Food for sub-continental Muslims

Food plays an important part in all our lives, and in Islam, based on the teachings of the Prophet Mohammad (SAW) and the holy Quran, is a way of life, dietary guidelines are an important part of it. Verses in the Quran invite believers to study their bodies, souls and their mutual relationship. As the human body is the greatest gift of God, people are advised to take care of it. Islam prompts for a balanced and light diet in terms of quantity as well as nutrition.

The Arabic word halal literally means lawful, refers to food allowed for Muslims. Quadrupeds like cattle, sheep, goats, camels for consumption, along with chicken, duck, game birds, etc and all scaly fish. But apart from being halal, food must also be "zabihah," meaning slaughtered according to Islamic rituals. Slaughtering an animal according to these guidelines limits the pain it must endure. Vegetables, fruits, legumes like peanuts, cashew nuts, hazel nuts, walnuts, etc, are all halal, along with grains, such as wheat, rice, rye, barley, oats, etc. Milk, honey and any non-intoxicating plants are halal as well.

Haram refers to food that is unlawful—like carnivorous animals, pigs (and their by-products), birds of prey and those which do not have talons but flap their wings more often, reptiles and insects. In addition, haram extends to the method by which the animal has died, so those that have died instead of being slaughtered are haram. Similarly, halal animals killed in the name of anyone other than Allah are also haram. Alcohol and other intoxicants are most definitely haram.

Prior to the advent of Islam, Arabs had a very basic diet, with daily food including dates and either camel, sheep or goat milk, churned into butter and clarified for storing. Meat was a luxury; only gazelle or ibex were hunted. With the advent of Islam, the dietary laws laid down in the Quran began to be followed. Certain foods items are mentioned in the Quran, and are known to have particular benefits. Squash is among the vegetables mentioned by the Prophet, and dried fruits are endorsed in the Quran and Hadith. The Prophet also mentioned figs, saying, "If I had to mention a fruit that descended from paradise, I would say this is, because the heavenly fruits do not have pits… eat from these fruits for they prevent haemorrhoid and help gout."

The spread of Islam following the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 AD changed the tiny Islamic world. With revolutionary fervour, the Arabs from the Arabian peninsula swept into greater Syria and Persia, converting them into Islamic domains until they had established a vast Islamic empire right across Asia and North Africa and into Sicily and Spain. They took their culinary traditions with them and adopted those of the conquered territories along the way, so a myriad dishes and flavours permeated the empire.

The new Umayyad based in Damascus, was not known for its cuisine. Majority of the Arabs remained nomads, and knew nothing of agriculture; milk and dairy products remained their main diet. Milk was consumed warm, straight after milking, or thickened in a goat's skin – yoghurt was not introduced until after the conquest of Persia. Sometimes unleavened bread was made by grinding the grain in a stone quern, kneading it with a little water and shaping it into rounds. It was then baked on a metal dish, heated on dried camel dung or dried wood. Very little meat was eaten, and dates were a favourite.

However, some Arabian dishes, like harissa, became as famous and internationally known as pizza is today. This dish also travelled to England around the 14th century, where the name was translated to English as frumenty, Latin for "grain," and became a kind of wheat stew boiled with milk cinnamon, and sugar.

CUISINE OF THE CALIPHS

It was during the Abbasid period, from 8th to 12th century, that Islam was the most powerful influence in the world. The expansion of Islam caused the spread of food that was formerly known to only one region. Rice, for example, originated in India and was introduced to Iran and Syria. Not all foods, however, could be grown readily in every region of the Muslim world, and this necessitated trade.

The Abbasid kitchen was equipped with two main appliances – the tannur or oven and the mustawkad or stove. The tannur, used for baking, resembled a large overturned pot. Charcoal was added via a hole in its side and lit, after which, the food to be baked was introduced, a vent at the top helped regulate temperature. A number of utensils evolved for the tannur– like the rolling pin, a special poker to pick up food and a metal scraper for cleaning the oven later. The mustawkad on the other hand, consisted of a fireplace built to accommodate multiple cooking pots at varying suitable heights. Utensils commonly found in the kitchen included clay pots, copper or stone, pans made from iron, skewers, knives, especially for cutting meat and vegetables, and mortars. As with any culture, the storage of food was important. Travellers, traders and armies could not always take livestock with them, and relied on preserved provisions. Excess food was not to be wasted. Grains stored in silos were protected from various pests. Fruits and vegetables were kept in airtight containers, sometimes buried underground, and melons from Khwarzam were packed in ice and kept in lead containers while being transported. Meat was preserved by treating it with salt and vinegar, but was preferred fresh.

Baghdad saw great marriages of cooking styles, and culinary art reached its pinnacle during the reign of Harun al-Rashid (786 AD – 809 AD) and his son Al-Ma'mun (813 AD – 833 AD), a period in history vivid in the pages of the Arabian Nights and such. With Makkah as the religious centre and Baghdad as its capital, the golden age of Islam was a time of intellectual and cultural awakening and for culinary activities. Culinary literature attained the status of an art in the areas of both pleasure and health.

The Kitab al-Tabikh, written by Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq, is the oldest surviving book of the time, and has detailed accounts of

recipes and anecdotes on cooking contests organised by the caliph.

The taste for special food and sweet things appeared during this period. Before that, spices had been only aromatic, and were used in tiny quantities, but in great number and varieties of combinations. Baghdadi cuisine was rich with many herbs and complex stews. Some had Persian names, such as Sikbaaj (flavoured with vinegar) and Naarbaaj (flavoured with pomegranate juice). The dishes with Arabic names, presumably developed in Baghdad, were often named after the main ingredient; for example, Adastyyah (lentils with meat) and Shaljamiyyah (lentils with turnips), whereas some were named for aristocrats.

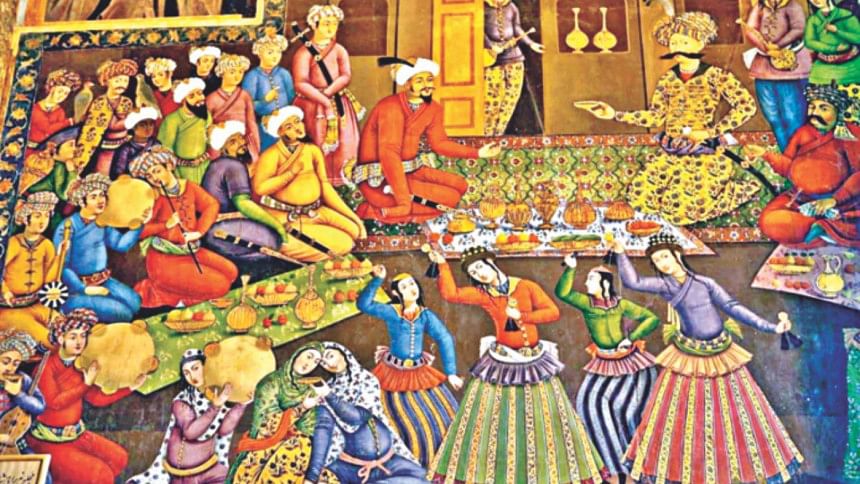

The royal banquets of the caliphs of Baghdad are legendary for their opulence. They merged the local peasant dishes and Bedouin foods of Syria. Lavish dishes were invented, poems praising food were recited and diners ate to the sound of music and singing.

The cuisine of the caliphs was transformed; new culinary techniques were acquired from the conquered people, and via trade routes beyond the empire. There came olive oil from Syria, dates from Iraq, coffee from Arabia, chefs came from Egypt, spices from India, Africa and China, but the strongest influence was of Persia.

PERSIAN CULINARY INFLUENCE

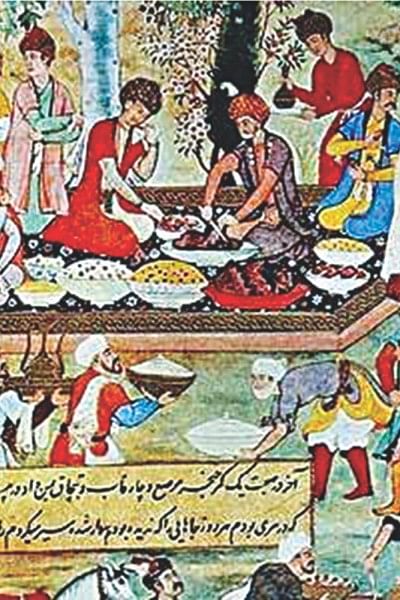

Persians have looked at food through three different lenses for centuries: as medicinal, philosophical, and cultural. Physicians and philosophers considered food and beverages the main factors in reviving the human body. Consuming food was seen as a way of weakening or strengthening human character. Culturally, food was considered to be an art, providing enjoyment to both body and mind. All of these were strengthened by the advent of Islam. The 7th century Arab conquest of Persia, was followed by invasions from Seljuk Turks and the Mongols. In Persia, Arabs found a sophisticated court with a rich cuisine, and eagerly adopted the local ways. Though no accurate record of classical Persian cooking is available, it is clear that the ancient Persians cherished food. For instance, Emperor Darius paid special attention to agriculture, and elaborate banquets were held in Persepolis. Walnuts, pistachios, pomegranates, cucumbers, broad beans and peas (known in China as the "Iranian bean"), basil, coriander, and sesames were introduced by Parthian and Sassanian traders.

Contemporary Persian cooking wears its heritage on its sleeve. Arabs gave Iran the art of making bread, which is still baked in traditional tandoors. However, rice has the place of honour, sometimes containing almonds, pistachios, glazed carrots or orange peels, and raisins, other times finished with vegetables and spices, and occasionally, with meat. It is often perfected and finished by the use of specially prepared saffron from Iran, and cooked slowly after boiling to have a hard crust at the bottom (tah dig). Rice dishes are considered special by Persians, partly because rice has been rare, grown only in the northern Caspian provinces. Persia's delicious aromatic rice has won many admirers. Jewelled rice (morasa polow) was described as "the King of Persian dishes" by James Morier, the shrewd English diplomat who knew Qajar Persia well, and wrote Haji Baba of Isfahan, the best comic novel on Iran.

Every meal is accompanied by refreshing drinks called sherbets made from diluted fruit and herb syrups. It is not known when exactly the sherbet came into being, but the earliest records date from 200 BC to the Shiraz school of cooking in Persia. The first sherbet is said to have been of almonds topped with lukewarm water. This mixture was strained and chilled before serving in porous earthen containers, which kept it cool. Today, all over the Middle East and Indian subcontinent, the popular sherbets are loved for their cooling, energy giving, and healing properties. Fruits, flowers, roots and vegetables can be used to make them. A samovar (traditional tea jar) is an essential part of every household as tea ranks with abdugh (buttermilk) as Persia's principal beverage, served in small slender glasses with lumps of sugar.

Lamb and chicken are marinated and grilled as kebabs, or mixed into stews called khoreshes with fruit and sour ingredients such as lime juice. Cinnamon, cardamom, and other spices are used in great abundance, along with a multitude of fresh herbs. They blend opposing flavours, such as sour grape juice with fresh herbs. They blend opposing flavours, such as sour grape juice with the sweet fresh herbs, which make Persian cooking quite exquisite.

Ice cream has been known for centuries to Persians, through a remarkable system that stored mountain ice underground through the hot months to provide cool drinks. Ice was not even a luxury.

MUGHAL CULINARY INFLUENCE

In 1526, Babur established the Mughals in India, who ruled for 300 years. The dynasty's legacy of food placed rich sauces and pilafs, nuts and dried fruit as the foundation of the Mughal cuisine of northern India. They brought with them the exotic heritage of Persian and Turkish cuisine, and influenced native cuisine with nuts, raisins, cream and butter. They added to the melting pot paththar kabab, haleem, aash, various kinds of polaos and much more.

The emperors' patronage took culinary art to the utmost heights. With their fall, the cooks found refuge with other courts across the sub-continent, accounting, to some extent, for the similarity of food across Pakistan, Bangladesh and India even today.

Photo: Collected

Comments