Woodsman, spare that tree!

Did not Joyce Kilmer say, "I have never seen a poem as beautiful as a tree"?

There was a time, not too long ago, when the metropolis of Dhaka was a veritable arboreal wonder, with multi-coloured flowering trees and hundreds of fruit-bearing trees and canopied avenues flourishing in every neighbourhood. My own University campus bloomed bright red and yellow and mauve, and each falgun was a riot of colours offering a serotonin rush of joy to the perceptive mind. Cognition was enhanced, allowing me the natural resource to "half-perceive and half-create", a phrase used by William Wordsworth to account for the autochthonous nature of the growth of the poetic mind.

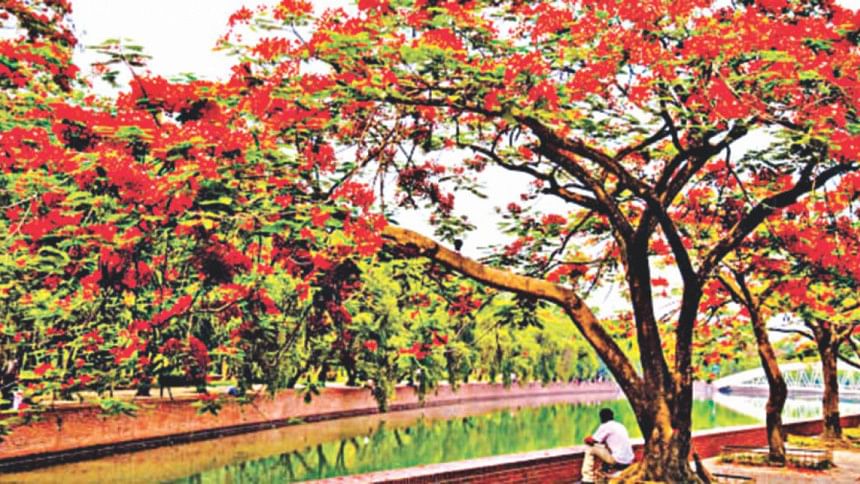

I remember walking in thrall to the beauty of natural efflorescence on the green spaces between the Arts faculty and the Central Library, and languorously indulging my peripheral vision to glide from one gorgeous treetop to another as I went to the Registrar's building on personal or official errands. I remember a time, lecturing weekly in a classroom with windows to the west, how the rich scarlet-laden branches of the krishnachura trees, vivid against the blue sky, inspired me, soothed me, and allowed me the grace and benediction of 'Inscape' to share with younger, eager, pliable minds.

This was a time when very important roads for very important people had not cut very ordinary me from a long and pleasant rickshaw ride all the way from the Staff Road railway crossing to Neelkhet. This was a time when a song would erupt, albeit silently in my soul, as I rode through Mohakhali and beyond, with the central line of flowering krishnachura guiding the lingering sight to the horizon. This was a quieter time, more mellow, more sane, more human, more humane.

I am thankful that one especially majestic tree still stands, protected by commemorative emotion and edict. This is my tree, for I am transported to a state of ecstasy every time I look up and blink at the transcendental beauty of the spreading foliage of the hundred-year old tree sheltering the Martyr's Memorial opposite the Vice-Chancellor's colonial-style palatial residence. I am completely and desperately in love with this tree. It defines me. It anchors my spirit to the core of my city.

Woodsman, spare this tree! Let this tree speak to you. Let its branches lift you up from the desire for desiccation and deforestation. Let its soft rustling leaves beckon you towards veneration for the living, breathing flora. Let its cool shade save you from the noxious fumes of gridlocked motorways. Let it offer you wisdom to curb your greed for brickfields and more brickfields to build concrete jungles of squalid, suffocating tenements. Listen to the voice of the tree: female, feminine, life-giver, fruit-bearer.

What does every sentient being need? Just a little breathing space, fresh dew on the grass, a little patch of open sky to gaze at the floating clouds or up at the myriad twinkling stars on a clear moonlit night. Literature makes emblematic use of nature's intimate connection with the animal world. I recall Shakespeare's precious pastoral retreat, his Forest of Arden, with Rosalind as Ganymede; arbour, arboreal, natural, enchantingly transformational, restoring order and sanity to human will and society. I recall the wounded Wordsworth seeking refuge in the lap of Mother Nature. He has his sycamore tree and the secure, nurturing enclosure of Tintern Abbey, offering recuperation in warm uterine embrace.

And we in Bengal have the Banyan tree; indigenous, iconic, iconographic. Alas! So few of these old trees, with their mystical tangled roots, remain. Rabindranath Tagore has immortalised the Banyan tree in his famous poem, and the connection between the child and the tree becomes an allegory of the intimate, inchoate bond between mankind and nature. Today, the child's plaintive cry echoes my own heart's yearning as I mourn the massacre of a million trees by the woodsman's axe:

O you shaggy-headed banyan tree standing on the bank of the pond,

Have you forgotten the little child, like the birds that have nested

In your branches and left you?

....He longed to be the wind and blow through your resting branches,

To be your shadow and lengthen with the day on the water…

The writer is Professor, Department of English, University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments