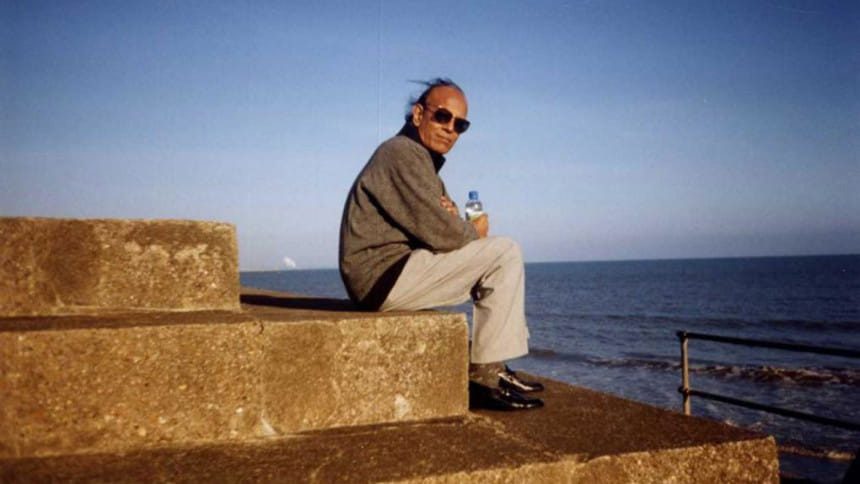

The intellectual journey of Khan Sarwar Murshid

In the black-and-white cultural milieu that often engulfs us, we are frequently unable to grasp a man's intellectual worth when neat categories cannot pin them down. But man is a many-splendoured being. I have tried to understand what had made the man, my father. I delved into family history, and in his activist and teaching roles. I knew him to be detached from any ostentatious show of religious affiliation, a man who questioned all assumptions and yet continued to search for moral order and spiritual certainty. For him, truth and beauty were integral elements of that quest. Intellectually, at one level, it led him to explore philosophy and study the great literary minds of the early twentieth century, both Eastern and Western. At another level, he came to appreciate refined culture, arts, manners, and etiquette. Gradually, he evolved into an aesthete.

An unexpected finding has enabled me to explore some of these dimensions of his intellectual world when I chanced upon his moth-eaten thesis with a letter of recommendation for its publication by his external examiner, Professor Bullough of the Department of English Language and Literature, University of London's King's College. Indian Elements in the Works of W.B. Yeats, T.S. Eliot and Aldous Huxley is now awaiting publication by the University Press Limited. The following ruminations follow from my many readings of the manuscript as I prepared it for its publication in 2020. I hope that my father will forgive me for this audacious task. Being a perfectionist, he only brought out one or two articles from this work. When he undertook this study, it was an uncharted field. It was many years later that the theme of Indian elements was touched upon by other scholars. The work remains relevant for us today because it touches on issues of moral responsibility, right conduct and social order.

What transpires are the musings of a young man navigating the crossroads where the great minds of the West meet those of the East. It required considerable courage for a young man to tell the Occident, in the immediate aftermath of the end of empire, that the East had exacted its revenge on the West. The western intellectual milieu had been changed forever.

Through this study, along with what we know of Murshid's life and other interests, we can picture the image of a more complex and nuanced human being than what we had supposed. It provides the missing link that helps us understand his own development better, for the impact of his study on himself had been no less profound than it had been on his subject matter: the intellectual worlds of Yeats, Eliot and Huxley.

We had always sensed that the Buddha had a special place in his heart: not only was the bust of the Buddha one of his two most cherished possessions, next to that of the ancient Greek goddess, Venus, but he had also lovingly called his first-born Gautam Firdous, after Gautama Buddha! But the manuscript reveals how that connection manifested itself.

Reading his literary treatise, it struck me that some of the basic values he sought to inculcate in us were, in fact, Buddhist in origin, particularly the ideas of sangha and moral responsibility. Young Murshid shared Huxley's idea that a minority of individuals can "attain enlightenment" and make a difference. His life and works came to embody that value. He championed the values of right conduct, followed a path of legitimate action in its defence, and sought the company of like-minded people in its pursuit. He painstakingly promoted the selection of suitably qualified persons for given tasks in the interests of an orderly society. His passion for teaching to train young minds in critical thinking was an aspect of promoting that ideal.

Like Eliot, Murshid was fascinated by the idea of the "Eternal now"; and like Yeats, the concept of the "unity of Being" exercised him. However, the Buddhist concept of anatman—that there is no soul, but there is rebirth—left a sense of uncertainty. Surely this is the only life we know, and this was the only life to be lived. Beyond death was the realm of the mysterious unknown. Like Rilke, he found it slightly fearful.

He identified most with Yeats. Both opted for a this-worldly approach to life, where love, beauty and delight have a place. Eliot and Huxley chose detachment but fell short due to their excessive loathing of the body and preoccupation with negativity, such as with "dung and death", possibly due to their traditional Christian upbringing centred around concepts of original sin and guilt. They missed the cue of the ancients that life is to be delighted in even as we separate ourselves from its attachments.

At the core of Murshid's world view had already evolved the concept of values. It included ideas of order and moral responsibility, justice and right conduct, truth and beauty as the measure of such an order. He summed these up in his concept of values. To him, values were what made a man, and those values are what held society together. He had already come to call these new values when at the ripe age of 25 years he began to publish a journal from Dhaka in 1949, called New Values, several years before he embarked on his spiritual journey into ancient Indian philosophy in the context of his literary studies. The influence of the Buddhir Mukti Andolana of the 1930's in Bengal can be traced to the secular appeal of the journal. Some may even venture to relate this stance to the values of the European Enlightenment. He had also explored other spiritual systems focussed on the Qur'an and Sufi thought, his interpretations bringing out their hidden wonder and depth.

With hindsight, it would appear that his intellectual pursuit for an orderly society based on the values of right conduct, truth and beauty found a spiritual counterpart in his quest to understand the nature of man's relationship with God. In essence, one could conclude that these two journeys—the intellectual and the spiritual—that compelled him to action all his life were one and the same. Notably, however, he was the living embodiment of the values he upheld and the world view he adopted.

Professor Tazeen Mahnaz Murshid is a social scientist and historian, and daughter of Professor Khan Sarwar Murshid, who died on this day eight years ago.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments