Debunking Bose's Myths

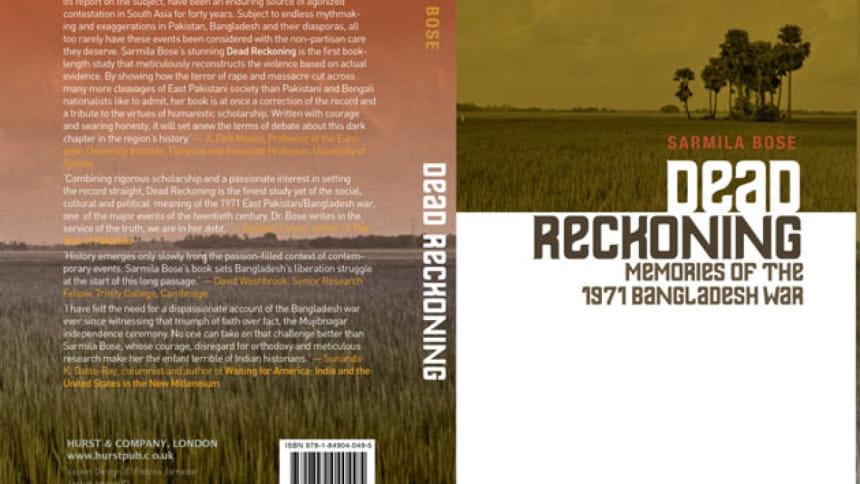

Dead Reckoning: Memories of 1971 Bangladesh War (2011) appears to be shaded by unrealistic assumptions, preconceived non-factual notions, myths and an unclear agenda. There is also a severe deficiency of clarity. In this context, I would like to highlight the following points with the hope that the author, Sarmila Bose, would revise her book based on a factual analysis of what really happened.

In the book, Bose mentions that Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was simultaneously "leading public incitement and private negotiations for power". This statement reflects the writer's lack of knowledge of the ground realities at that time, especially after the 1970 elections. Despite Bangabandhu's landslide victory in the 1970 elections, the Pakistan military government was resorting to unfair and unethical tactics to avoid handing over power to him. Bangabandhu tried to proceed through the constitutional process, which is why he participated in negotiations not only with the authorities but also other political parties having representation in the new National Assembly that was never convened. Side by side, given the massive confidence reposed in Bangabandhu by the people and the growing resentment due to delay and intransigence in transfer of power by Pakistan to the elected representatives, there were protests all over the country.

While describing the events from March 1 to 25, Sarmila Bose refers to what she calls "lawlessness and chaos" and functioning of what she terms as a "parallel government". Could she fathom the extent and magnitude of repression by the Pakistani military regime during that time? The author fails to distinguish between a peoples' movement based on democratic strength and quest for establishing constitutional legitimacy on the one hand, and on the other, the arrogance of a ruthless martial law administration and its violent response to the legitimate demand for transfer of power to the elected representatives. The government of Yahya Khan lost every legal and moral right to govern East Bengal after the 1970 general elections. There was no functional and constitutional alternative for the Bengalis other than to ensure compliance of instructions given by Bangabandhu. So what the author calls a "parallel government" was actually a government that carried out the instructions of Bangabandhu, the rightful leader of the Bengal. That was the only mechanism to ensure critical service delivery programmes continued in the country.

She refers to the Bengali nationalist movement leading to freedom as "proud, militant and chaotic". This reflects her inadequate knowledge of the milestones of our nationalist movements and struggle for ultimate freedom. I would ask the author to kindly trace the history of Bengali nationalist struggle that started after 1948 when Muhammad Ali Jinnah announced Urdu as the only state language of Pakistan. Further to the instant protests in 1948, Bengalis shed blood on February 21, 1952 to establish Bangla as the state language. The sweeping victory of Jukto Front in 1954 and subsequent movements to ensure constitutional rights as well as to resist political subjugation and economic deprivation bear credible evidence that the struggle for freedom progressed through relevant and appropriate phases that eventually led to the emergence of independent, sovereign Bangladesh.

Regrettably enough, the author refers to our historic War of Liberation as a "civil war". This is a shameful part of the discourse that falls short of facts and reason. It fails to assess the contents of a full-fledged war of liberation and tries to dilute its importance, inevitability, significance and outcome. Is there any need for a debate on the parameters that distinguish a full-fledged War of Liberation from a "civil war"? How would she look at the liberation movements in different regions that saw the emergence of states, especially in the post-World War II era? She has tried to undermine the struggle of a valiant nation for freedom. This gross misinterpretation and misrepresentation of facts erode the possibility of even the slightest degree of acceptability of her findings.

The book remains vague on the details of the atrocities committed by the Pakistani occupation forces. What the Pakistani forces and their agents did from March till December 1971 clearly meets the definitional and functional classification of genocide by the United Nations, as well as the criterion for genocide as applied by International Criminal Court.

The author has highlighted only selected military actions of Pakistan and overlooked the key dimensions of genocide. Sadly, she has fabricated theories to suit her interests and tried to downplay the widespread and barbaric acts of genocide, rape, arson, and planned ethnic cleansing by the Pakistani occupation forces. There is ample evidence of mass killings and destructions provided by scholars and historians and validated through international documents and global media. Even some authors from India and Pakistan have recorded their findings that confirm the occurrence of genocide in East Bengal in 1971. As regards her view that minorities fled across the border "not due to atrocities by Pakistani occupation forces but threat and torture by majority segment of the population", this is a gross distortion of facts and massive deviation from historical truth. Bangladesh has an impeccable track record of communal harmony and social togetherness, and this has been a key strength in Bangladesh's social setting for centuries.

At one stage, Sarmila Bose has questioned the relevance of calling Pakistan army "occupation forces." The truth is, as any historical review and assessment would suggest, after the declaration of independence by Bangabandhu, Pakistan as a state had ceased to exist and Bangladesh emerged as a sovereign independent state. Some documents confirm that after the historic March 7 speech by Bangabandhu, Bangladesh became independent and free from Pakistan rule. Both in de facto and de jure terms, Pakistani forces had no basis to stay in Bangladesh from that time onwards and the term "occupation forces" rightly describes their presence and activities.

Bangladesh's Liberation War was one of the most historically important instances of "people's war" against occupation forces. In 1971, people from all walks of life coordinated closely with the freedom fighters as well as people's representatives participating in the war. Bangabandhu's leadership and instructions and the responsibilities undertaken by the Mujibnagar government-in-exile carried the war to the final victory.

In view of the above, I would like to request the author to revise her book to replace the untrue reflections and motivated myths. If you have a story to tell, make sure this is the story of the people, the story of reason and truth. If you like to explore facts, you need to study with an open mind and ensure intellectual integrity. Please come up with a revised, logical and historically valid document that would highlight the great struggle of the people of Bangladesh in achieving freedom.

Dr Mohammed Parvez Imdad is an economist and policy and governance analyst currently based in Manila, Philippines.

Email: [email protected]

Comments