Puppetry: The dying art form

It is the year 1971. Standing beside a green paddy field, Yahya Khan and a Razakar are locked in a heated deabate against a Bengali farmer.

Razakar: Koiya dao, Mukti kothay? [Tell me, where is the 'Mukti' (Mukti here refers both to freedom and freedom fighters).]

Yahya: Mukti kidhaar hain? (Where is the Mukti?)

After moving a little ahead, the farmer started thumping his chest and said, "Eikhane, eikhane thake mukti. Buker moddhei Mukti thake" (Here stays the Mukti. Mukti remains in hearts.")

No. These words weren't being exchanged on the battlefield, but on improvised stages run by the legendary Mustafa Monwar in various training camps inspiring the country's freedom fighters during the war.

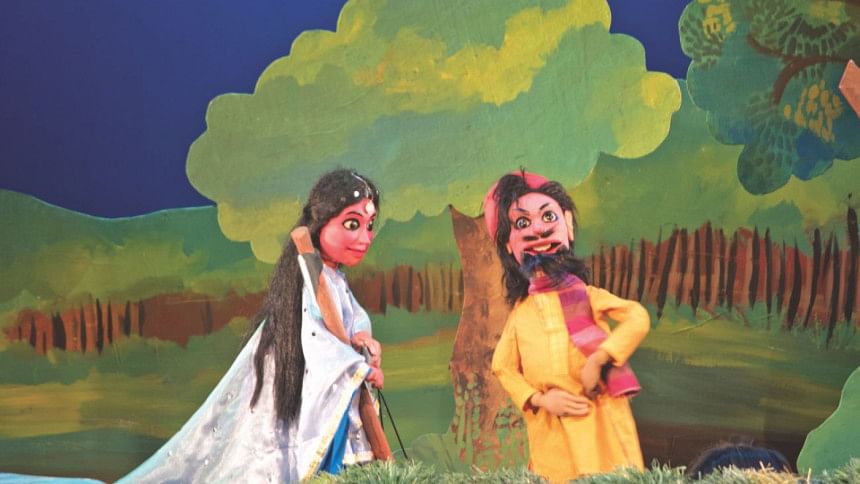

Puppet dance, known as 'Putul Nach', was once the most popular form of entertainment in villages, especially for children, for its visuals, motions, and the power of storytelling. Using string puppets, puppeteers depicted stories of rural people, their lifestyles, religious beliefs, rural cultures and much more.

However, sadly, this industry is gradually fading away. The lack of patronisation, modernism and aggression of foreign culture are some of the reasons behind this trend. Additionally, the interest in the virtual world and the boom in technology is another reason why children have strayed away from this art form. In fact, many of them, especially those in urban areas, are not even aware of the existence of puppet dance.

According to Prof Dr Rashid Harun of Jahangirnagar University's Drama and Dramatics Department, who is also a researcher of Bangladeshi puppetry, puppetry has been on the decline for several decades now.

"In the past, puppeteers would enchant the villagers with stories that had mythological, historical and social themes, for example, Ramayana, Gazir Gaan, Kushan songs etc., and they enjoyed a widespread popularity then. However, after partition, puppet artists, most of whom were Hindus, left the country and the puppet industry drastically changed," he says.

Those who did not leave or kept the puppets from the then artist, continued the profession, but there was a fall in the quality. "The religion factor during the days of East Pakistan made it worse with people suddenly having problems with dolls and statues," he adds.

During the War of Liberation, more Hindu puppeteers left for India, further widening the existing void. Although religious sanctions were no longer an issue after liberation, puppetry still struggled to rise from the ashes. Since puppet making, scripting and stories had not been developed for a long time, village puppeteers gradually started losing their stages due to the lack of interest among the audience.

62-year-old Balaram Rajbongshi, a puppeteer from Jhitka, Manikganj, who started his Putul Nach journey at the age of 11, recalls the golden days when puppetry still occupied the public imagation. "In the 60s, we did shows travelling from house to house to enchant people with our stories—Ravaan Bodh, Sheetar Biye, Kamala Ranir Banabash etc., Later on, we expanded our activities to different fairs. I can still remember, we would do shows six months at a stretch, from the Bengali month Kartik to the day of Chaitra Sangkranti".

However, the introduction of obscene dance shows by young women under the same name, a large section of the audience, especially women and children, started to boycott the puppetry shows. "The same audience that had clapped and chanted for us once, now looked at us with scorn. In fact, it became increasingly difficult to get permission from the local governments and thanas for the Putul Nach in different fairs and other occasions," says Rajbongshi.

"At present, we get 5-6 shows a year, mostly in Annaprashanas (an infant's first intake of food other than milk), Chaitra Sangkrantis, Baishakhi Fairs and sometimes in television channels," Rajbongshi adds.

Rajbongshi gets BDT 25,000, on average, from a show and he needs to distribute it amongst seven members of his team. Since the remuneration is neither regular nor satisfactory, he has had to switch his profession to fishing, and do puppetry on the side.

Mustafa Monwar, argues that there have been attempts by locally influential people to persuade puppeteers to create educated stories about issues like family planning: "But in the end, they fail to entertain people. The beauty of puppetry lies in its whimsy, in its ability to make people laugh. If you try to push it down people's throat, its charm is lost."

With puppet shows on the decline in rural areas, Monwar has worked very hard to modernise the shows. His love for puppetry made him introduce puppet shows on Bangladesh Television in 1966. Shows like Ajob Deshe, Sob Desher Golpo, Moner Kotha and many others were successful as well. His puppet characters Bagha, Meni, Parul, Gittu and Baul, even today evoke nostalgia among many of us.

The style of Mostofa Monwar was also very unique, as he used to operate rod puppets which were manipulated from below with rods. He also introduced some modern techniques where the puppets would move their eyes, mouths and many other parts of their body, making them seem even more animated.

There are still a number of puppeteers and young artistes, who yearn to go ahead with puppetry. But in reality, how much support are they getting?

"Currently, there are only 50-60 puppet teams in the country. Of them only 10-12 groups are doing shows in different fairs. Though the new generation of artistes is very earnest, the limited amount of opportunity they get is a concern," says Dr Harun.

Arthur Baptist, creative director and senior researcher of the Dhaka Puppet Theatre shares similar concerns. "Being a puppet artist is very challenging today. For example, to maintain a puppet team, we need an office, a space for regular rehearsal and a workshop, which require a handsome amount of money. But if we give BDT 2,000 to a puppeteer after a stage show that takes more than 10 days to rehearse, how can s/he take puppetry as his or her only profession?" says Baptist.

He also argues that the budget for puppet shows in corporate events is very little, adding that there is a need for corporate sponsorships and proper support from the government so that they can arrange shows in different schools and areas of the country.

Mustafa Monwar believes we have a tendency to not promote practices derived from our own cultures, preferring rather to embrace foreign cultures. "In terms of saving puppetry, our reluctant attitude and lack of proper patronisation has always been evident. Though Shilpakala Academy is willing to help, no significant initiative has been taken," he says.

Puppetry had and always will have an indomitable power to spread important messages to its audiences in the form of pure art and entertainment. If we can create a platform, where our young puppeteers can come, practice and do research to develop our industry with new stories and characters, it will not be very difficult to revive this art form. In addition, if government and non-government organisations frequently arrange puppet shows, it would infinitely be helpful for our puppeteers.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments