Why do all developed countries want more inflation?

A recent headline in The Daily Star announced that the inflation rate in Bangladesh rose by 0.13 percent in March as compared to February this year, and on an annual basis went up from 6.14 percent to 6.27 percent. The slight uptick in the rate of inflation should not give the average consumer any cause for concern. Even economists like us grew up with the knowledge that inflation is bad and sustained periods of high inflation can wreak havoc on the economy.

The 1980's, when inflationary pressures in all major countries of the globe reached an all-time peak and often coexisted with stagnation in GDP growth, we saw coinage and popularity of the term "stagflation". In recent years, inflation has been less of a headache in almost all countries, except for a few economies on the fringes like Zimbabwe and some South American countries. However, in recent years, economists and central bankers are battling a new type of price behaviour trying to rear its head: deflation. But, many would ask, if inflation is bad, why can't we embrace deflation with open arms, since falling prices, particularly for gas and other petroleum products always seem to herald good times for the average consumer?

First of all, it must be told that not all countries are in the same boat. Inflation in Bangladesh in the last decade averaged 6 percent and currently there is not any expectation that it would overshoot, or undershoot the band that the rate has been confined to since 2002. Second, inflation, like many other economic variables, can be steered in the right direction, within some limits, but it is often not so. In the last two decades, it is estimated that while in developed countries consumer price index or CPI growth has averaged 1.5 percent, the corresponding growth rate for developing countries is 5.6 percent. For most countries in the developing world, including our neighbours, central bankers and finance ministers often face the same dilemma, i.e. how to keep inflation under control as the public sector runs a huge budget deficit and prints money to pay its bills.

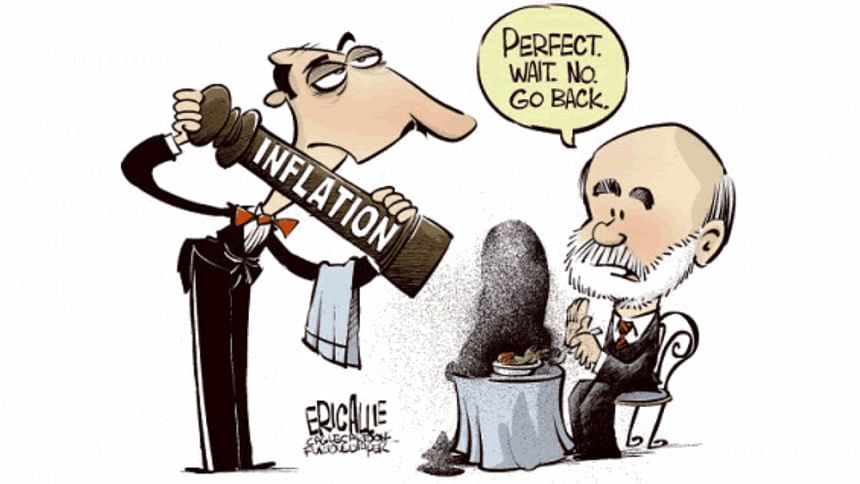

Ironically, for others, and particularly in the world's largest economies, the current economic problem is not one of inflation but of deflation or deflationary expectations. Many central banks, including ECB of Europe and the Fed of the USA, set a target rate of inflation which is around 2 percent. The target is what the central banks use to adjust monetary growth and other instruments including interest rate and reserve ratios. But, targets have been missed more often than not in recent years. One cannot open the newspapers or tune in to the world news without being aware of the unique struggles that the USA, European countries, and Japan are facing as the inflation rate starts to move either in the negative territory or hover very close to zero. CPI in the 19 countries that use euro has declined for three straight months since December - according to Eurostat, the statistical arm of EU - going down by 0.2 percent in December 2014, 0.6 percent in January 2015, and 0.3 percent in February 2015.

When the price index of a country decreases, i.e. price drops across-the-board, it is symptomatic of a deeper malaise which may be either economic slowdown or a lack of confidence in the country's short term economic future. Deflation in some instances is also accompanied by prolonged period of declining wages and stagnating per capita income. The other worry is its stickiness and appears with other macro variables to be stuck in a low-level equilibrium trap.

Japan suffered from this plight in the 1990s and was beset by slow economic growth, sluggish employment, and low rates of investment. Recently, it appeared that Japan finally managed to be able to break away from the clutches of this stagnation-deflationary cycle, but in recent months the ghost of the 90's appears to have made a comeback.

Let me get back to the question I posed at the beginning: Why not let the price level go down and allow the consumers to enjoy the benefits of an increase in real income? After all, if the price of gasoline goes down, you pay less to fill up the car gas tank, and the extra money in your pocket then allows you to spend more on food or other necessities? But, there is the rub. First, there is no necessary link between lower price of gas and greater demand for, say, other commodities. Second, if prices of all commodities are going down, it might be symptomatic of a deeper malaise. Deflation often coexists and is caused by lack of jobs and a decrease in consumer spending on domestic goods. Thirdly, if prices are going down, business and households might adopt a "wait and see" policy in anticipation of even lower prices. Finally, falling prices cause the burden of borrowing, the "real rate of interest" to increase, and leads borrowers to cut back on investment. Thus, all this might lead to a deflationary cycle and keep the economy in recession.

So what are governments doing about it? To boost inflation, central banks can offer the same type of monetary stimulus that has been used by the USA and UK to combat unemployment and low growth in GDP. The Eurozone countries have struggled for almost two years with the "to be or not to be" mindset and finally ECB announced on January 22 its policy to use quantitative easing (QE) and pump more money into the economy. ECB is set to buy government bonds and other assets at a monthly rate of $67 billion with a goal to push the inflation rate to the 2 percent range. Japan's central bank announced on October 30 last year that it will strengthen QE by $730 bn. The US Federal Reserve System on its part has ceased QE but is hoping that the inflation rate will pick up before it raises the interest rate which it had kept close to zero in the last six years. Britain and China are also taking measures to counter deflationary pressures.

So, what can we expect in the future? The US economy is poised to accelerate and experience an inflation rate that is above the current rate but not over 2 percent that the Fed targets. ECB is more optimistic about the prospects of economic growth than inflation. Inflation, which it targets at 2 percent, will remain close to zero level this year, and increase to 1.5 percent and 1.8 percent, in 2016 and 2017, respectively. So for old-timers like us, it appears that the economic outlook we grew up with, i.e. stagflation is out. The "slow-growth, low-inflation" is becoming the dominant paradigm, at least in the short term.

The writer is an economist and often writes on public policy issues.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments