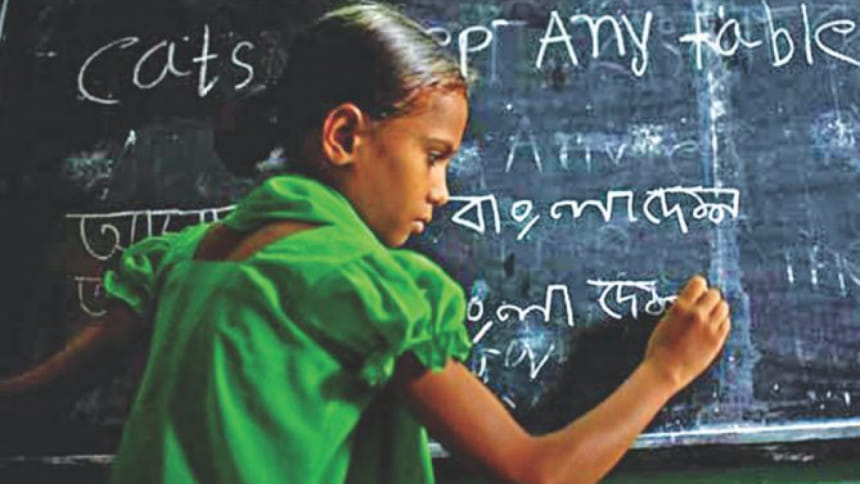

How do we help the youth of Bangladesh?

I met a girl last week who came to me looking for work. She was young, perhaps 17 or 18 by the looks of it, so I promptly did my duty, telling her that she should be in school, not working, though I knew very well this was probably not an option for her. She explained that she had a four- year-old son whom she had to support which is why she had come to Dhaka in search of work. Her mother would look after the boy while she laboured in near slave-like conditions to send home some money. She explained that her father had died four years ago, when she was pregnant, and the family had sold off their tiny plot of land, which is all they had left after the river broke, to pay for his treatment, though it did not save him in the end.

I asked what happened to her husband. She explained that since her father died, they could no longer make monthly instalments to pay the due dowry so he left her and remarried. She hastened to add that she didn't like him anyway; he used to beat her incessantly. Her father, she explained, was a day labourer, so he had married her off at the age of 11, in the hopes of reducing the burden on himself of feeding his four children. She said that's when she dropped out of school, and added that her school friend Ishita was still in school, now in grade nine. She added wistfully that she was a better student than Ishita, but Ishita still had her father to look after her expenses.

I asked about her siblings. She explained that they had raised Tk. 3 lakh from neighbours and friends, loans that would have to be repaid over time, to fix her brother a passport and visa for a job in Malaysia. I asked what skills he had. She said none. I warned her that labourers in Malaysia were often abused (and sexually exploited) and suggested that he enroll in a vocational training institute before going abroad; I even agreed to pay. She shrugged and said, they had already paid the dalal (middle man) and her brother was leaving by the end of the week. She said he was useless anyway, not interested in studying, and it was time that he man up and face his responsibilities, because he ought to take care of their mother, since she had a little baby to care for. I nodded, aware of the indulgent nature of men who have women to take care of them, and said, perhaps it was better that he eke out a living and face his responsibilities. She said it wasn't really his fault, he was a bit of a bolod, by which I understood he probably had some mild mental disability. I made the mistake of asking how old he was. She answered, 13. This broke my heart and I nearly couldn't go on with our conversation for a moment.

She saw my grief and added gently, that there was still hope for her family, because she was supporting her younger sister to go to school. Her sister, 12, would be married off (and raped) if she didn't pay for her school, because her mother could not afford to keep her. I realised then that this brave soul before me had to choose between selling off her brother or her sister – not an easy choice.

Within her five-minute introduction, I had already learned that she was a victim of child marriage, she was going to be exploited in illegal child labour if she found a job, and her child would suffer from malnourishment if she didn't, her mother was a widow, her family was driven deeper into poverty due to lack of access to affordable health care and natural disasters. She was domestically abused, partially due to dowry, and her mother-in-law put her to work after marriage. Poverty had forced her out of school and sent her brother off to face unknown challenges as a migrant worker. These are typical conditions faced by some 30 million people in our country.

Empowering people with skills can pave the way for them to climb out of poverty. The National Skills Development Policy, which has recommended a five percent quota for people with disabilities and a 10 percent quota for women, is a step in the right direction. Numerous donors have also entered the skills space, alongside government technical vocational training institutes, to equip the poorest with skills.

Social protection programmes meant to support poor people should partner up with training institutes to ensure that youth from destitute families, who can no longer afford school, receive technical training so they are able to earn fair wages and resist the pressure to get married or be exploited in dark, dangerous and dirty jobs. Local government representatives and youth volunteers should collect data on the poor families living in their areas to ensure that these young people are identified and supported.

Breaking the intergenerational transfer of poverty is a must if we are to achieve zero extreme poverty by 2021 as the Honourable Prime Minister has envisioned. All members of society could take some part of the responsibility to ensure that our children are given a fair chance to live a good life.

The writer is the Head of mTracker.co, the livelihood tracking wing of mPower Social. She may be reached at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments