The Mosquito and the Ear

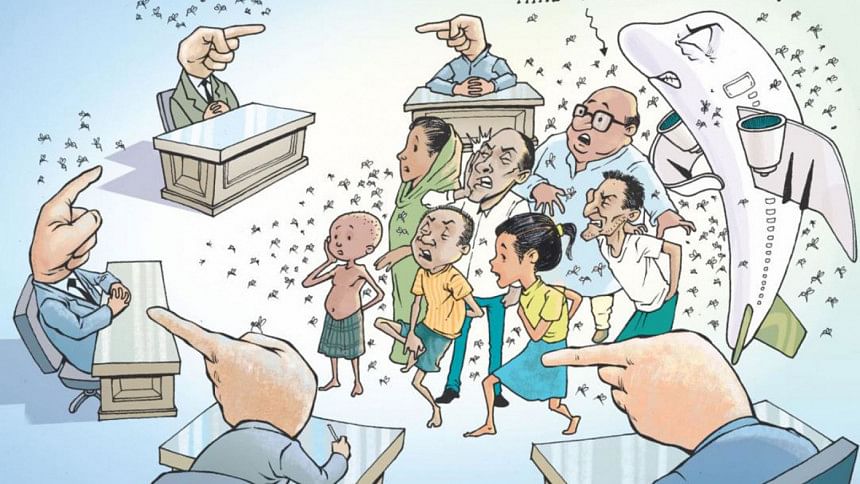

There used to be a TV advert in which a husband was rebuked by his judgmental wife for not being able to kill even a mosquito that was sitting on her cheek. It was the silliest of jobs that the husband had failed to perform, and the taunt confirms the fact that while male mosquitoes are useless, only female mosquitoes bite. Jokes apart, the ad would probably hurt the male egos of our city fathers, and their predecessors before them. They know all too well that killing mosquitoes is no mean task. As I type lying under my mosquito net, staring at the scores of tiniest blood-seeking creatures crawling above me, I am visited by the frustrated outburst of a former mayor who, at the outbreak of chikungunya, notoriously said that he couldn't go inside people's mosquito nets to kill them. I share similar helplessness against this primitive enemy even in an age when men are sending drones to Mars. My frustration is deepened by the knowledge that we are yet to modernise our mosquito-fighting strategies.

Humans have been waging a war against mosquitoes for centuries. The war reached military proportions since the epidemiologist Sir Ronald Ross, affiliated with the British military, proved the role of Anopheles (translated as "useless") in malaria and US army major Walter Reed made a similar discovery about Aedes (translated as "unpleasant") and yellow fever.

When we were growing up, we used to see airplanes being used for aerial spraying to kill mosquitoes. Back then, the low-flying aircraft, specially converted to spray insecticides, was a source of immense joy and excitement. It created an atmosphere of total war against the tiniest of insects. The aerial attack would be followed up by foot soldiers in khaki dresses carrying heavy brass cylinders on their backs, undertaking targeted attacks in drains and bushes. They would even come inside people's homes to spray in areas where mosquitoes were hiding. Little did we care that such chemicals were harming other animals and the toxins were doing permanent damage to the environment. Yet it felt good to see that something spectacular was being done to address the mosquito nuisance. Then there were attempts to introduce larva-gobbling guppies in the drains, which turned out to be a project of pouring money into the drains. Then foggers were introduced to the arsenal of mosquito-fighting apparatuses that previously included only hand-held sprayers.

According to an old published report, most of the equipment of the city corporations are non-functional, if not out of order. Then there is this issue of not having enough people to operate the equipment. The efficacy and price of imported medicine have been a source of perennial complaints and controversies. Millions of takas are being spent to no avail. Explaining the inadequacy of their anti-mosquito drive, one city corporation staffer said that the loud-noise-making foggers could alert mosquitoes from a distance. While these machines could be good for adulticiding (controlling mosquitoes in their adult stage), they were not that effective against larva. The moment streets are strewn with fogs of insecticide, the insects seek shelter in the plants of our terraces or rooftop gardens. I guess regular warfare has turned into guerrilla warfare.

This is particularly true as mosquitoes are reputed for their uncanny ability to mutate and become resistant to pathogens (chemicals). Recently, cutting-edge molecular biology is using the nuclear technique to sterilise male mosquitoes or to rewrite their DNAs. In China, they have already applied such techniques with considerable success. Humans are now faced with a question: should they purposefully cause an entire species to go extinct? Many birds, beasts, flowers and fruits have disappeared due to our negligence, overconsumption, or invasion. Do mosquitoes deserve our ethical concern?

Humans and mosquitos have co-evolved. And we share the equal desire to prey on the other. Each year, more than a million people die of mosquito-related diseases. Our enemies are very sophisticated compared to the claps that we are equipped with. They have the sensory organs to decide who among us has the right nutrients for them; they have the drilling apparatus to penetrate our skin and find the blood vessels. And they have the resilience to constantly mutate and survive. But do they have the right to live?

When the European invaders annihilated almost the entire indigenous population of the Americas, they tried to colonise the space by suggesting that only the civilised ones had the right to live. They used to bill a poster to offer bounty for dead local people, saying, "the only good Indian is a dead Indian". By Indians, they, of course, referred to the misconception that Columbus landed in India where the inhabitants were "Red". In an inter-species contact zone, are we now to say, the only good mosquito is a dead mosquito?

I don't think anyone in our part of the world will disapprove. With dengue, zika, chikungunya and malaria still looming large, there is hardly anyone who would object to the total annihilation of mosquitoes. They are not only a nuisance but also a menace. They have the mythical reputation of subduing the mightiest of earthly lords. Nimrod, the Mesopotamian king mentioned in the Bible, was killed by a mosquito that entered his brain. His entire army was also killed by the swarming insects sent by God to avenge Nimrod's boastful attempt to equal the maker.

Now that humans have finally acquired the technology to eradicate the mosquito species, the Western world is pondering on ethical and environmental issues. They want to make sure that eradicating all 3,500 species of mosquitoes from the world does not harm the ecosystem. The research remains focused on public health as one of its primary sponsors is the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation that wants Africa to be free of mosquito-driven diseases.

Tales of the resilience of African mosquitoes are found in African folklore. In Things Fall Apart, the Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe recounts one such story in which a mosquito asks a human ear to marry him. The ear bursts into laughter: "How much longer do you think you will live?" the ear asks. "You are already a skeleton." Ever since, whenever the mosquito comes near the ear, it never misses the opportunity to remind the ear that it is alive.

This is the reason mosquitoes always seem to attack the ears. This is the same reason I am singing this old song to have the ear of someone powerful who will end the menace.

Shamsad Mortuza is Pro-Vice-Chancellor of the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (ULAB), and a professor of English at Dhaka University (on leave).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments