The war waged by a heroic woman . . .

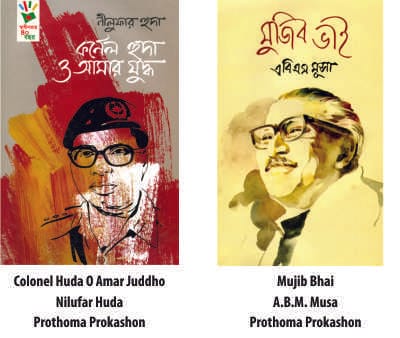

Be forewarned. This is one work which will sadden anyone who reads it, for it comes from a woman who has suffered intensely, lived and loved completely and remembered poignantly. Nilufar Huda's life could and might have been different had politics and war not come in her way. Colonel Huda O Amar Juddho is the war she has waged for decades. To comprehend the nature of her war as an individual, you need to go back to the two wars which left her life changed for ever, to a point where the happiness she looked forward to quickly and dramatically gave way to tragedy.

Nilufar Huda, born in village Salar in Murshidabad and raised and educated in Calcutta, travelled to East Pakistan in 1965 to be part of a relative's wedding. She was unable to return to her country, for by then war between India and Pakistan had broken out. When she did return to Calcutta six years later, in 1971, she had a son and a daughter with her and she had a husband who had gone off to war to liberate East Pakistan as Bangladesh from the rest of Pakistan. The years between 1965 and 1971 were, in short, a time when she met Khondokar Nazmul Huda, a young Bengali officer in the Pakistan army, fell in love with him and eventually married him. On his various postings in East Pakistan and then in West Pakistan, Huda made sure his family was with him. Life for the couple appeared promising and laced with prospects of Huda's rise in the Pakistan military structure.

Until the Agartala case came along. Huda, along with thirty four other Bengalis, was charged with conspiracy to have East Pakistan secede from the rest of the country and taken into custody. Unknown to his wife, then at their residence in Ugoki in West Pakistan, the young officer was flown to Dhaka and subjected to inhuman torture by the army. Not until the day the trial of the accused, among whom Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was at the top of the list, began in June 1968 that Nilufar saw Huda for the first time since he had been spirited away from his home in West Pakistan. Nilufar Huda's impression of the future Bangabandhu is of the glowing sort. Alone among the accused, Mujib remained confident, with no trace of fear in him. Placing his hand on Nilufar's head in avuncular affection, he reassured her that all those on trial would emerge free and that no harm would come to them.

Amar Juddho ought to be read in two layers of understanding. The first is certainly the writer's assessment of her husband as lover, husband, father and freedom fighter. The second, rather importantly, is the re-enactment of the conditions we have all lived through from the 1960s and right up to the tragedy of November 1975. Huda's dedication to Bangladesh was unalloyed, even when after the withdrawal of the Agartala case in February 1969 and his discharge from the army he was compelled to make ends meet through engaging in small time trade. Nilufar presents reality as it was. The couple went through terrible times paying their house rent and moving house from time to time. She lets readers know that among the ordeals she and Huda faced, even as Pakistan prepared for its first general election in 1970, was the sheer difficulty in buying milk for their baby.

And then came the War of Liberation, into which Huda plunged with alacrity. His professionalism was all. Trusting the welfare of the family to his wife, he went off to organise the resistance against the Pakistanis. Of course he did link up with his wife and their two children in the course of the war, once accompanying them all the way to Calcutta; but his focus on the war was unwavering. When Nilufar sent him blankets and other items for him to be comfortable in on the battlefield, he returned them to her, informing her in no unclear terms that he preferred to lead a life just like any other soldier. And he did precisely that, right till the day Pakistan surrendered in Bangladesh.

Those were stirring times in the weeks and months after liberation. Huda played a leading role in organizing the fledgling Bangladesh army. The military academy in Comilla remains a monument to his career. And yet it was this very army which took Huda's life, together with the lives of General Khaled Musharraf and Major ATM Haider, on 7 November 1975 in what was eerily a counter-revolution. Nilufar Huda's observation of the events that led to the death of the three war heroes at Sher-e-Banglanagar raises a whole plethora of questions yet once again about the men behind the criminality. Col. Nawazish Ahmed, later hanged over the Zia murder, informed a freed General Zia of the three officers' arrival at 10 Bengal. Col. Taher, who was in the room where Musharraf, Huda and Haider had been detained, went out at some point. Just as the three men were being served breakfast (they had earlier said they needed food) some other soldiers rushed into the room, forced them out at gunpoint and shot and bayoneted them to death. Another dark chapter was thus added to free Bangladesh's history. Bangabandhu and the four national leaders had already been dispatched.

Nilufar Huda writes with no rancour in her. She has fond memories of General Zia admiring her garden; she speaks of General MA Manzur, who came forward with offers of help after Huda's murder, with gratitude; she remembers General Nurul Islam Shishu with special fondness; and when Nawazish's wife asks for her forgiveness in the aftermath of her husband's conviction in the Zia murder case, she is not bitter at all.

Colonel Huda O Amar Juddho is a tale of love and war, of heroism and betrayal, of a young, beautiful woman's resolute struggle to reshape her life and those of her children in a country her husband caused to be born. You read this book. And you know what an epic could or should be. It is an epic tale here.

. . . A journalist remembers

a towering

politician

Bangabandhu possessed a remarkable sense of humour. That fact comes through yet once more, this time in A.B.M. Musa's reminiscences of the Father of the Nation. The veteran journalist, one of the few mediapersons to have interacted closely with the founder of Bangladesh, beginning with the 1960s and continuing well into the mid-1970s, recalls in Mujib Bhai the moment when a mischievous Sheikh Mujibur Rahman decided to give responsibility for the health and family planning ministry to the very lean Zahur Ahmed Chowdhury. He had his reasons. Chowdhury's appearance would emphasise the great need for healthcare in the newly independent country. At the same time, the family planning part of the portfolio would come in handy considering that Chowdhury had two wives and had between the two of them fathered fourteen children. When visiting Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi gave each of Bangabandhu's ministers a saree for their wives, Mujib quickly took away the saree she had given to a minister, in this case Monoranjan Dhar, who happened to be a bachelor. He explained to a surprised Indira: 'A bachelor has no need for a saree. So this saree can go to Zahur Ahmed Chowdhury since he has two wives and a single saree will simply not do.'

Musa, whose career in journalism has spanned decades and in the course of which he also served as a member of parliament (he was elected in 1973), brings into this work a set of articles which have been published in newspapers over the years. In essence, they are a glimpse into the personality of a politician who by gradual yet sharp degrees rose to being the most significant political figure in the history of Bangladesh. Musa carefully stays away from a discussion of Bangabandhu's politics, which is just as well, for the diverse chapters in the work bring out the qualities which in his lifetime and even after his death have marked Bangabandhu out as a leader with the common touch. One might well come up with the question of why Musa addresses Mujib as Mujib Bhai rather than as Bangabandhu. He as also his contemporary Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury, whose preface to the book only adds to the richness of the Mujib personality, make it obvious that their association with the founding father of Bangladesh goes back to a time when Mujib was a struggling politician. He was a brother, bhai, to everyone. To many others, especially in the rural interior of the country, he was --- and still is --- Sheikh Shaheb. It is immaterial how many Sheikhs there are in the country. For Bengalis, Sheikh is a reference to just one man --- Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Of course, Mujib became Bangabandhu soon after his release from the Agartala conspiracy case, but those who had known him since earlier times never quite forgot that he was their Mujib Bhai. And Bangabandhu, to the end of his days, felt buoyed when he was addressed as Mujib Bhai by those who met him.

The writer's admiration for Begum Fazilatunnessa Mujib is without ambiguity. Throughout her adult life, as her husband went in and out of jail because of his politics, Begum Mujib kept the home fire burning in the darkest of hours. Not many women, apart from Kasturba Gandhi, Kamala Nehru and Winnie Mandela, can equal the forbearance and toughness Bangabandhu's wife demonstrated in all the years when successive Pakistani governments made life hugely difficult, not to say miserable, for her husband. Firmness of principle and strength of character, Musa says as much, underlined her personality. When rumours abounded of Mujib's imminent release on parole to enable him to attend the round table conference called by President Ayub Khan in Rawalpindi, Begum Mujib had a firm warning sent to her incarcerated husband: 'You may attend the round table conference on parole, but then do not ever think of coming back to 32 Dhanmondi.' Fazilatunnessa was the quintessential Bengali housewife, never failing to entertain visitors. Her offering of betel leaves to guests was a celebrated affair. Musa speaks of the times she would slice betel nuts into pieces in traditional fashion. Far from her mind was the thought that she was the spouse of the man who was not just prime minister but the Father of the Nation as well.

A.B.M. Musa exposes the lie behind the malicious reports of Sheikh Kamal's alleged involvement in a bank robbery. Describing Kamal as the brightest of Bangabandhu's three jewels (the others were Jamal and Russell), he makes it clear that Kamal had come to know about a planned bank robbery through two players of the newly established Abahani sports club. With his friends in tow, he rushed to Motijheel, where police superintendent Mahbub also turned up with his force. Two of the would-be robbers were injured in a shoot-out with the police. Musa's account only reinforces the argument that in those early days of liberation, many were the elements arrayed against Bangabandhu, always ready to badmouth his government.

Mujib Bhai reveals Bangladesh's founder in both his moments of joy and despair. With little to show for a well-defined administrative structure in place, Bangabandhu wondered why those seeking quick results from him did not understand that he was trying to run a country with people who had had no experience running even union councils. Candour underlined his personality. A largeness of heart was what endeared him even to his enemies. On his return from Pakistan in January 1972, Bangabandhu asked Musa to locate Badruddin, till liberation editor of the rabidly anti-Mujib Morning News newspaper. Musa discovered him in hiding in Dhaka's Lalmatia. Badruddin was surprised that Mujib had been asking after him. On meeting Bangabandhu, he expressed his wish to be allowed to travel to Pakistan. He was soon there, thanks to the man he had for years vilified in his columns. Years after Bangabandhu's assassination in 1975, Badruddin and Musa chanced to come across each other. Badruddin had a simple question for Musa: 'You people killed this angel of a man?'

Musa's account promises to be a significant addition to the literature on Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. He recalls Moulana Bhashani's tearful joy as he welcomed Bangabandhu to Santosh soon after the Father of the Nation returned home from imprisonment in Pakistan. Prophetically, standing before the television cameras and newspaper reporters, Bhashani warned, 'Mujibor is not yet out of danger.' The danger would come three years later.

With Musa, Gaffar Chowdhury and Faiz Ahmed, Mujib enjoyed a rapport that journalists in these times, as they deal with politicians around them, can only dream of. Bangabandhu called the trio 'apod bipod musibot' --- in rough translation, calamity, danger, difficulty.

Syed Badrul Ahsan is Executive Editor, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments