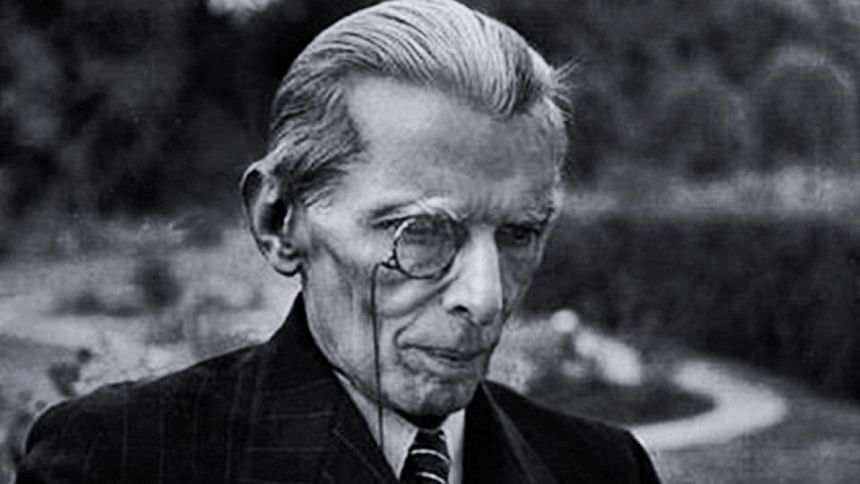

Was Jinnah the real villain in the story of partition?

On June 3, 1947, Lord Mountbatten, the last viceroy of India, announced his plan for the partition of the subcontinent—in particular that of Punjab and Bengal. This plan gave birth to two independent states: India and Pakistan. Many historians would like to emphasise that it was the determination and obstinacy of Muhammad Ali Jinnah that were primarily responsible for the cataclysmic partition, and the attendant huge loss of lives and properties. They would like to portray him as the sinister villain who expedited the horrendous partition.

There is, however, another view which says Jinnah never really wanted partition, and that the Muslim League reiterated the Pakistan demand as its ultimate goal only to save face. Historian Asim Roy says, "Jinnah was willing to accept something less than what almost everyone else knew as Pakistan." There is another view, according to which Jinnah was under the mistaken assumption that the Congress and the British would never accept partition. Therefore, when in the end Congress accepted partition, Jinnah was beaten in his own game of wits. Roy adds, "It was not the League, but the Congress who chose, at the end of the day, to run a knife across Mother India's body."

It would not be irrelevant to point out that Jinnah floated the idea of Pakistan as a "bargaining counter," but the fact remains that he did not have the bargaining autonomy once the mass mobilisation campaign began in 1944 around the emotive symbol of Muslim nationhood. This assertion of nationhood did not become a demand for exclusive statehood until the late summer of 1946. The Pakistan movement had started embracing a wider public from a much earlier period; once the communal riots started, the campaign only reached the point of no return.

The colonial British government may have created a Muslim community in its own image and allowed to transform a segmented population into a "nation" or a "juridical entity," but that did not mean that the Pakistan movement lacked popular support, at least during the last years of the British Raj. The popular aspects of the partition history cannot be lost on any discerning mind. The movement for Pakistan was mass-based and democratic. The politicisation of the crowd along communal lines was manifest. Historian Joya Chatterjee says the Bangalee "bhodrolok" launched a campaign for partition and sought to involve the "non-bhodrolok" classes as well. The Pakistan movement, therefore, could not be described as the sole handiwork of Jinnah.

The "surging waves of Muslim communalism" since 1937 had its roots in the long-term failure of the Congress to draw the Muslim masses into the national movement. The Congress admitted its failure and accepted partition "as an unavoidable necessity in the given circumstances." Historian Sumit Sarkar says, "The Congress leadership, instead of going for a mass movement, accepted this tempting alternative of an early transfer of power, with partition as a necessary price for it."

Historian Ayesha Jalal is of the view that the Lahore Resolution, which neither mentioned partition nor Pakistan, was Jinnah's tactical move, his bargaining counter to have the claim of separate Muslim nationhood accepted by the Congress and the British. The ideal constitutional arrangement Jinnah preferred for India was a weak federal structure, with strong autonomy for the provinces, with Hindu-Muslim parity at the centre. His optimism was that the Congress, keen on a strong unitary centre, would ultimately concede his demand to avoid his more aggressive scheme of separation, which "in fact he did not really want."

If we trace his early political career, we will find that Jinnah, in 1904, refused to be drawn into any controversy over the issue of forming a separate political body for Muslims. "Jinnah remained committed to his three-piece suits, his lorgnette, his cigarette holder and the king's English. No Gujarati for him and no political language that invoked religion." He saw Congress as his adversary and his nemesis. It was Congress versus the Muslim League, the two parties contending for power in an independent Indian state, that led to partition.

Jinnah's opposition, which later developed into almost hatred, remained focused upon the Congress leadership. His opposition was not against Hindus or Hinduism, it was the Congress that he considered as the true political rival of the Muslim League. During the last years of his life, Jinnah was both a self-avowed and the actual political leader of almost the entire Muslim community of undivided India. He had started his political life as an early champion of Hindu-Muslim unity, along with a total commitment to calls of freedom from the British rule. During that period, he stood unambiguously for a united India.

Muhammad Nurul Huda is a former IGP of Bangladesh Police.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments