In the land of pandas and hand-rolled noodles

A fading yellow line separates the growing throng of people behind me from entry into the People's Republic of China. In front, a screen on a machine beckons me to step forward and place my passport on the scanner. Two seconds later, the machine barks at me in robotic Bangla—"Apnar paach angul prodorshan korun abong doya kore shamne takan". While my biometrics are entered into the system, a camera ominously flashes a red light at my face.

What follows the biometric clearance is an hour-long shuffle across an immigration line that rivals Bangladesh's in every way, as stony faced immigration police ponder over passports and take a second round of biometric scans just to make sure you are who you say you are, approximately 20 feet from where you first made claims to your fingers and your face.

As dreary as the immigration process is, exiting Chengdu Shuangliu International Airport instantly puts a smile on your face. An obelisk at the centre of the parking lot reminds newcomers of Chengdu's specialty—here be giant pandas.

There's a weird rule in China that binds corporations to it—they have tofind the best possible accommodation for guests, especially if they've been invited by the government. Something about putting forward the best possible image of the country. I had been invited to cover the Asia Pacific Innovation Day 2019 event, organised by global technology giant Huawei—the largest privately-owned entity in China. For the event, they lodged foreign journalists at the Waldorf Astoria Chengdu, a tower of glass and steel and lavish luxury that sits at a stark contrast with the history of the region.

There is an abundance of history, to say the least. Chengdu, the capital of the Sichuan province, sits on a valley surrounded by towering mountains that stretch across the breadth of Asia—west towards Nepal and Kazakhstan and north towards Mongolia. Chengdu has seen human inhabitation for nearly 4,000 years, and thrived under the Xia, Shang and Zhou dynasties before finally being unified under the Qin dynasty. In the modern era, Chengdu saw rapid militarisation during World War II, with the defending armies having to move westward in the face of the invading Japanese—that militarisation sustained, and the region has served as the Western Theatre Command for the People's Liberation Army since the 1960s. Currently, Chengdu boasts a thriving economy that acts as a bridge between East and West—home to China's information, military, and agricultural powerhouses. It's a city that merges decidedly modern skyscrapers, towering hotels, business centres and large-scale infrastructure like flyovers and sky-trains with ancient single-story wooden tea-houses across a sprawling landscape that never seems to end.

The city itself was never even meant to be this large. With no major river originally flowing through it, Chengdu lacked the lifeline of every major city for most of its humble beginnings. Around 256 BC (during the Zhou dynasty), the Qin state saw a feat of engineering divert an entire river—the Minjing—towards the Chengdu plains, where the city currently stands. Called the Dujiangyan Irrigation System, it's the world's oldest surviving irrigation system—built across Mount Qingcheng through a repeated process of heating up and cooling the rocks of the mountain. A network of bridges with a divider foundation shaped like a fish mouth split the river into two, and after eight years of continuous work, a 66-feet wide channel was created, effectively splitting the mountain into two and bringing the life-force of humans and crops to the region.

For a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Dujiangyan is incredibly accessible. With sprawling walkways, food stalls, information centres and various temples and ancient structures to explore, it's easy to spend hour upon hour here. Bowls of steamed dumplings, spicy hot sausages, and cups of aroma-filled green tea goes a long way in warming your soul after doing a full round of the ancient irrigation system—which tends to frequently get wet from the incredible spray thrown up, not to mention the naturally wet weather of the region.

Communication, despite the Great Firewall of China, is fairly easy if you plan ahead and install WeChat, an app the Chinese use for everything from messaging to map-searching to translating. Otherwise, install a VPN, although there's no guarantee it'll work.

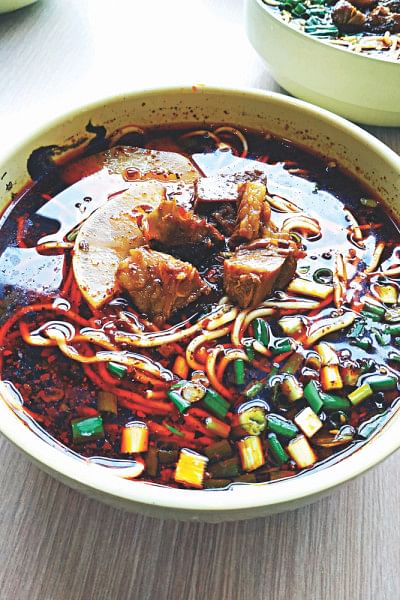

UNESCO might have recognised the importance of Dujiangyan for keeping Chengdu alive and thriving, but their recognition of the city as the "City of Gastronomy" is perhaps more relevant to people wanting to try out China. With an incredible array of culinary experiences on offer, Chengdu is truly deserving of the title. Mostly spurred on by the Sichuan pepper and the love for red meat and noodles, it's probably the most accessible part of Sichuanese culture.

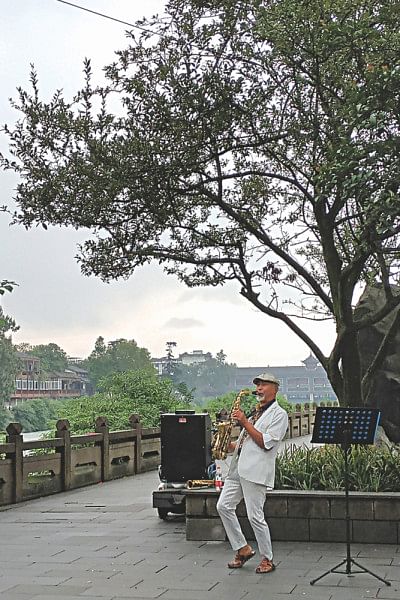

Jinli Street confirms this. As I walk in, I'm distinctly aware of the sheer variety on offer. Lined by two rows of any century-old structures—everything from original tea-houses to repurposed bath-houses and residences—it's easy to separate from the crowd and immerse yourself in the experience of eating out in an ancient street. Wherever you turn, you're guaranteed the authentic Sichuanese cuisine, everything from Dan Dan Noodles (fermented vegetables, sweet bean sauce, bok choy and seasoned meat on top of hand-rolled noodles), juicy and plump wontons in chili oil, cured chicken slices dunked in chili oil, shredded lamb and peppers, fish broths, scallops, mind-bending beef noodle soups—if you love eating, you'll want to keep coming back. Sichuanese hotpot is world famous and a staple diet, so finding a good hotpot place to indulge yourself to a meal of kings is as easy as actually eating it. A word of warning though—the word "spicy" means a very different thing in Chengdu. It doesn't stand for light, at the very least—you'll have tears streaming down your face and your upper lip will be numb and quivering for at least a couple of hours after you're done.

The food has to share the limelight with Chengdu's (and Sichuan's) biggest hero, however. It's said the giant panda didn't get much recognition globally before one was shipped off to Los Angeles in the 1920s and displayed at the zoo. An icon of global conservation (thanks to the WWF logo) and environmental activism, Sichuan is the natural home of the panda. Recent years have seen a huge effort in keeping these picky bamboo eaters alive, and the Giant Panda Breeding Research Centre just outside of Chengdu is a must-visit to see these majestically inept creatures in action. Housed in giant enclosures with plenty of bamboo scattered about for continuous consumption (pandas really do eat all day), the place sees more Chinese tourists than foreign ones. Chinese pride in their national symbol means you'll have to fight for every square inch of space on the thin walkway built across their habitats—which explains why I don't have a single picture of the pandas. It's okay though—seeing a panda stumble out of a tree and waddle across to a platform to fall asleep in the middle of chewing bamboo is a life changing experience, photos or no. As is seeing a panda baby slumped on another inside an incubator, tiny paws occasionally stirring in deep sleep.

It's difficult to ignore China's treatment of the Uyghur, their incredibly pervasive surveillance and social engineering, their suppression of dissent in Hong Kong and Tibet, as well as their militaristic aggression in dominating the regions around their borders. In light of their political atrocities, Chengdu's motto of "A city you never want to leave" seems eerily like a threat. After having experienced it, there might be a modicum of truth in it.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments