Fisherwomen left in the shadows by gender bias

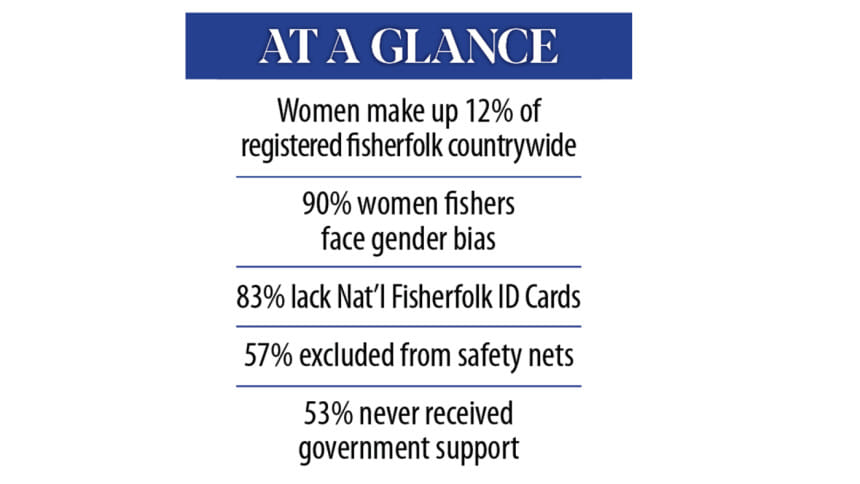

Despite playing a crucial role in sustaining Bangladesh's fishing communities, nine out of ten women fishers face regular gendered bias and remain largely invisible due to deep-rooted social, structural, and policy barriers, according to a recent study.

Their vital work, ranging from fishing in rivers and canals to net mending and fish drying, is often dismissed as "less important" compared to men's sea fishing. Frequently labelled as mere "assistants" rather than full-fledged fishers, women are denied the recognition and respect they deserve, the study added.

One of the most pressing hurdles is the difficulty in obtaining National Fisherfolk ID Cards.

An overwhelming 83 percent of women surveyed have yet to receive these essential IDs, effectively cutting them off from government aid programmes such as ration distributions, which disproportionately favour male cardholders.

In the study area, only 1,234 out of 6,695 registered fisherfolk are women, underscoring the gender gap in registration.

Subah Samara, assistant professor of public administration at Jagannath University, shared the findings yesterday at a policy discussion seminar titled "Empowering Women Fisherfolk Communities in Bangladesh", organised by Badabon Sangho at the International Mother Language Institute in the capital's Shegun Bagicha.

She highlighted that the lack of fisherfolk ID cards excludes many women from accessing low-interest loans through cooperatives. Instead, most are forced to rely on informal lenders charging exorbitant interest rates of 20 to 30 percent, trapping them in cycles of debt.

The study also revealed that women remain institutionally absent from governance and advocacy platforms, further deepening their invisibility.

Without proper registration, they are excluded from social safety nets, cooperative membership, and leases on state waterbodies, increasing their economic vulnerability.

Additionally, the research highlighted severe health challenges faced by women due to prolonged exposure to saline water -- issues worsened by climate change.

Access to clean water, hygiene products, and healthcare is limited, with local clinics often dismissing women's symptoms.

Specialised gynaecological services are largely unavailable, and the costs of treatment and transport are often prohibitive, which led to serious social consequences, including increased domestic conflicts, separations, emotional abuse, and early school dropouts, which in turn contribute to early marriages.

Additionally, 57 percent of fisherwomen remain excluded from social safety net programmes, while key policies such as the Jalmahal Policy and Fisherfolk Guideline largely overlook their gender-specific vulnerabilities.

Although 63 percent have completed registration, most have yet to receive their ID cards, blocking access to vital aid.

Off-season rice aid disproportionately favours male cardholders, and many women are forced to pay fees of Tk 3,000 to Tk 3,500 to obtain VGD cards.

Furthermore, 53 percent report never having received any government or administrative support, exposing significant unfulfilled promises and misaligned interventions.

Samara recommended strengthening the economic resilience of fisherwomen by forming cooperatives with access to revolving funds, providing market-relevant skills training, and ensuring universal issuance of fisherfolk ID cards.

She urged improvements in social protection through a simplified and transparent ID registration process, the creation of gender-specific safety nets, and expanded access to affordable credit to reduce dependence on exploitative lenders.

She advocated for local health camps, support for rainwater harvesting, and the removal of barriers to healthcare access, while emphasising the need to embed women's representation and priorities into fisheries, climate, and governance policies to achieve a gender-responsive transformation.

At the seminar, widow Farida Begum from Chila union in Bagerhat's Mongla, who has been fishing for 40 years, showing her hands, said, "Look at our hands -- whatever work men do, we do the same. We catch fish, steer boats, and our hands are marked with stains and scars. If male fishers get support, why shouldn't we?"

"We operate boats, get soaked in saltwater, and face tigers in the forest and alligators in the waterbodies to feed our children. Yet, the government provides us with neither food nor water tanks."

"If our names aren't on government records, I urge the government to remove women fishers like me from this earth altogether," said Farida.

Human rights activist Zakia Shishir stressed that discrimination stems from ingrained mindsets rather than policies alone.

"When we say 'fisherman' or 'jele', how many of us picture a woman? The real bias lies within our mindsets, not just in policies," she said.

She criticised policy-making detached from lived realities, calling for local contexts to be factored in and for women's voices to be formally recognised so they can claim their rights effectively.

Zakia criticised how policies are often made by officials detached from the realities of fisherfolk, rarely involving the actual beneficiaries.

She stressed the importance of considering local geographical differences for effective policy implementation.

Calling for formal recognition of women's work, she pointed out that women face compounded oppression from both social norms and patriarchy.

Badabon Sangho's Executive Director Lipi Rahman echoed the need for formal recognition, stating that many remain unaware of women fisherfolk's contributions, leading to neglect of their rights.

Department of Fisheries Deputy Director Firoz Ahmed acknowledged that after the district-level ID card project ended, the department has struggled to maintain ID card issuance.

While a recent project provided some cards through a vendor, many registered fishers remain without them, he said.

Shahajadi Begum, project coordinator at Oxfam, suggested expanding the scope of definition and registration coverage to explicitly include more fisherwomen.

She also emphasised the need to provide women-friendly alternative livelihood options using local resources, especially for those involved in catching fish fry, as many of these women lack skills for other types of work.

Speaking as chief guest, Dr Md Abdur Rouf, director general of DoF, assured that the definition of fishers will be revised to explicitly include women, as the 2016-17 registration guidelines currently omit specific mention of female fishers.

Illegal fishers are also being removed from the registration list, while genuine fishers are newly included.

Women fishers make up of 12 percent of the registered fisherfolk across the country, he said, adding that in the past six months, 37,910 fishers have been newly registered, and 23,644 registrations have been cancelled.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments