Economic life carved in history

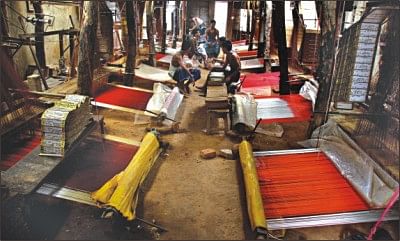

Handcrafted textile was a major trade item in the Mughal era.Photo: STAR

It was a special end to the celebrations to mark 400 years of Dhaka. Seminars and sessions focusing on different aspects of history, economy and culture were nearly fairytale-like -- just crafted with facts.

Experts and historians from Bangladesh and India reminded the audience that the economic life of Dhaka was fairly busy even before the city became the capital of Bengal Suba in 1608.

In his paper titled Economic Life of Dhaka (1608-1947), Dr M Mufakharul Islam, professor of history at Dhaka University, said developed indigenous industries and better transport through rivers of this region were the two major factors that promoted economic growth.

He wrote the paper jointly with Delwar Hassan for the three-day international seminar on 'History, Heritage and Urban Issues of capital Dhaka', organised by Asiatic Society of Bangladesh at Dhaka University last month.

“At that time, growth was mainly led by famous fine muslin makers and spice traders, who made international footprints by exporting goods through waterways, where Dhaka's rivers and canals played a vital role,” he said.

“According to Chinese and Greek travellers, Savar and Bikrampur, the adjacent areas of Dhaka, started flourishing as trade centres mainly from the 11th century during the end of the Pala dynasty and initial period of the Sena dynasty,” the history professor added.

Along with trade relations with China, Greece and Italy, the ancient city's economic life was dependent on agriculture and craftsmanship, supported by recent excavation at Wari-Bateswar.

However, Dhaka emerged as a thriving commercial and industrial centre after the Mughal rulers shifted the capital of Bengal from Rajmahal to Dhaka.

The political change brought significant transformation in the local economy, as the Mughals brought a huge number of artisans and royal court staff, who introduced a new economic way of life with multiple professions, he said.

“Then, as a manufacturing town, a centre of conjunction and a Saha Bandar, Dhaka attracted merchants and traders from different parts of India and overseas. It also created a great number of shroffs, bankers, podders and mahajans, who played a vital role in the city's economic and social life,” said Islam.

“Handcrafted textiles, milk products, jewellery, pottery, paper making and boat building were the principal trade items during the Mughal and Nawabi era,” he said. “Dhaka's commercial excellence and economic prosperity presented lucrative opportunities for traders from Armenia, France, Portugal, Greece and the United Kingdom.”

The influx of foreign traders influenced gradual economic growth and socioeconomic aspects of the city considerably, as they had set up their Kuthir, agency houses and factories in and around Dhaka, Islam added.

However, the transition from Mughal to the East India Company rule in Bengal led to many institutional changes, especially to manufacturing and economic systems.

Modern banking evolved in Bengal in the British period with the establishment of the Hindustan Bank in Calcutta (now Kolkata) in 1700.

But the Bengal Bank, established in 1784, is considered to be the first British-patronised modern bank in India to start trading in credit and money, which had loan offices in major towns in the then East Bengal.

When the city lost its political and administrative significance in the early eighteenth century, the indigenous industries declined due to the unfavourable British policy towards the textiles industry in the subcontinent.

With other crafts remaining more or less unchanged, muslin weavers were converted into farmers, goldsmiths or got involved with trading activities at the time.

In the eighteenth century, a huge trading and manufacturing class developed in Dhaka, including foreign mercantile companies, factory weavers, banians, gomostas, brokers, pikers, mohajans, podders, craftsmen, washer men, palanquin-bearers, painters, weavers, craftsmen, gold and silver smiths and shopkeepers.

“All these imply at the existence of a high consumer class as well as a working class in Dhaka,” said Islam.

“A mint-house, where the official coins of a country are made, was set up to meet demand, and podders, sheth and bankers flowed in from different parts of Bengal.”

Among the locals, Sahas and Basaks, two entrepreneur classes, led Dhaka's business considerably, the paper said.

In addition, the rise of landed market, large pieces of land generally belonging to a family for several generations, was another significant aspect to the city's economy. The participation of company servants in Dhaka's business was an added factor to this effect, he explained.

Trade in European goods became a new source of wealth for the city. Although the textiles industry was declining by that time, there was gradual growth in the leather and jute industries, and this commercial revival gave a new boost to the economic life of Dhaka.

Dhaka recaptured its royal status when it was again made the capital of Eastern Bengal and Assam in 1905, though the cancellation of the Bengal partition in 1911 was a setback to economic growth of the city, said Mufakharul Islam of Dhaka University.

At that time, revival of jute markets and business marts in and around Dhaka and emergence of Narayanganj as a substantial port city configured a new pattern in economic order, according to the paper.

However, in 1947, Dhaka again experienced a new socioeconomic life at the arrival of migrants following the partition of India, when the city became the capital of East Pakistan.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments