The uphill task to receive an education in the camps

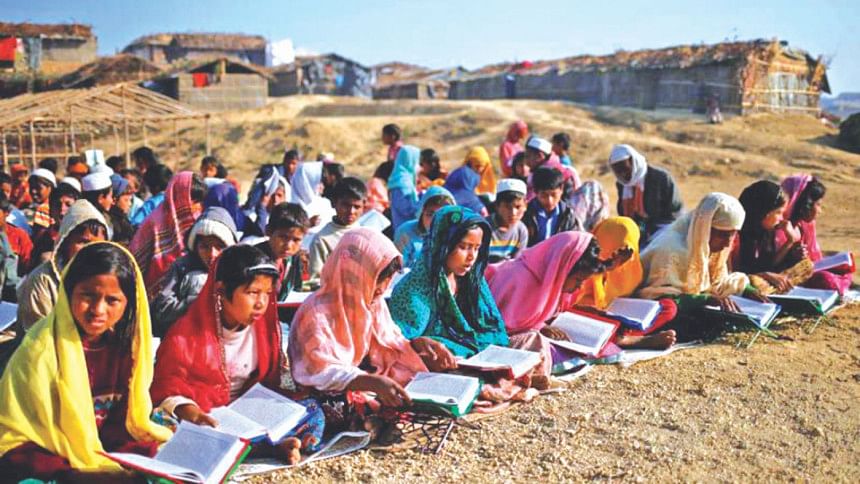

On a recent visit to the camps, a young Rohingya boy, who proudly wore a bright blue UNICEF backpack, took us to his school. It was only a little larger than the bamboo huts in which the refugees live. Called 'learning centres' (note that these cannot even be called 'schools'), these are the best hope of an education for children growing up in the camps.

Rohingya children learn English and Burmese (learning Bangla is also strictly forbidden by the government) and math. As of March, 1,991 such centres are operating in the camps, where 180,293 children are enrolled. However, over 39 percent of children aged three to 14 don't attend the learning centres and 97 percent of those between 15 and 24 have no access to any education facility, according to the 2019 joint response plan compiled by humanitarian agencies.

Rohingya refugees have no access to formal education in the camps. Learning centres, run by the UN and NGOs, are dismissed by many parents as places for their children to learn rhymes and songs and play, and not where they can receive a quality education.

Bored, many children drop out. The local government and UN agencies were reportedly at loggerheads last December, with the former accusing that the latter were essentially inflating enrollment numbers for donor funding, by failing to track dropouts.

Refugees who have money pay for private tuition in the camps—largely religious education or learning a Burmese curriculum from educated refugees. Madrasas, in particular, flourish in the camps. After exhausting all options in the camps, some parents have gone the extra mile to obtain papers, most notably birth certificates, to get their children enrolled in local schools. Studying in local schools means that Rohingya students can then sit for national examinations and potentially go on to college.

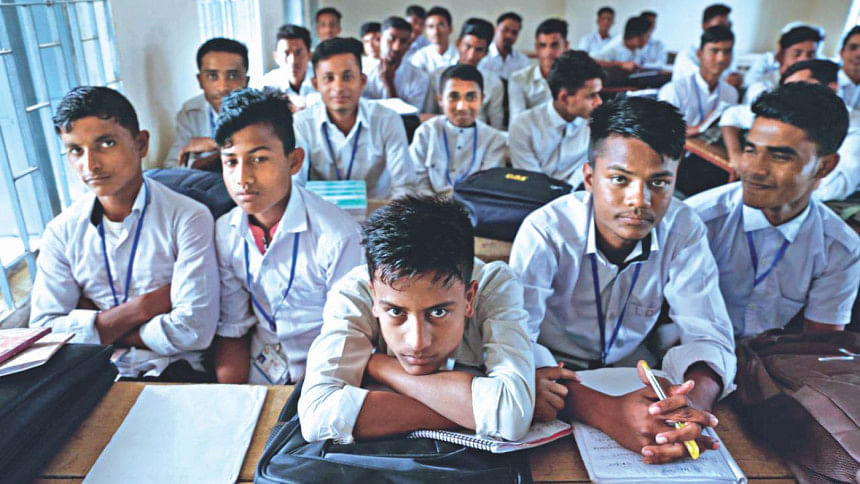

Following a government notice instructing secondary schools in Teknaf and Ukhia to expel Rohingya children, many of these students have been expelled since January. Human Rights Watch viewed the government notice—which detailed the students' names, their camp addresses, and schools—and interviewed 13 expelled refugee students. Most of them were in grades nine and 10, nearly at the end of their high school education, when they were expelled.

Rohingya students were publicly called out in classrooms, their hard-won ID cards and books taken from them, and told to leave. 64 students were expelled from Leda High School alone, the area in Teknaf being host to Rohingya refugees since the early 1990s—in the formally registered camps nearby and informal camps which grew up around them.

The expelled students come from the families of registered refugees in the Nayapara and Kutupalong camps, run by UNHCR and local authorities. They were declared refugees by the Bangladesh government back then and are protected under international law (as opposed to the more than 900,000 refugees who have arrived in Bangladesh since, the largest numbers having arrived in August 2017). These children were able to study up to class eight in the registered camps.

Under international law, particularly the Convention on the Rights of the Child (which Bangladesh is signatory to), children have the right to education—free primary education as well as access to secondary education and higher education.

At first, non-formal schools in the registered camps allowed children to receive some education following the Burmese curriculum. Since 2007, an adapted version of the Bangladeshi school curriculum was allowed in these camps by the government upto grades five (subsequently, extended to grade seven). After class eight, these students have no other option.

In informal camps, which host the majority of the refugees, students only have access to education up to class five. All education provided in the camps is unaccredited, meaning students don't receive any certificates and are unable to sit for national examinations—which would allow them to continue on to or finish high school.

This has meant an uneven education for Rohingya children with changing curriculums leading to many having to repeat years of school or dropping out in the process. Overcoming these barriers, by repeating grades in their camp schools and excelling in official PSC and JSC exams, some students managed to enroll in local high schools with the encouragement of their camp teachers and schools impressed with their good grades.

One student interviewed by Human Rights Watch said his family borrowed money and used savings to be able to pay Tk 3,500 for a Bangladeshi birth certificate. Another, 15-year-old Mohammed Yunus said he worked in the brickfields to pay to attend the local school—now that he has been expelled, he works full time as a day labourer.

"The Bangladeshi government's policy of tracking down and expelling Rohingya refugee students instead of ensuring their right to education is misguided, tragic, and unlawful," said Bill Van Esveld, a senior researcher of children's rights, in a statement released by Human Rights Watch in April. "Education is a basic human right. The solution to children feeling compelled to falsify their identities to go to secondary school isn't to expel them, but to let them get the education they deserve."

***

Rohingya children, comprising 55 percent of the camps' population, and adolescents have been termed by the UN as a "lost generation" for having no access to formal education or vocational training.

"Young people who attended school back in Myanmar now just roam around the camps without any hope and children are growing up in a society where there is a lack of every right except food," says Razia Sultana, a Rohingya activist who has lived in Bangladesh since childhood.

"Now, most essential for my community is basic education up to the eighth grade in the camps. The facilities and circumstances currently allow only up to the third grade and that too, is not actual education but are more like day care centres," she continues.

"Education is key to moving forward and for the self-identity of the refugees."

Those who were able to escape the dreary confines of education in the camps, have seen rewards. While many parents struggle to ensure secondary schooling for their children in or outside the camps, some of those who managed to finish high school in Myanmar or here in Bangladesh have managed to even attend higher education.

19-year-old Formin Akter, is one of 25 Rohingya students enrolled in the Asian University for Women in Chittagong. She was profiled in a Reuters story, where parallels between her and her sister's lives were drawn—Formin and her older sister Nur Jahan both managed to complete their high school diploma back in Myanmar, the first from their village to finish high school. They, along with other family members, fled to Bangladesh in late 2017.

While Formin is now off at university on a full scholarship, Nur Jahan being the eldest of the siblings was married off to a fellow refugee last year. She now teaches younger children in a learning centre in Kutupalong camp, as did Formin before arriving at university.

Formin agrees that the learning centres are not adequate for a good education. "There are only learning opportunities for small children—they are learning their ABCs, songs, and basic writing," she says. "It is not good enough for older students."

While Formin is a recently arrived refugee and spent only a year in the camps, her 21-year-old classmate Rupia Mahabuba comes from a family who have lived in Ramu upazila in Cox's Bazar for generations. She studied at the local school and is now attending university. In comparison, Rohingya women and girls their age and younger are generally seen in the camps doing chores, running households, and raising children in the camps.

While Formin was able to attend university only because she managed to finish high school through sheer persistence back in trouble-ravaged Rakhine and Rupia lived outside the camps, those inside face an uphill task to even complete their primary or secondary schooling let alone think of university.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments