Bidyanondo and the battle for our soul

Are You Hindu or Muslim?

Who asks?

Helmsman, Tell Them:

A Human Being,

My Mother's Child, is Drowning!

— Kazi Nazrul Islam

The voluntary organisation Bidyanondo is a stirring example of what amazing things goodwill can achieve. It's youthful founder, Peru-based Kishore Kumar Das, has a richly deserved, devoted following of millions.

This is what makes the recent vile, sectarian attacks on Das so extraordinary. The attack has exposed the ugly underbelly of majoritarian bigotry in Bangladesh. It's also a call to action.

In moments like this we are presented with a poignant, existential question of national identity.

Just who are we?

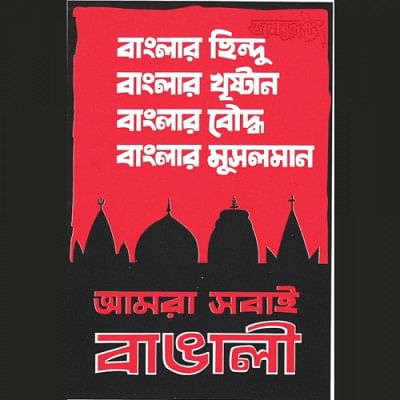

Didn't the 1971 Liberation War settle the issue? An official Bangladesh government poster said it all. With a mosque, church and temple silhouetted in the background, the poster declared unequivocally in Bangla: "Bengal's Muslims, Bengal's Hindus, Bengal's Christians, Bengal's Buddhists, Bengal's Muslims—We are All Bengalis."

Apparently Das's detractors failed to get the memo.

Reality is a lot murkier and messier.

Bengali Muslims appear confused and divided about their identity. The rise of Muslim separatism resulted in East Pakistan in 1947. Yet in less than a decade, the Muslim League, the midwife of Pakistan, got thrashed in the 1954 elections. The Awami Muslim League became the Awami League in a predominantly Muslim region. In 1971, Bangladesh embraced secularism and accepted Rabindranath Tagore's "Amar Sonar Bangla" as its national anthem.

Case closed?

Not so fast.

After independence, support for an extreme, intolerant form of Islam has grown. Infusion of petrodollars and a willingness of major political players to mollycoddle sectarian prejudice has contributed to this dreadful tendency.

The attack on Das is the latest example of this virulent prejudice. There have been other attacks.

I was outraged when Liton Das, the swashbuckling Bangladeshi batsman, was hurled with abuse simply because he had offered puja greetings on his Facebook page.

These attacks are an ongoing battle to define what being a Bangladeshi Muslim means. You could be a Muslim like my now-deceased mum and sister who pray five times and love Rabindra Sangeet. Or you could be the sort of Muslim whose faith has curdled into such vicious intolerance that Bengali culture, language can be anathema, and non-Muslims offensive.

Nor does religious practice necessarily precede prejudice. Mohammed Ali Jinnah ate pork and drank whiskey, yet he believed Hindus and Muslims were separate nations. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib was a practicing Muslim, yet he championed an inclusive nationalism that embraced Bengalis of all faiths.

Devout believers—of whatever religion—will have you believe that religious texts, whether it's the Quran, Hadith, Bible or Manusmriti—define their values. Don't you believe it. A society drawn from the same religious tradition can vary widely: It can be obscurant, bigoted and viciously intolerant. Or it can be humane, inclusive, and plural.

Take the experience of 12th century Jewish philosopher and physician Maimonides. He was born in Cordoba, Spain, at the height of the rule of the Muslim Moors, where he grew up in a flourishing Jewish community. However, when the Almohads, Berber Muslims, toppled the Moors, Jews were given a choice: conversion to Islam, exile or death. Maimonides chose exile, and eventually became the court physician to Kurdish Sultan Saladin, the great Muslim Crusades hero.

Can Muslim societies leave religious intolerance behind and embrace a humane, inclusive ethos?

The west has, despite its vicious history of intolerance. Amartya Sen astutely observed in a 2001 article in The New York Times: "When Akbar was making his pronouncements on religious tolerance in Agra, in the 1590s, the Inquisitions were still going on; in 1600, Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake, for heresy, in Campo dei Fiori in Rome."

In Bangladesh, the firestorm of protests following reports of bigoted attacks on Das included many outraged Muslims. This already appears to be having a salutary effect.

Mass public disapproval has been effective before. On April 14, 2001, Muslim extremists bombed Chhayanaut's traditional musical celebrations of the Bengali new year. (This is deeply personal for me. My sister and brother-in-law were performing.)

If the idea was to scare off people, it was an abysmal failure.

In years since, huge (overwhelmingly Muslim) crowds have thronged Chhayanaut's celebrations. Every year, clerics threaten participants in the beautiful mangal shobhajatra, a Bengali new year rally, with fire-and-brimstone speeches. Each year their speeches are treated with the disdain they deserve.

To provide the coup de grace to Muslim extremists, what's needed is what Herbert Marcuse called an "immanent critique"—effective criticism from within.

I've heard any number of devout Bangladeshi Muslims bitterly complain about how extremist Muslims give Islam a bad name. Well, it won't do to just talk the talk. Are you willing to walk the walk?

If you think bigots should not get to define your faith, then stand up for your beliefs.

It is only when practicing, devout Muslims stand up for their faith and confront the bigotry and intolerance that they so abhor will they achieve a Muslim society that reflects the tolerance and humanity they aspire to.

It took centuries, but it happened in the west. It can happen here too, but it won't happen without a fight.

There is no false choice of being Bengali or Muslim. Many Bengali Muslims proudly and joyfully embrace both. (If your orthodox Muslim views preclude music, that's your privilege, too. Just don't ram it down other people's throats. And respect the fact that national identity is defined by geography, not religion.) This will make for a better, inclusive, world.

"The main hope of harmony lies not in any imagined uniformity, but in the plurality of our identities, which cut across each other and work against sharp divisions into impenetrable civilisational camps," Sen wrote in "A World Not Neatly Divided," the aforementioned article.

Ashfaque Swapan is a contributing editor for Siliconeer, a monthly periodical for South Asians in the United States.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments