QUIRKY SCIENCE

Neutralising Zika

As Zika spreads throughout the world, the call for rapid development of therapeutics to treat Zika rings loud and clear. Taking a step further in identifying a possible therapeutic candidate, a team of researchers at Duke-NUS Medical School (Duke-NUS), in collaboration with scientists from the University of North Carolina, have discovered the mechanism by which C10, a human antibody previously identified to react with the Dengue virus, prevents Zika infection at a cellular level.

Previously, C10 was identified as one of the most potent antibodies able to neutralise Zika infection. Now, Associate Prof Lok Shee-Mei and her team at the Emerging Infectious Disease Programme of Duke-NUS have taken it one step further by determining how C10 is able to prevent Zika infection.

To infect a cell, virus particles usually undergo two main steps, docking and fusion, which are also common targets for disruption when developing viral therapeutics. During docking, the virus particle identifies specific sites on the cell and binds to them. With Zika infection, docking then initiates the cell to take the virus in via an endosome -- a separate compartment within the cell body. Proteins within the virus coat undergo structural changes to fuse with the membrane of the endosome, thereby releasing the virus genome into the cell, and completing the fusion step of infection.

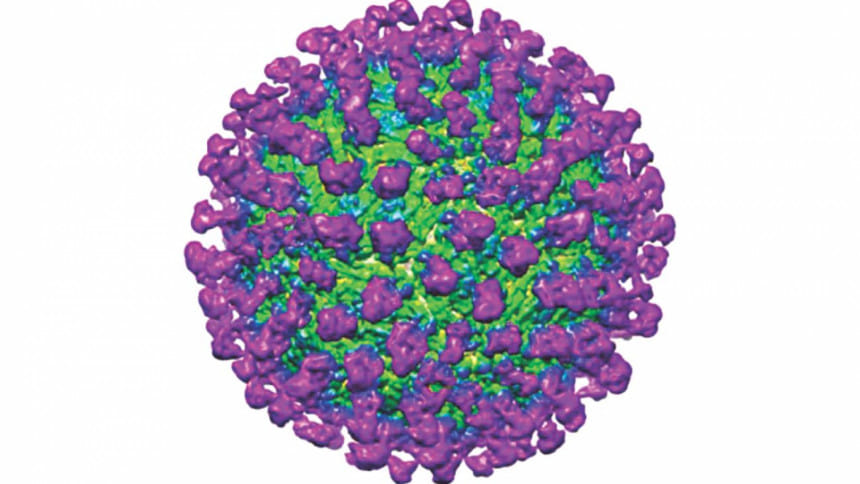

Using a method called cryoelectron microscopy, which allows for the visualisation of extremely small particles and their interactions, the team visualised C10 interacting with the Zika virus under different pHs, so as to mimic the different environments both the antibody and virus will find themselves in throughout infection. They showed that C10 binds to the main protein that makes up the Zika virus coat, regardless of pH, and locks these proteins into place, preventing the structural changes required for the fusion step of infection. Without fusion of the virus to the endosome, viral DNA is prevented from entering the cell, and infection is thwarted.

Immunity in Monkeys

The richest and poorest Americans differ in life expectancy by more than a decade. Glaring health inequalities across the socioeconomic spectrum are often attributed to access to medical care and differences in habits such as smoking, exercise and diet.

But a new study in rhesus monkeys shows that the chronic stress of life at the bottom can alter the immune system even in the absence of other risk factors.

The research confirms previous animal studies suggesting that social status affects the way genes turn on and off within immune cells. The new study, appearing in the journal Science, goes further by showing that the effects are reversible.

The team studied adult female rhesus monkeys housed at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center of Emory University. They found that infection sends immune cells of low-ranking monkeys into overdrive, leading to unwanted inflammation, but improvements in social status or social support can turn things back around.

In the first part of the study, Yerkes scientists put 45 unrelated females that had never met each other one by one into new social groups. Then they watched how the monkeys treated each other to see, for every interaction, who did the bullying and who cowered.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments