Ijere - The death of a god

Like humans, gods too die. Gods are not immortal. They do not die as frequently as humans do but they die after all—in centuries. Through the ages, thousands of gods have died or rather been forgotten. A god dies when there is no worshipper because the relevance of any god is sustained by the number of devotees.

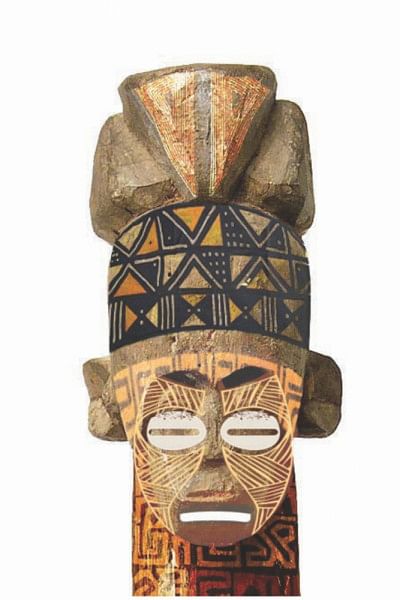

Ijere, a powerful and benevolent god of my ancestors, has joined the list of dead gods. I met Ijere when I was a teenager in the 1990s. Back then, there was a minority of Ijere adherents. Last month when I went to Onu Ijere, the god's shrine, and I was shocked to see that there was no more Ijere. The shrine was overtaken by a lush tree and grasses. An eerie atmosphere pervaded the habitat. The artefacts and the usual fresh animal blood had gone.

I come from Nsukka in eastern Nigeria. My village, Ikeagwu, is about seven kilometres away from the prestigious University of Nigeria, the first indigenous university in the country that was established when Nigeria gained independence from Britain in 1960. My hilly village gives a panoramic view of Nsukka town. When I was growing up in the village, a lot of educated locals and foreigners used to come to the village. I helped in building a party house—made of dry grass—in the mountain where they used to have parties on the weekends. Students of the university also used to organise their own party. As children, we were exposed to city-like lifestyle, yet our village retained its rural dignity.

Ijere was the original god of the progenitor of my clan, Ezema Ugwu. He migrated from a faraway community and settled in Isi-IyiIsiakpu in Nsukka. He had five sons whose offerings made up the five sub-clans of Umu Ezema Ugwu, the children of the progenitor. My ancestor and his five sons faced prosecution from those who did not welcome their settlement. Ijere played a pivotal role in their survival because they went to wars in the name of Ijere and they conquered.

I do not know how they created or found Ijere but my clan was the custodian of the god. Other clans worshipped Ijere but the chief priest had to come from my clan. The chief priest was usually the oldest male but he could delegate to another energetic younger person to perform the sacrifices and ministered to the god.

In my ancestor's cosmology, Ijere was a messenger of Chi Ukwu, the almighty god that created the universe. They worshipped the almighty god through Ijere because humans could not possibly approach the universal god directly. Therefore, they prayed and asked Ijere to intercede for them. They prayed to Ijere for bountiful harvest and protection against their enemies. They asked Ijere for good health and happiness. They prayed to Ijere for plenty of children as well as pray for the survival of their children. The benevolent Ijere granted their prayers and they flourished.

In appreciation of answered prayers, my forefathers often made animal sacrifice to Ijere. They also made a sacrifice in anticipation that Ijere would grant their wishes. As a teenager, I witnessed the many sacrifices made to Ijere. The chief priest would pray to Ijere to accept the sacrifice before slitting the throat of a goat or a fowl. After the blood was emptied at the shrine, we were given the carcass. Right there at Ijere's mountain, we roasted and ate the meat with the chief priest and everyone around.

Eating meats that were sacrificed to Ijere was an unforgivable sin in my Christian home. My Christian parents forbade us from mingling with idol worshippers, let alone accepting meat from them. Ijere upholders were called idol worshippers, pagans and heathens. In catechism, we were told that we would go to hellfire by associating with pagans. Despite the threat of hellfire, childhood curiosity and stubbornness led me to witness the sacrifice made to Ijere. It was a secret I kept from my parents.

When the Christian missionaries came, they told my grandfather's generation that Ijere was a small and evil god. My grandfather did not accept Christianity, likewise the majority of his peers. Unfortunately, he died before I was born. Christian proselytisation became highly successful during my father's generation and Ijere began to lose believers in drove. My parents were forced to adopt Christian names because their indigenous names were not holy enough for Catholic baptism. By my teenage years, very few people were worshipping Ijere. Right now, nobody worships Ijere and the god does not appear to exist.

I am not under the illusion that Ijere worship can be revived. The art of worshipping Ijere is gone forever. We have moved on with Christianity. But Ijere was part of my history and should not be forgotten. Whenever I mention the god, my people become hostile and think that I should not say anything about an evil and impotent god. This perception is an outcome of the demonisation of the god. Ijere was not evil anyway. The Christian missionaries maligned Ijere as an evil god in order to market their own god.

In a mad rush to embrace Christianity, we destroyed our heritage without preserving any of it. Tears welled up in my eyes when I walked around my village, looking to take pictures of heritage sites. There was not a single one anymore. I could not see any artefact. While there are new mansions all over the village, the things that point to our genealogy have been destroyed.

I have often argued that recognising Ijere does not diminish the gods we worship now. It rather gives us a picture of how our culture evolved over time. It means we can take our children to the village and show them how our ancestors worshipped their god. We have inadvertently denied our children this opportunity and they may not forgive us when they realise our folly.

Regrettably, there is nothing left to salvage or preserve. The artefacts have either been looted or destroyed. My task now is to keep the memory of my encounter with Ijere and tell anybody who cares to listen or read that Ijere was not an evil god. Ijere answered the prayers of my ancestors and provided justice. As a teenager, I wanted to ask my dad why his priest would have all the foods and animals they presented for Thanksgiving in the church while there were a lot of hungry congregants. The chief priest of Ijere would never do that because we all ate the meat equally.

I have offered to become the chief priest of Ijere but I know this will not happen because the position is reserved for the oldest in my clan. Besides, Ijere is no longer alive. Anyway, I am impressed by the ethos of Ijere. While the priests of our modern religions buy private aeroplanes at the expense of their malnourished congregants, the priest of Ijere would never do that because any Thanksgiving for Ijere was a thanksgiving for all.

I am really fascinated by how gods are founded or created by a people. Through the ages, humans have created thousands of gods that they worshipped, many of whom survived centuries. But many of those gods could not withstand the competition from other gods. From childhood, I have wondered whether Ijere had the powers ascribed to it by my ancestors. I am often tempted to believe that the powers of the god were imaginary, just like others. There is no proof.

My interest in Ijere was the role the god played in the lives of my forefathers, whether real or imaginary. Religion still matters, at least it gives succour to the people. It gives people the meaning of life. Humans cannot really live without believing in something. For centuries, humans pitifully searched for powerful gods to worship. I am glad that my ancestors created or found theirs.

Chikezie Omeje is a journalist, based in Nigeria's capital, Abuja. His Twitter handle is @KezieOmeje

Comments