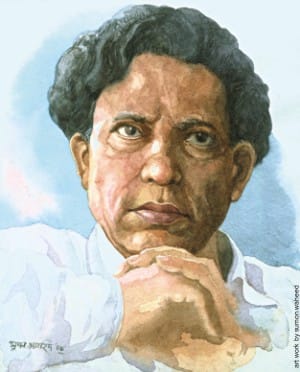

Salim Al-Deen

art work by sumon waheed

Last year was one of the most fruitful for Salim Al-Deen, whom I have been calling 'Salim Bhai' ever since we met in Sharif Mia's canteen at Dhaka University nearly some forty years ago. A driven, work-obsessed and rather tensed individual, although never without a sense of humour and an indulging attention to friends, he spent the year basking in public adoration, and creatively engaging himself with ever more challenging tasks. The year began with his receiving the Ekushey Award for his contribution to Theatre, a belated recognition that nevertheless, gave him immense joy. It was not Salim Al-Deen the state has honoured, he told me in reply to my congratulatory call, but our indigenous theatre - which he lived and died for, literally speaking. Throughout last year, he also received rave reviews for his latest narrative Shornoboyal, which the weekly 2000 published in its Eid issue as upakhyan, but which Salim called akhyan and many others called natak or drama or even novel. Confusion about its genre aside, Shornoboyal was a splendid piece of work - well-wrought, profound and passionate, with a language the Mongal Geeti writers would be proud of. Then there was Nimojjon, a stage play that his long-time comrade-in-arms Nasiruddin Yusuf Bachchu culled from a long and complex narrative. It was something like Shornoboyal but had a more global perspective, since its subject was war and the unspeakable things people do in the name of war. Salim Bhai and Bachchu formed one of the most productive and close-knit theatre teams that I've seen anywhere, and together they've given a rich trove of dramatic productions to our theatre - Kittonkhola, Keramat Mongal, Prachya, Hathodai, Joiboti Konyar Mon, Horgoj, Bonopangshul, to name only a few. Bachchu had an implicit understanding of Salim Bhai's thoughts and philosophy, his idea of theatre and, more importantly, how our own theatre should shape up. Watching a performance of Nimojjon a few months back, I marveled at the uncanny way Bachchu had sculpted the finished version out of a myriad of different plots and ideas and characters that crowded the seemingly endless narrative.

Sitting one evening on the sprawling roof of the old arts building of Jahangirnagar University - which housed the Drama Department Salim Al-Deen had founded and zealously guarded like a possessive parent - he told me what Nimojjon was all about, and frankly, my head went into a spin. The horizon in front of us was dyed crimson by the setting sun, which I felt best described Nimojjon's bloody mood. But Bachchu thought otherwise - he made the stage black-and-white, and pale and ghoulish, which Salim agreed was what the world has become after its cataclysmic nimojjon (drowning) in our time. Nimojjon, I may add here, is both a diagnosis of our current crises and a postmortem carried out on the cadaver of our civilization.

Salim Bhai's colleagues and students -- whom he treated as his children and addressed as tui -- decided to give him a reception for the Ekushey award. It was a huge and festive affair with the entire university, not just his department, turning up at the university's TSC auditorium. Salim Bhai had asked me, along with a few of his friends, to speak at the reception. I was astonished and touched by the intensity of passion his students displayed for him. Of course, I was not a stranger to such spectacle since I had on many occasions observed the highly-charged flow of feelings and emotions between him and his students, but that night was something special. After the event, a visibly moved Salim Bhai walked me to the car. We lingered a while as students crowded around us. His eyes glistened with tears as he hugged me. "Good night," he said, "and thank you for coming."

That too was uncharacteristic of him. He never thanked anyone with words - he always did so with a gesture or a smile.

That night was the last time he would speak so eloquently about his vision of Bangla theatre, and the tasks he had set out for himself. He seemed to be demanding at least a decade from the eternal time-keeper for him to finish his designated part, although, I suspect, he knew he was booked for an early exit, being the master dramatist that he was. Call it foreknowledge or premonition: an early whiff of mortality must have made him apprehensive, and rush through with the plans that had so long been forming in his head. I remember getting a telephone call from him a couple of months back. It was a reminder to set a question for an exam - a perennial duty (plus checking scripts, taking viva exams, etc.) thrust upon me by Dr. M. Muinuddin, his 'certificate' name. In course of our conversation he told me he had written a few songs, set them to music and was talking to a singer whom he thought had the ideal voice. "I am running against time," he told me, and hung up, as he often did, in the middle of a sentence.

That was the last time we talked. 'Running against time,' it seems, had more than one meaning. I took the literal meaning, while he had a metaphysical one in mind.

Salim Al-Deen's achievements are truly astounding. Almost single-handedly he revived the old, pre-colonial tradition of Bangla dramaturgy, enriched its repertoire by exploiting time-tested stagecraft and modes of presentation, blending modern sensibilities with indigenous skills of narration. If his Shakuntala suggests the presence of the Sanskritic tradition, Kittonkhola goes back to the Middle Ages, and assembles the narration, songs and dance traditions of medieval Bangla drama. This last was his field of specialization, and the subject of his PhD dissertation. He also wrote numerous television plays, setting a standard that has yet to be surpassed.

Time may have hastily drawn the final curtain on a performance where Salim Al-Deen, after a stellar performance, went out early, but went out in a blaze of glory, setting people thinking what a marvel he had been. As for me, I will miss his company, his enlightened talks, and the glorious evenings on that roof looking at sunsets and sharing thoughts that are the treasures of a lifetime.

Syed Manzoorul Islam is professor of English at Dhaka University.

It's a great shock for me to have to write a tribute to my dearest teacher Dr Salim Al-Deen so early. He was fifty eight years old physically, but mentally he was one of the most energetic and young person I've ever known. It is impossible to convey to readers the extent of his knowledge. Most people know him as a playwright only but he was also from head to toe a successful teacher, a creative moulder of students. The style of his teaching was unique and full of innovation. The Department of Drama & Dramatics at Jahangirnagar University was his brainchild, which came into being in 1986. At that time a majority of people dismissed the idea - 'it's a bogus department, 'drama,' can it be a subject for scholarly study?' By now it's been proved that Salim Al-Deen was absolutely right, and that despite all odds he had succeeded in establishing his dream, with his core belief that creative persons create a good and successful nation, with Greek civilization as the reference point.

The Department of Drama & Dramatics at Jahangirnagar University is one of the most powerful creative and communication departments in Bangladesh. The syllabus of this department is of a high standard and is upgraded regularly according to the demands of time. Salim Al-Deen and his team constructed it very carefully. The syllabus is divided into two parts: Practical and theoretical. In the Honors degree course every student has to do acting, directing and writing but in the Master's class they are free to choose to concentrate on any one of those: performance or direction or playwriting. It was a process designed to unleash maximum creativity.

Dr Salim Al-Deen was an unparalleled writer and creative teacher. His teaching methodology was unique. Through his teaching process one could locate one's inner creative eye. Salim Sir's teaching method can be divided into two parts: one, academic; and two, non-academic. The academic teaching process consisted of two further divisions: one was theoretical and other was practical courses.

In theory classes he used the lecture method but because of his personality and way of presentation, even hard topics became more interesting and students were hypnotized. There was no fixed time limit for his classes, and sometimes they continued for two or three hours. During a short break he would give money to a student to bring some snacks for all, and then would start again. Theory classes would take place in different environments: near the university lake, under trees, on top of the roof, in sunlight in an open space, etc. Drama is related to Life and Nature, he would tell us all the time, and which was why all the time Sir would attempt to link Nature and class lesson together for his students. Through his lectures he also linked the day's class topic with contemporary events, so that we students could incorporate into our class work our experience of real life. Sometimes he said jokes, made fun, to refresh our minds. We students had to be well prepared to be able to communicate with him and understand Salim Sir's theory classes.

In the practical classes our creative professor was a practical, hands-on teacher and used participatory method. He was not only a playwright but also an excellent stage director, whose successful academic productions were Ekti Marma Rupkotha, Dewana Modina, Meghnadhbodh Kabya, Ujane Mrittu, Kado Nodi Kado, Horgog etc. From the Greek to Bangla drama, from Stanislavsky to Peter Brooke - Salim Al-Deen synthesised every method and presented it in his own way. To prepare an actor he used very many theatre techniques which were exceptional and related to the overall production design. Style of acting, costume design, choreography, music, dance, rhythm, sound effect, in every segment of theatre, in all its constituent parts, Salim Al-Deen was a specialist. He himself would demonstrate every physical movement: he did not hesitate to sing and dance with his students. The physicality of acting, the movements of the body, was his first priority since he always emphasized that stage drama acting was different from visual media acting - that by very definition it should be more 'theatrical'. Traditional Bangla acting style was transformed into its modern form by Salim Sir. He also consistently tried to use simple and available local materials to design production sets. I remember in the production of Marma Rupkotha he used only bamboo sticks to create scenarios such as rainfall, door of heaven, etc. In Ujane Mrittu he used only black-and-white cloths to show the dark and white side of life.

Salim Al-Deen explored, and comprehensively taught us, many theories of modern drama, such as 'Narrative style of Bangla Natto,' 'Comparative Drama Studies', 'Fusion in drama' and 'The Integra list Theory' (Doito Odoito Badi Totto). Through all his theories he tried to prove that we Bangalis have our own dramaturgical tradition that is independent, and separate from, Western drama tradition and practice.

The non-academic aspect of his teaching were simple walks during mornings and evenings - conducted by him, with even students from different departments joining in. During these walks he expounded on Nature, its sound, on trees, birds, butterflies, and especially the relation between Nature and living creatures. This way the total campus and the environs of Jahangirnagar University became the classroom of Salim Al-Deen's non-academic lectures and tutorials.

We later entrants always felt that the first batch of students of the department were so lucky since they were closer to him. Sir treated them as his own children. Year after year the department expanded and Sir became the most senior teacher. Since he took the senior-most classes, he worried that it would create a generation gap between teachers and students. That development, he thought, would not be good for the department. After I joined the department as a teacher, he took me aside and said, "Ribon, be close with your students, sit with them by roadside tea-stalls and talk with them. Take care of their personal problems too."

So many students shared their personal problems with him and he tried to solve it; in this way he became in an overarching sense Guru, Shilpo Pita, Guide, Philosopher and Lover. To me, simply put, he was my Baba (father).

I say to him now, wherever he is, and I am sure he is listening: "My Baba, I miss you very much. We (Ribon, Akash, Anusrita) will miss you at every moment of our lives."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments