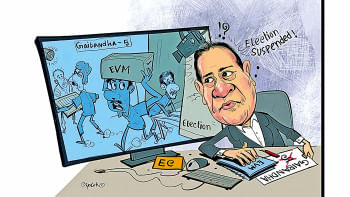

Election Commission's burden of a looming non-inclusive election

A longstanding political crisis surrounding the 12th parliamentary election has unsurprisingly transformed into a violent conflict. As this crisis deepens and widens—with increasing collateral loss of lives, properties, political and governance values, and public morale—where it may lead us is anyone's guess, except that the scope is expanding incessantly for a stronger foothold of undemocratic forces.

As unbearable as things are for the common people, and as ominous as they seem for the future of democracy, all rituals appear nearly completed by the Election Commission (EC) to move ahead with an election that is likely to be anything but inclusive. This conclusion can be drawn from the repeated assertions of our chief election commissioner (CEC) that what matters is the election, rather than who participates in it or does not. If or when such a facade of an election takes place, there will be no shortage of statements of success and satisfaction by the EC, which will be in tune with those whose design it has been to sustain the monopolistic capture of Bangladesh's political and governance space.

The EC is not the sole authority for ensuring free, fair, inclusive and credible elections, expected to be delivered in sync with the commitment and collective effort of the election-time government (ETG), law enforcement agencies, administration, political parties and other stakeholders like media and civil society. But in the EC's hands is undeniably vested the most crucial and strategic role. The question is whether the EC can unburden itself of the implications of a non-inclusive election.

When the CEC said, during the November 4 meeting with some political parties, that the EC has no mandate to resolve the political crisis, he may have been partially correct. The build-up of the political crisis, including its violent side, was designed by all actors involved in the zero-sum game of politics, where election and related activism are about a guaranteed stay in or ascendance to power. The crisis must therefore be resolved by those who have designed, and fueled it, namely the political parties and their powerbase institutions and agencies. And these do not prima facie include the EC. But the question is: has the EC played its due role, which could have prevented the crisis? Or have its actions—or rather inactions—contributed to it?

When the CEC asserts that the commission has nothing to do if some parties do not participate in the polls, he is not only self-contradictory, but also grossly wrong. Not so long ago, he clearly stated that if any of the major political parties do not take part in the election, it will lose credibility. At another event, when talking to international media, CEC Habibul Awal said that without the participation of BNP, the election will be incomplete. Then again, while speaking to officials of the administration and law enforcement agencies, the CEC advised that it does not matter who comes or doesn't to the election; as long as the voters cast their votes, that itself will be a big success.

It is unclear whether the CEC's exclusive reliance on voter turnout represents a deliberate lack of understanding of the fact that, as crucial as voter turnout is, creating a level playing field for a free, fair, and inclusive election is a sine qua non of voter confidence. If, however, the design includes doctored turnout rates, it is of course a different ball game.

In its September 2022 work plan for the 12th parliamentary election, the EC placed "inclusiveness"—defined as "active participation of all registered political parties"—highest on the list of its election objectives. On top of the list of challenges was the creation of trust within political parties for the election-time government and the EC itself. More importantly, the commission also committed that it would make appropriate recommendations to the government, particularly to ensure unrestricted participation of all political parties in the election. But all it has done in this regard was calling upon all political parties to participate in the election.

The EC has clearly bypassed the key mandate and responsibility of holding an inclusive election, which it had determined as the highest priority in its work plan. The frustration around the EC's inaction on this critical issue is accentuated by the fact that the commission takes pride in having made a set of recommendations for legal amendments to the government, which were adopted in parliament, even though some of the changes are widely considered to have curtailed the commission's own authority. These include the repeal of the power to cancel the election of a whole constituency. But, as the EC claims success in persuading the government to amend some laws, why has it refrained from recommending other more crucial legal changes that could ensure a level playing field for political parties during and before the election?

In particular, why did the EC fail to propose to the government (and other stakeholders) legal changes that could address key issues around the neutral, non-partisan, and conflict-of-interest-free role of the ETG? Why—beyond open-ended, agenda-less, and practically ritualistic "invitations" to the political parties—did the EC not present a set of proposals for legal changes to help achieve the most important objective of an inclusive election (as identified in its own work plan)?

The EC may want to face the mirror to ask if it has met the standards it had set for itself, and whether their actions have appreciated its value for its own credibility. It could at least be on a stronger moral footing by trying to address the crucial issue that was well within its jurisdiction and work plan. Instead, our election commission will now have to assume the responsibility of a non-inclusive election and the unpredictable consequences thereof.

Iftekharuzzaman is the executive director of Transparency International Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments