India’s democracy in detention

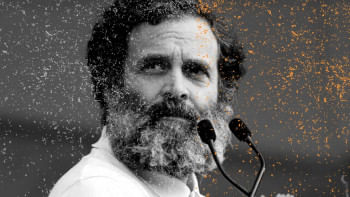

The sentencing of Rahul Gandhi, the leader of the opposition Indian National Congress, to two years in prison, and his disqualification as a lawmaker in the Lok Sabha (the lower house), has sent shockwaves through India's political system. Beyond reverberating through both houses of parliament, the episode has opened a new and sorry chapter in India's political history, and cast serious doubt on the future of its democracy.

Gandhi was targeted over comments he made during a 2019 campaign speech in the southern Indian state of Karnataka. After discussing India's economic travails, Gandhi named six "thieves" who had contributed to them: Nirav Modi, Mehul Choksi, Vijay Mallya, Lalit Modi, Anil Ambani, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi. "One small question," Gandhi quipped, "how are the names of all these thieves 'Modi, Modi, Modi'? Nirav Modi, Lalit Modi, Narendra Modi, and if you search a little more, many more Modis will emerge."

It is obvious that Gandhi was calling out specific individuals for allegedly looting India's economy, before delivering an offhand observation that three of them happen to share a surname. You might say that there was no need for Gandhi to comment on their name at all. But politicians, including many from the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), have said far worse in election speeches about all sorts of groups – from rival politicians to minorities – with no criminal case brought against them.

To claim, as BJP lawmaker Purnesh Modi did, that Gandhi's quip defamed the entire "Modi community" as thieves is, at best, a stretch. And to rule, as a court in Surat in the western state of Gujarat did, that it constitutes criminal defamation meriting the maximum possible punishment is worse than suspicious.

The story gets murkier. The judge who first heard the complaint in 2019 mused aloud that it did not seem to have much substance. Rather than risk having his case dismissed, Purnesh Modi rushed off to the High Court to secure a stay of his own petition. Then, two years later, Gandhi made a speech in parliament (largely expunged from the records) accusing the prime minister of crony capitalism, and Modi scurried back to the High Court to get his stay lifted.

A more united opposition would be bad news for the BJP, which holds 60 percent of seats in parliament, but won just 37 percent of the vote in the 2019 elections. If a majority of the 35 other parties in parliament decided to work together, rather than divide the vote, the BJP would find it much harder to win a majority in 2024.

How convenient that the judge in Surat was replaced just before Modi's arrival, and the new judge was willing not only to revive the case, but also to deliver a guilty verdict in under three weeks. And how convenient that the two-year sentence the judge imposed is the minimum required to disqualify a lawmaker from parliament for an additional six years.

The BJP was all too eager to implement the verdict: within 24 hours, the Lok Sabha Secretariat declared that Gandhi was no longer an MP, and on the next working day, he received a letter instructing him to vacate his government bungalow. But Congress politicians smell a rat, with many suggesting that the verdict resulted not from due process but from a deliberate decision, taken at the highest levels, to silence him until well after the next general election.

Gandhi has, of course, filed an appeal, and if the court should grant him a stay of conviction, even the disqualification will have to be reversed. In that case, he could return to the fray, on the streets and in parliament, with his image burnished as the stalwart the government tried to silence. Buoyed by public sympathy and enjoying the enthusiastic support of an energised Congress, Gandhi could prove a much bigger thorn in the BJP's side than he was just a few weeks ago.

Already, the judgment has galvanised India's opposition. Regional parties that traditionally oppose Congress in their states – including the Aam Aadmi Party in Delhi, the All India Trinamool Congress in West Bengal, Samajwadi in Uttar Pradesh, Bharat Rashtra Samithi in Telangana, and the Communist Party of India (Marxist) in Kerala – have expressed support for Gandhi. They seem to have realised that they, too, could find themselves being picked off by a vengeful government. As the adage goes, "United we stand; divided we fall."

A more united opposition would be bad news for the BJP, which holds 60 percent of seats in parliament, but won just 37 percent of the vote in the 2019 elections. If a majority of the 35 other parties in parliament decided to work together, rather than divide the vote, the BJP would find it much harder to win a majority in 2024.

Some cynics suggest that none of this scares the BJP, because it is playing its own elaborate game to push Gandhi to the forefront of the opposition for the next election. A "Modi versus Gandhi" race, the logic goes, is one the BJP is sure it can win. But building up a major rival is an extremely high-risk strategy, which a party that is comfortably ahead in the polls – as the BJP currently is – is unlikely to pursue. The Gandhi debacle looks, instead, like a political own-goal.

But the stakes are far higher than one man, one party, or even one election. As we wait for the curtain to open on the next act in this political drama, Indians should be asking themselves whether democracy benefits when the principal leader of the main opposition party is jailed and denied a voice in parliament for anything less than truly criminal malfeasance? The answer for many – even those who do not like Gandhi or support Congress – is that it does not.

Safeguarding democracy requires ensuring a level playing field for all. What happens to Gandhi, thus, has important implications for India's future. One can only hope that Indians' commitment to representative government will prevail.

Shashi Tharoor, a former UN under-secretary-general and former minister of state, is an MP for the Indian National Congress.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments