The Fluid Personality Conundrum

Liquid (noun) [C/U]: a substance that flows easily and is neither a gas nor a solid.

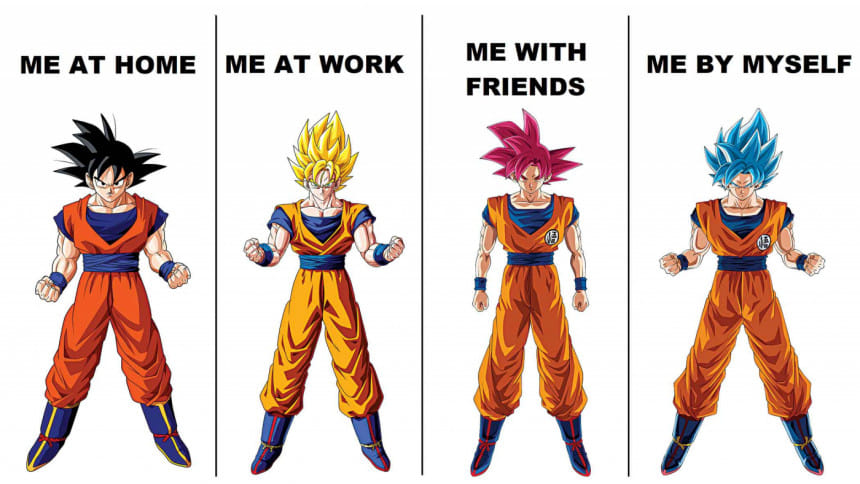

From the given definition, we can gather that a liquid's most distinguishable characteristic is its ability to conform to the nature of its surroundings, be it a vessel or just a flat surface. Could the same theory be applied to people who mould different aspects of their personalities according to the company they keep?

Upon conducting some research on the theory, we came across the following from a behavioural study:

"A surrounding environment often influences which information needs to be attentively processed in certain ways and also determines an appropriate action set or behavioral repertoire. That is, the surrounding environment often determines the modus operandi of the brain." (Choong-Hee Lee & Inah Lee, 2013)

So, essentially, people adapt to the people around them, with the latter's behaviour acting as different stimuli influencing the former's behaviour. In the pursuit of being accepted by just about everyone, it's hard to stay constant – to be just one version of yourself.

It's this pressure that influences people's decision to conform. Trying to be well liked becomes an addictive practice in people's daily lives, almost instinctual at one point. When you're amongst family, chances are, you'd want to make your parents feel proud of you, the entirety of your existence. The only way to ensure that happens is to take on the role of the family favourite. In order to add further meaning to that sentiment, you might just throw in some steadfast obedience and you'll fit right into a conservative Bangladeshi family. This isn't always a forced adaptation of course; for family-oriented individuals, family is the biggest source of comfort.

Being around friends, on account of potentially sharing similar goals and ideas, calls for a more laid-back attitude in the case of others.

Samantha Khan*, 20, says, "I have an incredibly difficult time having a proper conversation with my parents. With my friends, there's this sense of liberation where I know I won't be judged for any of my choices. They offer me a sense of comfort that my parents can't."

Offering a different perspective of parent-child interactions, 24-year-old Ishmam Khandaker* says, "My equation with my friends is a bit more relaxed as I don't feel responsible for them the way I do with my parents. With my family, I'm more practical. With my friends, I'm another dorky kid."

However, people occasionally tend to over-indulge in carefree behaviour around friends and become highly susceptible to some degree of recklessness.

In an office environment, the situation varies even more as you find yourself attempting to strike a balance between professionalism and friendliness. Overstepping boundaries is unacceptable. Therefore, you bring out your somewhat reserved self, one who doesn't laugh too loudly and refrains from communicating in terms deemed inappropriate for workplaces. Finally, when you're by yourself for a brief moment throughout a day, you feel… conflicted, about yourself. The conundrum presents itself.

Prioritising different aspects of your personality in different social circles, are you losing sight of who you really are?

Perhaps this is where the harm lies in your efforts towards fitting in. The fear of being the odd person out, the discomfort associated with a lack of popularity, the peer pressure to conform, has perhaps led you to a state of dissociation within yourself. The end result is a personality, fractured. The more you try to become everyone else, the less you become of you. The conundrum intensifies.

Let's take a look at how the Covid-19 pandemic has factored into our social interactions.

Portraying different aspects of your personality according to context can indeed get more complicated during a period of isolation, where there's a lack of stimuli in the surrounding environment. They could be flabbergasted upon seeing someone after a very long time, finding themselves at a loss for words despite having many thoughts run through their heads. To the friend they are speaking to, they may just seem spaced out. This may cause them to hug the concerned individual to help make up for the words lost, despite being the human equivalent of a tree: extremely uncomfortable to hug (during pre-pandemic times).

Of course, extroverts are perfectly capable of remaining... extroverted. The pandemic may even make you want to be more outgoing than before. You could find yourself speed walking in parks making conversation with strangers. You may be unaffected by the pandemic, as was with Dolly Zaman*, 22, who said, "My communication from the hostel with both my family and friends were over phone/social networking sites. So not meeting many people didn't affect me so much. But I did miss the casual face to face meetings with my friends and batch mates."

If you were already an introvert, the pandemic may have contributed to your general appreciation of being at home, says high-schooler June Rahman*, "I am believed to be extroverted around school friends, but in general remain aloof and cold to others. During the pandemic, I have found myself to be communicating more with everyday faces than I used to in the past."

Meeting someone outside of those from home could cause you to stammer or forget words while attempting to converse. Two approaches to dealing with this issue could be to either fake an emergency and run for your life to hide from embarrassment or to honestly explain how you are not used to conversations with anyone outside of home in recent times and will take some time to get used to things.

There's always the risk of misconceptions arising due to the changes in behavioural aspects selectively occurring depending on the social group you are with. Being less able to speak with people you do not see often, but perfectly conversing with others at home, being known for being as stiff as a tree when it comes to hugging but willingly giving bear hugs to loved ones, telling your family you abhor walks but being known for loving walks with friends are all tiny inconsistencies in your behaviour in social groups that once identified, could cause those who know you to doubt the authenticity of your personality.

This is because even the trivial habits and personality attributes you see in an individual give you a sense of familiarity. Such trivial characteristics are combined to constitute your general idea of the person and helps you identify them. If these characteristics do not hold true, you ask yourself, do I really know this person? Did they pretend to be a certain way in order to get along with me? If so, do they have an ulterior motive? Before you know it, the concerned individual may be deemed as untrustworthy.

Step one to overcoming this issue is to accept yourself as you are. There is no superior personality, there is only what is deemed as morally incorrect and correct. Seeking self-improvement should not be correlated with the alteration of opinions or aspects of your personality that are not causing harm. Therefore, there is no need to, for example, convince yourself of being fond of a popular music genre or a particular hobby when amongst a particular social group in order to engage in conversation with them.

Keeping up appearances is hard as is, and being true to yourself cannot only help increase self-confidence, but also other's confidence in you by making you seem to be genuine. According to psychiatrist and author Joanna Cannon, "Instead of living our lives in monochrome, it might be more fulfilling to search for the colour, and the variance, in those around us, and we can then allow ourselves to be accepted for who we really are – not for the fragments of our characters we allow people to see."

Human personalities can be very complicated, and complexities aren't necessarily flaws. Deviations in behaviour according to context are a survival skill that may just exist eternally. The conundrum will always be there.

*Names have been changed to protect privacy

References

1. National Center for Biotechnology Information (May 10, 2013). Contextual behaviour and neural circuits.

2. Psychology Today (July 13, 2016). We All Want To Fit In.

Bushra Zaman likes books, art, and only being contacted by email. Find her at [email protected]

Rasha Jameel is your neighborhood feminist-apu-who-writes-big-essays. Remind her to also finish writing her bioinformatics research paper at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments