AT A LOSS FOR WORDS

"I have no knowledge of the script of my mother tongue, Kokborok. I face some problems while having lengthy conversations as well. It definitely bothers me," expresses Prerona Roaza, a member of the Tripura community — one among countless others who did not have the privilege of being educated in their mother tongue.

THE CURRENT STATE OF INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES

The only nation in the world to have fought for the right to speak in one's own language, Bangladesh is better poised than any other nation to comprehend the significance of a mother tongue. According to a survey by the International Mother Language Institute conducted in 2015, there are currently 41 languages spoken in the country, of which 35 are identified as indigenous [1]. Of these, the languages spoken by the Chakma and Marma people have their own script, the Tripura use the Roman script, and most of the rest use the Bengali-Assamese alphabet.

However, while these scripts exist, they are not widely learnt, or practiced, even by their native speakers. From primary levels indigenous children are subjected to an abrupt shift in their mode of learning, having to use mainstream Bangla to learn all other subjects e.g. science and mathematics. As a result, their proficiency in their own mother tongue is put at risk.

"It bothers me that I didn't receive the same institutional training in Kokborok that I did in Bangla," states Roaza. "Languages die out with the death of their fluent speakers. So, it is very important to have academic preservation and training."

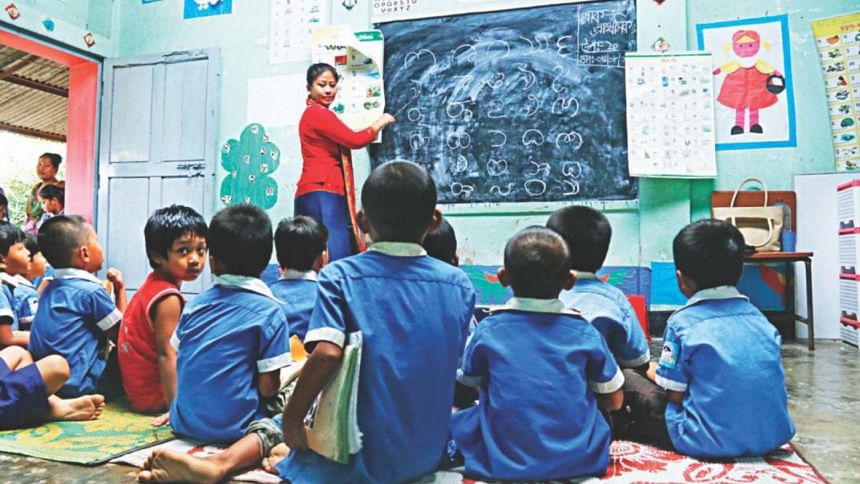

Ipsita Chakma Juthi, assistant teacher at Nunchari Prakalpa Gram Government Primary School, reveals that despite only two of the students in her class being non-indigenous Bengali, the medium through which they learn all other subjects remains Bangla. This creates a deep chasm of learning within these kids, and an uphill battle for the teachers. The students struggle with the rift between the language spoken at home, and the language taught in class from the very beginning. All concepts are first taught pictorially and in Bangla, which they don't understand. Then, at the teacher's own initiative, the concepts are explained to them in their own indigenous language, Chakma, so they can make that connection between concept and understanding.

"They struggle with this language barrier till middle school. They are drastically falling behind. Once when I first joined back in 2017, I was teaching a class of fifth graders, which is quite a senior class, and I had asked a student to read out a passage in Bangla and they couldn't do it. It was heart-breaking," expresses Juthi.

This struggle by the students has led to certain families trying to give their children an "advantage" by speaking Bangla with their children from birth. However, as Juthi conveys, this results in dissociation from their personal indigenous heritage, and could be termed as "aiding the extinction of a language."

WHY ARE THESE LANGUAGES ENDANGERED?

The reasons behind the endangered state of these languages are discussed by Professor Sourav Sikder of the Department of Linguistics, University of Dhaka. He mentions, "It is the norm all around the world that when a majority language exists — such as in Bangladesh where 98 percent of the population speak Bangla — minorities and their languages encounter some discrimination."

He also identifies the lack of economic incentive as a reason behind indigenous people not learning their written scripts. A purist, who only speaks their indigenous language and neither Bangla nor English would be at an enormous disadvantage when seeking a job in the already competitive job market of Bangladesh.

Primary school teacher Juthi expresses, "We have to earn, we have to compete with the rest of the country, and also we need to have educational degrees. The degrees which are very significant in our country are all taught in Bangla. So, we were acclimatised to Bangla, and then English beside that."

NATIONAL SOLUTIONS AND PROPOSALS

In 2010 the National Education Policy was enacted by the government of Bangladesh, sections 18, 19, and 20 of which concern the education of indigenous populations [2]. It finally allowed indigenous children to go through primary school in their own mother tongue. In light of this policy, in 2013 the government announced that they would release primary level books in the five most widely spoken indigenous languages. Since then the government has been working on releasing these books.

"Those involved in the development of the curricula have been working on it for quite some time," reveals indigenous leader Badhon Areng, General Secretary, Cultural and Development Society (CDS), who was personally involved in the development of the school books for the Garo community [3]. "I have been holding workshops with representatives of the Garo community since 2010. We decided to consult the community and take on their advice in order to device the optimal curricula for these books."

"Many Garo people can't speak or write accurately in their own language today because they didn't get chance to study their language at school. The books are like a gift for our people. We have been working on this and waiting for it for a long time," expresses Areng.

In 2017 the first editions of the primary books were published [4]. Juthi reveals that these books are now available till the fourth grade, but introduces us to the main problem regarding their utilisation.

"I don't know how to read the Chakma script. Most people of our generation don't. We did not have these books when we were kids. As children we were always encouraged to learn Bangla, and so we didn't have the initiative to properly learn our own scripts. Now, even though these books exist, there are not many teachers who are qualified to teach them," the 30-year-old teacher recounts.

Lack of teachers' training is also mentioned by Prof. Sikder, who expresses that this is one reason why the primary school books in indigenous languages are not being utilised to their full extent.

"I have put forth a proposal where primary school teachers, whose mother tongue is not Bangla and who know how to read and write their scripts, will be prioritised for hire in indigenous-majority schools. Such a step introduces economic incentive to learn the written scripts of Chakma, Marma, and other indigenous languages," states Prof. Sikder. Organisations such as SIL Bangladesh have taken the initiative to conduct teacher's training in order to improve the situation [5].

WHAT WE CAN ADOPT FROM INTERNATIONAL SOLUTIONS

The problem of indigenous languages being endangered is not unique to our nation. This issue is encountered wherever indigenous populations are minority groups. By inspecting the methods employed by other nations to confront this situation, we may find the key to preserving our own indigenous languages.

Four successful programmes to revive and preserve indigenous languages are detailed in a 1997 report by Dawn B. Stiles [6]. In his report, Stiles examines the following indigenous language programmes: Cree Way in Quebec, Canada, Hualapai in Arizona, Te Kohanga Reo (Maori) in New Zealand, and Punana Leo (Hawaiian) in Hawaii. For each of these programmes, before they were set up, the languages were endangered and were not being passed on to younger generations. The programmes developed unique curriculums that were tailored to the needs of the indigenous population, and they combined community support, parental involvement, and government funding.

The concept of not separating the culture from the language was paramount. The programmes incorporated the historical background of these indigenous people into the curricula themselves. They also dealt with the problems which schools in Bangladesh face, such as lack of trained teachers and written materials, by involving the parents and elders of the communities in the programmes. It was discovered to be of utmost importance to the success of the programmes that they were started at an early age, and that written teaching materials were made available.

Data from a Native Language Shift/Retention Project in the United States, suggests that immersion schooling can "serve the dual roles of promoting students' school success and revitalising endangered indigenous languages." [7] Teaching primary levels in indigenous languages has been seen to be successful. The development of immersion schools that teach in indigenous languages is a proven method of ensuring their survival, since it enables new speakers to preserve and enrich the language.

In these times of globalisation the world is at constant risk of homogenisation. Diversity in language, which extends to diversity in culture, is threatened by the constant race for productivity, efficiency, and other capitalist sentiments. However, in all its haste, this race doesn't take into account the harm done to concepts of identity, self-esteem, and motivation of individuals. Preserving indigenous languages is one of the first steps in preserving indigenous culture, and the broader concept of diversity in general, without which the world just gets closer to being one undesirable homogenous unit where humans and machines are nearly indistinguishable.

References

1. Hasan, Kamrul. "Could 2019 Truly Be the Year of Indigenous Languages?" Dhaka Tribune, 20 Feb. 2019, www.dhakatribune.com/opinion/special/2019/02/21/could-2019-truly-be-the-year-of-indigenous-languages.

2. Shuhel, Mikrak Mrong. "Indigenous Language in Education." The Daily Star, 15 Feb. 2016, www.thedailystar.net/law-our-rights/indigenous-language-education-511519.

3. Nongmin, Sumon. "Workshop Aims to Save Tribal Language." Ucanews.com, 4 Nov. 2014, www.ucanews.com/news/workshop-aims-to-save-tribal-language/34627.

4. "Learning in Your Mother Tongue." Dhaka Tribune, 24 Feb. 2019, https://www.dhakatribune.com/special-supplement/2019/02/24/learning-in-your-mother tongue.

5. "MTB-MLE--Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education." Multilingual Education | SIL Bangladesh, SIL Bangladesh, 2019, www.silbangladesh.org/language_education/mle.

6. Stiles, Dawn B. Four Successful Indigenous Language Programs. Educational Resources Information Centre, 1997, ERIC No. ED415079.

7. Mccarty, Teresa L. "Revitalising Indigenous Languages in Homogenising Times." Comparative Education, vol. 39, no. 2, 2003, pp. 147–163., doi: 10.1080/03050060302556.

Rabita Saleh is a perfectionist/workaholic. Email feedback to this generally boring person at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments