, on the other hand, was written with the blogger killings in mind.

While Arbovirus has remained true to its style, their vocalist Sufi Maverick is of the opinion that the number of socio-political songs has decreased over the years.

“Personally I feel that it's difficult for music to act as a vehicle of change because people are more focused on entertainment rather than knowing about what's happening around them. There needs to be more artists focusing on spreading the message and these songs need to be well promoted,” he says.

With the radio and other platforms for promoting music focusing mostly on trending songs, which barely have any socio-political message, getting access to such songs becomes difficult for the general public. Like Sufi indicates, such a scenario can also discourage artists from taking the hardline and merely work with what's trending.

However, at a time when a large number of vital institutions in the country are losing their independence, there's no doubt that the country needs more of these rebel bands.

Follow Naimul Karim @naimonthefield

Comments