Framing the injustices against RMG workers in Bangladesh

On April 24, 2013, the collapse of Rana Plaza—a building that housed seven garment factories in Savar—killed at least 1,176 people. This collapse is regarded as the deadliest disaster in the history of the garment industry. It was, however, neither the first nor the last industrial disaster in the countries' apparel sector. The collapse attracted worldwide attention to working conditions in Bangladesh. Due to inadequate support from the state, activists and mass people had to be watchful about fulfilling emergency rescue tasks. Alongside street protests with various demands, activists undertook artistic and creative ventures to protest the lack of labour rights and safe working conditions in the sector. Most of these artworks emphasised on arousing primary reflexive (anger, grief, outrage, shame) and complicated affective emotions (compassion, trust, hatred) in the public discourse.

Framing injustice against the garment workers

Through two songs, one exhibition of a memorial quilt, and one street play—all from a book of anthology published in 2016 by Bangladesh Garment Workers Solidarity—I show how "activist" artists in their works utilise the deliberate process of framing against injustices using affective emotions. Scholars categorise emotions either as reflex emotions (fear, joy, shame, outrage), which come and go quickly, aroused by stimuli, or as longer-term affective commitments (love, hatred, compassion, trust, empathy), which take time to grow, remains longer and whose arousal is much more complicated than that of reflex emotions. Affects are positive and negative commitments that protestors have toward people, places, ideas, and things. Commitment to a group or cause may be based on instrumental calculations and morality, but it is also based on affection: to help those they love and punish those they hate. Trust and compassion are complex cultural feelings, especially important to altruistic movements with little overlap between activists and beneficiaries. The aforementioned concepts will be used in the following section to show how activists, after the Rana Plaza collapse, framed their protests trying to incite different kinds of emotions among their audience.

The first song is by activist band Samageet, who wrote it after the collapse to create awareness about inhumane working conditions in general and to protest the deaths at Rana Plaza. The lyrics are by Amal Akash, who also composed the music alongside Khalequr Rahman Arko. I cite from Shahidul Alam and Rahnuma Ahmed's translation:

"Can you hear me out there?

Hey people, can you hear?

Corpses piled high, brick rock concrete

Bury not a throbbing heart, I still breathe.

Bury me not alive

Mother, o mother

I still breathe life."

Here, the emotion that the artists want to arouse among the audience is the reflex emotion of anger, but soon we realise that the broader goal is to incite outrage towards an irrational and inhumane system that traps the workers in a factory building and kills them. The wounded in the Rana Plaza debris were stuck; some had to be rescued by cutting their limbs off. Despite the situation, they wanted to live—through these lines, the workers seem to remind us that in the debris of the readymade garment sector before the big collapse, they were still stuck under the juggernaut of high output and production that is piling corpses high and crushing the workers under its concrete greed. They want compassion from the citizens of Bangladesh to let them live, and for the global retailers to let them have decent wages. These activist singers are reminding us of that moral obligation by using words like brick, rock, concrete - those that constituted the scenes from the collapse.

Another song titled No More Press Note, written and composed by Kafil Ahmed and translated by Naeem Mohaiemen, exposes how governments, one after another, approve unacceptable working conditions in the sweatshops of Bangladesh. The song reveals working conditions where factories are like prisons and when the workers die there, the government only issues press notes without taking any responsibility. As a result, nothing changes over the years. The singer wants the governments to do something concrete to bring change to the inhumane working environment:

"You have locked me up

You have burnt me to death

Press Note, only Press Note

I don't want, I don't want any more Press Note

Trapped in this suffocating room

I defy my prison

I defy your prison

Why is factory a jail for thousands

Why is life frozen like this

Endless work but we never get paid

We don't earn to even live"

Here the words of defiance are used by the artist to arouse a sense of urgency to protest the extant situation. They portray the dream of the workers to have a better life, away from greed and exploitation. These songs were written and performed by activists who organised cultural events to protest the deaths in Rana Plaza, and raised money to do rescue work, treatment, and rehabilitations of the victims. This is how activists frame injustice using words that demonise the greed of global economy in its global periphery.

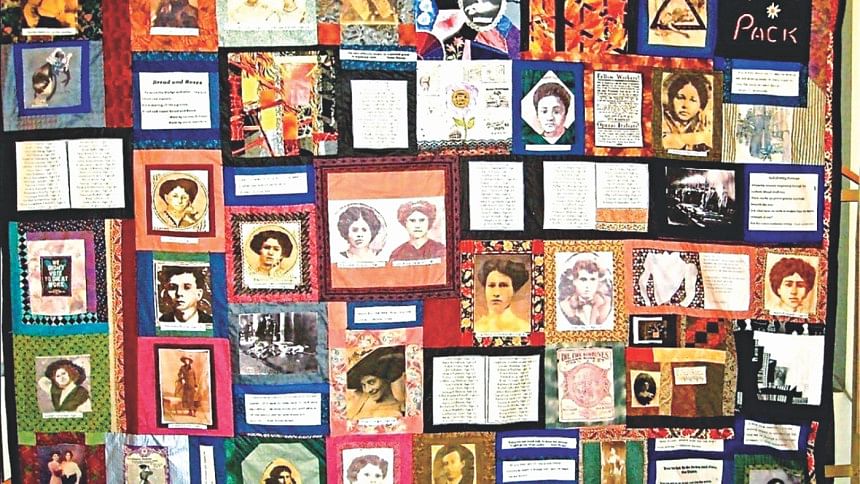

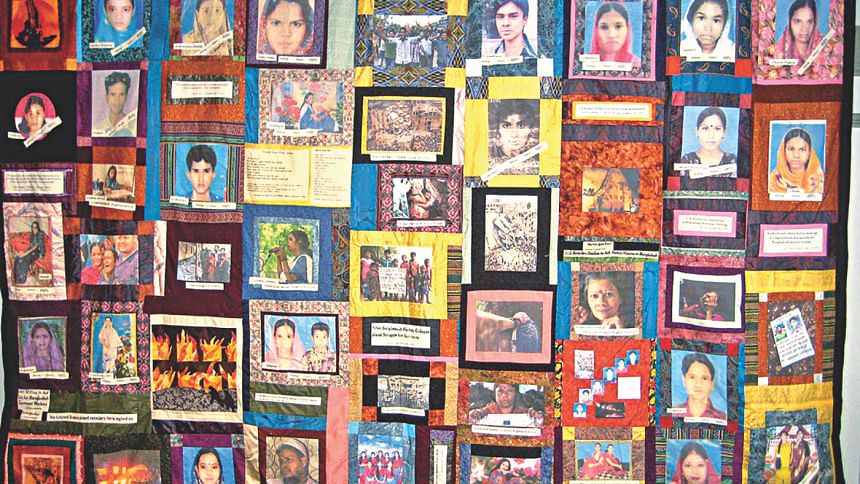

Another effort to make us remember the disaster that also resonated with global consumers and activists is portrayed and sustained through photography exhibitions using Bangladeshi photographs and juxtaposing it against that of New York's Triangle Factory Fire more than a hundred years ago. Robin Berson created a 'memorial quilt' similar to the one she created for the Triangle fire victims, with photographs of the Tazreen and Rana Plaza victims. Photos were collected from the posters hung by relatives searching for missing workers in Rana Plaza. Thus, she juxtaposed the faces of American women with that of the women who lost lives in Bangladesh a century later, in similarly brutal working conditions. It serves to remind us that although the line of production they work on is endless, workers of the developing world, including Bangladesh, work under brutal, inhumane, and unsafe conditions. Berson hopes that the quilts will elicit empathy among the viewers for the humanity, beauty, and fragility shared by the dead youths. At the same time, they can strengthen the sense of moral kinship and responsibility among people all over the world.

As an activist performer, playwright, and researcher, I have also resorted to framing injustices in my creative work on workers in Tazreen and Rana Plaza. Through my play Jatugriho (The House of the Melted Wax), produced by BotTala (a performance space), I wanted to remind audiences what these victims went through. We should not forget the names that were crushed under greed, lack of empathy, and lax governance for the sake of development, output, and production. I did not want anyone to forget how a person alive must have felt to burn to death. What they were thinking during their last moments! Corpses were found in Tazreen in embraces just as they were caught on camera in Rana Plaza. But their families did not receive compensation, missing victims were not identified even after DNA tests, local owners of the factories in Rana Plaza and BGMEA did not pay a penny in compensation. In such a setting, in my play, dead bodies in body bags on a van rickshaw begin to talk. They say that no one killed them, they just died. A song opens the play:

"Jatugriha burns, the bees burn too

The Pandavas had a tunnel to escape

But we have no exit.

Still, no one killed us

We just died."

The reflexive emotion—outrage—was incited through the play, often performed on street corners and open places in RMG areas, and the audience were mostly workers. The play ends with a song by Kafil Ahmed that, against all the odds, continues to sketch the dream of better working conditions. The play was translated by Munasir Kamal and Saumya Sarker and directed by Mohammad Ali Haider.

In the play, Nobi, a van rickshaw puller, while paddling the rickshaw full of body bags from the Tazreen fire, says: "Are you a man or the devil? How much more do you want, you thief of thieves? So many people! So many dead bodies! Burnt to ashes! Ashes and charred remains! They have murdered so many people!"

Then the dead workers tell their story, their lives, aspirations, and the violent and excruciating ending. They tell us about how ridiculously owners claim that whenever the workers want their dues or better working conditions, they are "conspiring" against the industry. It creates a reality where they live on very low wages, inhumane personal vulnerabilities, and brutal working conditions, in order to create profit for a very small group of people who are irresponsible and greedy and want to earn more money disregarding the worth and dignity of the workers' lives.

The Rana Plaza collapse and its aftermath saw changes in the working conditions of garment factories in Bangladesh. Though I would be wary of over-generalising such success, much of it can be attributed to the long-continued efforts of activists and general citizens working to end such heinous labour practices. Activist artists framed those injustices through the emotional messages of compassion, which helped create moral obligation for people to work against such brutality.

Samina Luthfa is associate professor of sociology, University of Dhaka and creative director of BotTola.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments