How new autocrats curb press freedom

As democratic backsliding has become a global phenomenon and hybrid regimes—a political system which has both democratic and authoritarian traits—have proliferated, freedom of the press has come under threat all around the world. Steps by governments have imperiled press freedoms significantly in the past decade. Freedom House, in its 2019 edition of the annual report on the state of democracy, noted that for the past 13 years, democracy is facing an uninterrupted decline, and that the two institutions seriously impacted by this downward spiral are the electoral process and the media. The growing perils to freedom are not limited to countries which are undergoing democratisation but also consolidated democracies. The long-standing tradition of press freedom in many countries has eroded, pressures on journalists have increased, and more restrictive measures have been imposed over the media and journalists.

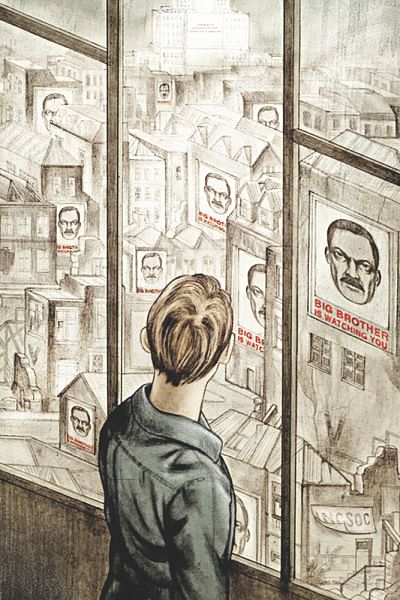

In the old days of blatant authoritarianism, rulers would have employed direct control over sources of information and clamped down on independent media where it was available. News and information which were considered “subversive”, those which were viewed by the dictators as “harmful” were largely pre-censored—we didn’t know what we didn’t know. Censorship was blunt and the autocrats did not want to conceal that they were censoring. This was accompanied with “sanitised information” or “good news”—merely a euphemism for propaganda. Media were largely state-owned and controlled by the government; they were: “His Master’s Voice”.

Under the authoritarian system, the state would have ownership and control over the media which made it easier for them to decide what would be allowed and what would be excluded. But technological innovations and the desire of the new autocrats to adorn themselves with the garb of democrats has made it impossible to tread that path any longer. As the new authoritarians emerged and the global political landscape has changed, techniques and strategies of controlling have changed dramatically. New modes of media control and new tools of muzzling the critics have become normal. What are these new techniques and strategies?

Of course, the new autocrats have not abandoned the tool of censorship. But the mode of censorship is now more sophisticated than ever before. Arbitrarily shutting down media is the last choice of the new autocrats, because it is bad optics and provides an impression that the rulers have acted unlawfully. Instead, the new autocrats are keener on providing the façade of legal actions. Countries which have experienced de-democratisation in the past decade have seen new laws regarding media and information. These laws are harsher than anything ever before, punitive measures are stricter, and they are deliberately vaguely worded, allowing the law enforcers to use these as they wish; these, however, are portrayed as a way of protecting citizens and their interests. These new laws can be broadly divided into three categories: anti-terror, anti-rumour mongering, and protection of privacy of individuals in cyberspace.

The so-called Global War on Terror (GWOT) launched by the U.S. and the West post-9/11 paved the way for these new anti-terror acts in the name of national security. But the scope and nature of these laws have taken various shapes in different countries, expanded over time. Those which joined the GWOT bandwagon used these new laws to silence their critics. The expansion of surveillance, electronic and otherwise, is an intrinsic part of the so called “fight against terrorism” and they imperil the freedom of an individual’s movement and expression at once. Over time, the media and freedom of expression have become the principal targets of these anti-terror laws.

The “anti-rumour mongering” elements of the new restrictive laws are either included in other new laws, or separate laws have been legislated. To a great extent, China showed the way with an anti-gossip defamation law aiming to stop “online rumors” in September 2013. Authoritarian governments, in this regard, use the court as an instrument to justify its actions. In recent years, “spreading rumour” and “spreading fake news” have become synonymous. Since 2016, with the rise of Donald Trump, the concept of fake news has found its way into mainstream discourse. In the past years, laws related to “fake news” have been legislated by many countries.

These new restrictive laws impact freedom of the press in two ways: the threat of punitive measures or punishment, and creating an environment of self-censorship. Governments regularly target individuals and punish them for their unlawful acts. Often by meting out punishment, a clear message is sent to the media institutions and journalists where the line has to be drawn. This is nothing short of coercion.

But the most consequential impact is making self-censorship a common practice. Self-censorship, by definition, is not directly imposed by the government but is undoubtedly, a result of the government’s actions. This is not an unintended consequence but a deliberate strategy of authoritarian regimes. It is what many scholars have described as “strategic silencing”. It is one of the ways of ensuring subservience of the media. These strategies are not limited to the mainstream media but also extend to social media. The enormous control over cyberspace by the authoritarian regimes has been described as “digital authoritarianism”. Often, they are packaged as “protecting individual privacy”, while the government establishes its complete control over private information.

In addition to adopting the strategies of coercion and strategic silencing, new authoritarian rulers have been engaged in an innovative way to limit criticisms of their policies. Lucan Way and Steven Levitsky, in their seminal book titled Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War (2010), noted that in many countries, the media are no longer under the direct control of the rulers. Instead, the rulers allow proliferation of private media; “but major media outlets are linked to the governing party—via proxy ownership, patronage, and other illicit means”. This has become the new pattern in various authoritarian and hybrid regimes. Referring to some of the Latin American countries, Iria Puyosa writes in an article for Global Americans earlier this year, “Funds are directed from the government (through subsidies and advertising guidelines) to sympathetic media. At the same time, independent and critical media face various forms of intimidation, including control over supplies of paper and selective application of tax legislation.”

Loyal supporters and business enterprises are provided with media licenses while opposition and independent media face significant hardships. There are instances of government-backed ownership takeovers to silence critical outlets. These steps not only ensure a domesticated mediascape by limiting contrarian views, but they shape political narratives. These narratives are intended to undermine the legitimate and critical narratives presented, and investigations conducted by independent media.

As for the progressive attenuation of press freedom, another newly devised strategy is franchising censorship, i.e. allowing non-state actors to create an environment which discourages the media from being critical. In these instances, not only does the government remain silent when critical voices are attacked, but leaders and the party often also incite loyalists to attack independent voices and media. “Dissenting opinions are invariably subject to incessant attack and ridicule. Dissidents face a form of character assassination in which their views are twisted to make them appear foolish, radical, unpatriotic or immoral,” mentions Iria Puyosa in the same article. Verbal harassment, defamation, and smearing are often used as weapons against journalists to force them to kowtow. Those who attack the media and journalists enjoy impunity.

Strategies adopted and tools used by new authoritarian and hybrid regimes to curb freedom of press are continuously evolving. Understanding these techniques are imperative for confronting these and fighting for freedom.

Ali Riaz is a distinguished professor of political science at Illinois State University, USA. His recent publication is titled Voting in Hybrid Regime: Explaining the 2018 Bangladeshi Election (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments