An atypical leader

In the fraught political environment of Bangladesh, where the image of politicians and the idea of politics have remained systematically devalued and perverted, Tajuddin Ahmad (TA) dared to be different and charted his journey according to his own intellectual and moral imperatives. This brief essay is a cursory exploration of that contrast, emphasising the ways in which his uniqueness remained in sharp opposition to a political culture marked by rhetorical excess, sentimental superfluities, and the feckless pursuit of self-interest.

First, political leaders usually spend much time and energy relentlessly highlighting their supposed importance with reference to speeches they have made, their nearness to "big" leaders and centres of power, and their participation in intrigues and "king-making" manoeuvrings. They focus on the performative aspects of their public life by emphasising the exercise of charismatic authority rather than ideological consistency or ethical priorities.

Second, political parties abet this process. They do not practise internal democracy or external transparency and are not based on some essential agreement on ideals, values, policies, or a shared sense of history. They represent little more than a clustering of sycophantic enablers around one or two central figures. For most parties, politics is a question of ensuring the supremacy of the leader and transactional bargaining with others. Therefore, they remain in constant flux regarding where they stand and whom they support. They come together in alliances and alignments that are temporary, self-serving, and cynical. Larger parties function as protective covers used by the followers to extract personal gain through corruption, bullying, violence, and maximising the opportunities provided by crony capitalism.

Third, political writing is largely shaped by focusing almost exclusively on individuals. The media become complicit in sustaining this simplistic and personality-centred milieu because concentration on individuals and reporting on speeches is much easier than analysis, judgment, explanation, exposition, or investigation.

Fourth, the notion of "politics" itself is consistently degraded. The idea of politics as a call to public service to achieve some ideals of peace, justice, and progress is reduced to the crass pursuit of power, position, and privilege. Moreover, it lowers our intellectual standards, most noticeably in history and the social sciences, because researchers are intimidated by "political correctness" and the absolute control of narratives by those in power, and because they have so little source material to draw from (except self-serving biographies and memorials). This lack of credible content makes the task of locating empirical evidence, interrogating texts, establishing logical connections, and utilising theoretical frameworks very challenging. Consequently, the writing of history is frequently reduced to sophisticated (and often biased) storytelling. The yawning emptiness in scholarly writings on our valiant struggles, including our War of Liberation, testifies to these limitations.

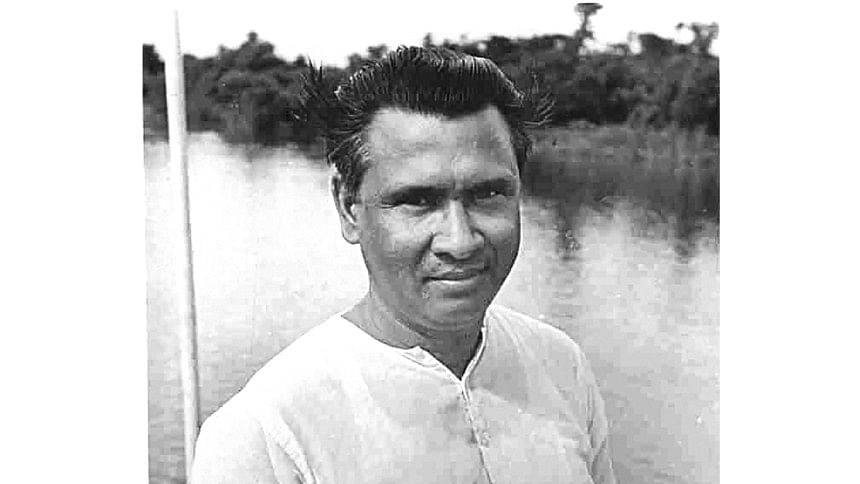

It is in this clumsy and intellectually vacuous landscape, contrived by our leaders and perpetuated by a compliant system, that Tajuddin Ahmad stands out so starkly—determined, defiant, distinct. His claim to uniqueness becomes obvious in various ways.

First, he was a brilliant student. This was noted early and rewarded with many stipends and scholarships. Even though he came from a conservative Muslim family, he was encouraged to attend the best schools, even though they were organised by missionaries (first St Nicholas in Kaliganj and later St Gregory's in Dhaka). He "stood" 12th in his Matriculation exams in 1944 in undivided Bengal and 4th in his Intermediate in 1948.

He decisively disproved the standard middle-class axiom that "good" students do not "do" politics but go into the professions. Thus, as a high school student, he joined the progressive Bongiyo Muslim League in 1943 and served as a councillor in its Delhi conventions in 1945 and 1947. His university education was interrupted by his political activism after the turbulent creation of Pakistan in 1947, but, though delayed, he received his B.A. Honours in Economics, and later his law degree from Dhaka University, while he remained incarcerated in 1964.

Second, unlike many of his political peers and contemporaries who adjusted their sails according to prevailing winds, he remained steadfast in his convictions and commitments. For example, despite his religious upbringing and his own strong faith in Islam (he was a Quran-e-Hafez), he stayed an avowed and unwavering secularist all his life.

Similarly, he never betrayed his liberal-humanist and enlightenment orientations. These evolved over the years and were buffeted by circumstances, but he remained faithful to their inherent values and instincts. He was at the forefront of the Gono Azadi League, a decidedly left-wing splinter within the Muslim League in the late 1940s (the other members of this group were Oli Ahad and Mohammad Toaha, both known for their pronounced leftist orientations), and was one of the key founders of the Awami League in 1949 as a bulwark against the Muslim League's factional in-fighting, authoritarian tendencies, and cultural callousness. In 1951, he was elected to the University Language Action Committee and played a critical role in the mass uprising.

It should also be pointed out that the early trends towards democratic socialism in independent Bangladesh, reflected in the first Planning Commission which he chaired as Minister of Finance and Planning, came largely through his vision, energy, and advocacy. Most of the luminaries in the Committee (Profs Nurul Islam, Rehman Sobhan, Anisur Rahman, Muzaffar Ahmed, etc.) acknowledged his leadership, his intellectual acumen, and his principled engagement in steering that populist aspiration towards fulfilment. It failed; it was overcome by reactionary forces and adverse international circumstances; he was forced to resign, but he did not abandon his beliefs or his party, nor forsake his long and trusted relationship with Bangabandhu.

Third, while it is unusual in a politician—and almost an anathema in Bangladesh—he was self-effacing and humble. This was reflected in his oratorical practices and habits. Instead of delivering firebrand speeches full of admonishments, ultimatums, and demands, he always remained organised, prepared, thoughtful, and almost professorial in his public pronouncements. Substantive relevance was much more important to him than rabble-rousing demagoguery. Moreover, he was a practical leader, more focused on what needed to be done, and how to achieve results, than delivering facile platitudes or participating in ego-driven spectacles.

That same low-key approach was demonstrated when he bravely crossed over to India after Operation Searchlight was unleashed on Bengalis and immediately understood the importance of harnessing India's help in achieving Bangladesh's independence. He, along with his friend Barrister Amirul Islam, met with Indira Gandhi in Delhi on 4 April and was able to persuade her to open the border for refugees and provide necessary logistical support for the liberation struggle. Even a hardened politician like Mrs Gandhi—herself a product of Santiniketan and Oxford—and seasoned public servants like P.N. Haksar found him credible, his argument compelling, and his immediate and long-term plans worthy of respect and support.

In undertaking the momentous task of putting together the Bangladesh government-in-exile and physically picking up Awami League leaders from various places to organise a Cabinet, he retained his down-to-earth demeanour. He played a consequential role in the war as the first Prime Minister of the country and realised the significance not only of the military struggle but also of organising a civil administration that could provide some institutional structure and moral authority to that strategic objective. It is noteworthy that during the entire 9-month struggle, he never lived with his family and, in solidarity with his suffering countrymen, resided in one small and relatively bare room next to his office in the government-in-exile premises in Kolkata.

In none of this—and even after his return to independent Bangladesh—did the people see any chest-thumping braggadocio or self-promotion. When Bangabandhu returned on 10 January from Pakistan, TA immediately went into the less glamorous task of tending to the economy and nudging it towards a populist direction.

Finally, very few leaders demonstrated an awareness of history as keenly as he did. This was amply exhibited in the meticulous and objective notes and diaries that he left behind. In fact, Badruddin Umar's magisterial History of the Language Movement depended largely on TA's private chronicles of the period. Similarly, the highly regarded and authoritative version of the events in 1971 contained in Muyeedul Hasan's Muldhara 71 also relied on his notes and used them extensively. In fact, in the Appendix, which contains many relevant documents of the war, he included many pages of his minutes, memoranda, official orders, and transcripts of meetings written in TA's orderly and precise style, both in English and Bangla. TA's diaries offer a virtual goldmine of information as well as impartial insights and astute observations.

TA was shot to death in a jail cell, together with several fellow Awami League stalwarts, on 3 November 1975. It was a brutal and shameful moment in our history. They may have killed him, but he remains etched in our memories for his lively intellect, his personal probity, his moral clarity, his political integrity and constancy, his populist commitments, his organisational and bureaucratic skills, his contribution to the construction of history, his understated personality, his devotion to his family, and his authentic patriotism. He survives as an example and inspiration and, most importantly, as a defiant challenge to the popular stereotypes and judgements about politics and politicians in the country.

Dr Ahrar Ahmad is Professor Emeritus at Black Hills State University in the US.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments