The forgotten harbinger of the language movement

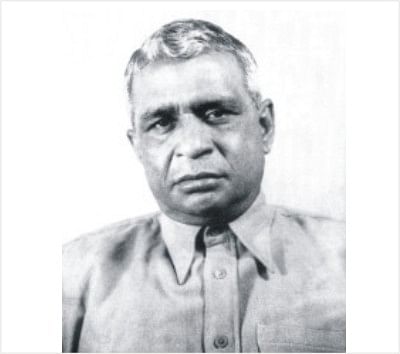

Dhirendranath Datta.Photo: STAR

THE Bengali language movement did not begin all of a sudden on February 21, 1952. Rather, it took place in the then East Bengal in several distinct phases in the early years of Pakistan. The formative phase took place in two stages. The first stage started immediately before and after the emergence of Pakistan on August 14, 1947, and the second stage took place in the early months of 1948, but they were not mass uprisings by any standard.

Yet, the restive student community and the intelligentsia were able to garner more mass support throughout the then East Bengal for making Bengali one of the state languages of Pakistan. Those initial reactions against the unilateral imposition of Urdu as the only state language prepared the progressive forces of the eastern province of the then Pakistan for launching an effective Bengali language movement in early 1952.

The final phase of the Bengali language movement began in early 1952 after Khwaja Nazimuddin, the then prime minister and a lifelong anti-Bengali collaborator, declared in a public meeting at Paltan Maidan on January 26, 1952, that Urdu would be the only state language of Pakistan. There is no doubt that his provocative speech can be singled out as the immediate cause of the 1952 phase of the language movement.

Any credible assessment of the organised efforts toward establishing Bengali as a state language would add credence to the fact that the language protests and demonstrations in the early years of Pakistan had a clear bearing on the extent and magnitude of the historic movement in February, 1952.

The language movement was not the making of any single individual or any particular political party. Many student leaders spearheaded it in all of its phases. Although the marginal roles of some of the participants have often been magnified through systematic distortions, exaggerations, manipulations and invented memories, there had been ample opportunity in those turbulent early years of Pakistan for many patriots for participating in that defining struggle.

Indeed, there were many actors who were involved in the different phases of the language movement. Of those genuine language activists, Dhirendranath Datta's (1886-1971) name can be singled out as the illustrious forerunner of the formative phase of the Bengali language movement. Indeed, he was the harbinger of the movement in the early years of Pakistan. He made history on February 25, 1948 by demanding that Bengali be recognised as one of the state languages of Pakistan, even though his amendment was a proposal for adopting Bengali as one the official languages of the central legislature of Pakistan.

The unresolved language controversy continued to surface during the early months of independent Pakistan. The rejection of Bengali and the unilateral imposition of Urdu as the "only" state language spawned a feeling of distrust and discontent among the student community and the progressive forces of the then East Bengal. In fact, the language issue exposed the hidden anti-Bengali agenda of the Punjabi-Mohajir dominated central government of the new nation of Pakistan.

There is a plethora of evidence to suggest that the patriotic forces of East Bengal had started mobilising and enlisting public support for making Bengali one of the state languages of Pakistan immediately before and after August 14, 1947. There is no doubt that those initial efforts against the ulterior motives and anti-Bengali policies of the Pakistani ruling elite were not mass protests. They were confined within the pages of newspapers, pamphlets, articles or statements.

The language movement started taking a more concrete and volatile shape throughout the then East Bengal in the early months of 1948. There were many language activists who were in the vanguard of the formative phase in 1948. Yet, Dhirendranath Datta's role was undoubtedly seminal in the process of jumpstarting our resistance against the anti-Bengali forces. His courageous speech in the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan (CAP) on February 25, 1948, in favour of making Bengali one of the state languages ignited the 1948 phase.

Among all the genuine leaders of the formative phase, Dhirendranath Datta's role was pivotal in building up an organised resistance against the anti-Bengali forces who were deliberately engaged in repudiating the Bengali culture and language. Instead of supporting or endorsing his fair amendment for adopting Bengali as one of the official languages of the CAP, his proposal was quickly labelled by the Punjabi-Muhajir dominated government as an "anti-state" and "anti-Muslim" ploy for destroying the "Islamic" character of the new nation of Pakistan.

His patriotism and the loyalty of those few legislators who lent support to the amendment were openly questioned on the CAP floor. Finally, the Muslim League dominated CAP quickly rejected Dhirendranath Datta's historic amendment.

His amendment was consciously designed to accomplish much broader societal goals for the people of the then East Bengal. He was fully aware that his demand might be deliberately misconstrued by the ruling coterie of Pakistan. Since he was from the minority community, he also knew that his "patriotism" would be under the scrutiny of Pakistani ruling elite.

Dhirendranath Datta's demand also exposed the hidden anti-Bengali design of the non-Bengali ruling coterie. Despite the fact that the communally motivated ruling coterie had started disseminating blatant falsehoods and slanderous distortions about the legislators from the minority community, he fearlessly continued to demand, both at the CAP and East Bengal Legislative Assembly (EBLA), the adoption of Bengali as one of the state languages.

Although the ferocity of the formative phase of the Bengali language movement had waned during the years between the middle of 1948 and early January 1952, the activists and the progressive political forces,including Dhirendranath Datta, remained vigilant against the ulterior design of the anti-Bengali Pakistani political elite of the central government and the pro-Urdu provincial government of the then East Bengal.

Dhirendranath Datta was not murdered by the retreating Pakistani occupation forces. His murder was planned. He was not a random casualty of cross fire. Nor was he a victim of mistaken identity. The Gestapo style abduction of Dhirendranath Datta (along with his youngest son Dilip Datta) by the brute Pakistani soldiers from his Comilla residence on March 28, 1971, and the cruel methods through which he was tortured to death, lend credence to the fact that the collusive Pakistani ruling elite did not forget his pivotal role in the making of the formative phase of the Bengali language movement.

It is obvious that the genocidal Pakistan army was fully aware that Dhirendranath Datta was not only an ardent defender of Bengali language but was also vocal against various anti-Bengali policies and ploys of the central government. His brutal elimination at the beginning of Bangladesh's liberation war was also designed to cripple the nation intellectually. His murder made it obvious that the Pakistani military junta wanted to deprive the Bangladesh government in exile of his participation during the liberation war.

Instead of just thinking morally and ethically, Dhirendranath Datta had acted morally and ethically by speaking in favour of saving the mother tongue of the majority people of the then Pakistan. His moral stand and action can be characterised as Aristotelian "ethics of virtue" as he did believe that the best way of developing "skills of virtue" was by practice. As said by Aristotle a long time ago: "The virtues we get first by exercising them. For the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them. We become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts."

Dhirendranath Datta acted courageously, and he was willing to take any kind of risk in his valiant fight for rescuing his mother tongue from the cultural aggression of the repressive colonial ruling elite of Pakistan. Whatever he did to defend his mother tongue at a critical juncture of our history, he did out of his deep conviction.

The historic Bengali language movement in all of its phases was one of the most defining moments of Bangladesh's history, and the foundation of the language-based nationalism that led to the emergence of Bangladesh was clearly laid down during the formative phase of the Bengali language movement.

The sacrifices of the language activists and the language martyrs of that glorious movement did not go in vain. The lasting legacies of the Bengali language movement and the language martyrs have transcended the test of time. Indeed, Shaheed Dhirendranath Datta's courage and his sacrifices as a dauntless defender of the Bengali language and culture will be remembered beyond the boundaries of time.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments