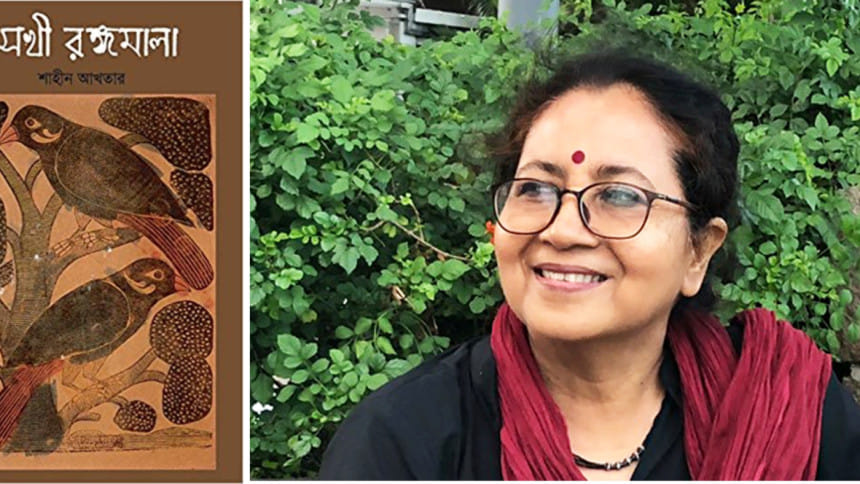

Shaheen Akhtar Representing Multi-faceted Identities

Shaheen Akhtar is a notable Bangladeshi author, who won the Prothom Alo Best Book Award in 2004 for her novel Talaash, (translated into English as The Search and published by Zubaan, Delhi, in 2011). Bengal Lights Books published the translation of another novel Shokhi Rongomala (Beloved Rongomala) in 2018. Her short stories have been published in Words without Border and other prestigious literary magazines. Akhtar was presented with the Sera Bangali 2014 Award for literature by India's leading Bengali news channel, ABP Ananda. She has also received the Akhteruzzaman Elias Kothashahitya Puroshkar 2015 and the IFIC Bank Puroshkar for her novel Moyur Shinghashon. Akhtar's works have been translated into English, German, and Korean. In 2015, Akhtar received the highest national award for literature in Bangladesh, the Bangla Academy Literary Award, for her contributions to Bangla literature, and in 2019, she received the Gemcon Literary Award.

Arifa Rahman (AR): You have recently won the GEMCON Literary Award for your novel Oshukhi Din. Congratulations! Can you tell us about that?

Shaheen Akhtar (SA): Thank you.

Oshukhi Din is a novel set in the forties of the last century. It was the decade of a world war, famine, riots, and the Partition. The colonizers were leaving and maps were being redrawn to determine our futures.

Partition in Bangladesh is a complicated affair for various reasons. Perhaps that is why there has been a tendency to avoid the topic in our history or literature books. One major reason was that soon after the birth of Pakistan, East Bengal was forced to take a stand against the state of Pakistan. Then followed the Language Movement in '52 to the achievement of Liberation in '71. Our history and literature became involved in trying to capture this tumultuous time.

Writers perhaps had another thought in mind – since the refugee crisis resulting from the Partition was not as severe here as it was in West Bengal, what could they say about the issue?

In truth, there is no simple story about the Partition here, whether about the sorrows of being a refugee or the joys of attaining a new country. I think I wanted to convey this in Oshukhi Din, mixing the past and the present from the viewpoints of two characters from two generations, from two different worlds. I wanted to construct a non-existent world like piecing together a puzzle. I don't think there is any opportunity to tell the story here in a straightforward, beginning to end manner as in the classics. The story of the forties came to us in impossible tatters.

The history of the Partition and our current situation is different from Pakistan or India. I tried to write the book from our geographical and cultural perspective. This area is still new but I think the possibilities are many and it is necessary to work on it. I especially think that, at the very least, we should expand our study of the history of the time much further back from '71 and '52.

AR: What inspired Oshukhi Din?

SA: I believe the seed of inspiration for this novel is ancient – and it was planted in Chittaranjan Park in Delhi. During a documentary film course, my training film was about a refugee. This was around '89 or '90. It was the touching memories of a retired widower by the Padma. He was living in a small apartment in Chittaranjan Park. It may have been around this time or later that I heard many stories of the Partition in Delhi and Kolkata. I have even seen these stories change after the Babri Masjid incident. I didn't think at that time that the Partition stories belonged only to them. I was becoming a part of them but I was reluctant to be held accountable. I thought of the stories I had heard of some invisible neighbor in my childhood. They were there, and then they were gone. The devastating storm of the Liberation War of '71 caused those stories to disappear.

I'm not sure if this experience was really the inspiration behind Oshukhi Din but it must have become honed inside my head as I thought about it repeatedly. Then, many years later, when I read Jaya Chatterjee's "Bangla Bhaag," my glasses almost fell off my face. But nothing is ever the last word.

AR: So, what kinds of writing did you read while growing up?

SA: I was a reader of literature much before I began to write. There was a steady influx of Russian literature published by Pragati Prakashani in our home during my childhood. My two older brothers would bring them, so I began reading the Russian classics when I was still quite young. In fact, at that time, I read whatever I could lay my hands on: Romena Afaz, Niharranjan, Bomkesh. But, I think, I have been more influenced by the classics.

AR: And when you write, do you choose your subject matter or does your subject matter choose you?

SA: I initially make the choice. But then, sometimes, some ideas rush in, almost like unwanted guests.

Let me give you an example. I was still in the process of writing my novel Oshukhi Din when the Rohingya began to cross over the Naf River during the monsoon. The news of their coming did not sound real. To me, it sounded like the story of the Exodus in the Bible. The stories of Bihari Rahmatullah or Pahari Dibakar are much like Musa's in "Oloukik Chchori" – stories of refugeehood in their past and present. In today's world, anyone could become a part of this kind of exodus.

The murder of our hostel superintendent was tragic. She was someone we imitated in our adolescent years and her death was not just tragic for us, it felt like the demise of our own adolescent selves.

My pen ran dry with the news of Abrar Fahad's brutal murder – filled only with numbness and helplessness like at the death of a dear one.

AR: I see. However, you write mainly about women; that is, your main characters are usually women – why? Also, a lot of your protagonists belong to marginalized social groups, not someone from the mainstream. Have you seen such women or talked to them or met them?

SA: After finishing my Masters degree, I was introduced to film-making and I made documentary films for a living. I was a working, single woman (this was towards the end of the eighties) and finding a place to live was difficult. This situation allowed me to gain some experiences of being a woman in this city. This became the initial fodder for my literary career. I wrote about things I knew or was going through. Creative writing offered a respite for me and I moved from documentaries to fiction. So, my early writings are mostly my experiences, only somewhat fictionalized, since I wasn't writing autobiographies or memoirs, but short stories and novels. I think the first time I stepped out into the unknown was with Talaash. It was about the rape survivors of the '71 Liberation War.

Regarding women characters, I think the inspiration for my writing inevitably brought them into my stories and they continue to come in even today. They are not anyone unfamiliar to me. In some way or the other, I know them. Sometimes, an isolated incident acts as a trigger and then the rest is imagination. Or perhaps, they turn out the way they are in the course of the writing. I believe the stories have both marginalized and mainstream characters – I think what's important is what facets of their character eventually emerge.

AR: You work at a Human Rights organization. Has this influenced your writing at all?

SA: Actually, my life isn't focused on or around my work. I have been working part-time for many years. I have, of course, witnessed many different incidents at the office which provides legal aid and perhaps, unknown to me, bits and pieces have crept into my stories. The only exception is Jesmin from "Ma." My office was a direct source for the theme of this story.

AR: Tell me about your birth, childhood, education, job, and anything else that is interesting about you or identifies you. Does anyone else in your family write? Or wrote? – your Mother/Khala/Fupu/Sister – who may have inspired or motivated you?

SA: I grew up in the village but there was a literary environment in my home. My mother was a bookworm. My two older brothers and my Mama used to write. Seeing them, I was inspired to start writing or pretending to write when I was still in school – hiding what I wrote, in great trepidation. That's what my Mejho Khala, Badrunnessa, did her whole life. Thirty years after her death, her son discovered countless manuscripts of stories and novels in a trunk. Obviously, Khala had not been writing for fame, or we might have seen her works in at least the pages of the illustrated Begum magazine. My cousin typed up the manuscripts himself and had them published. I worked with him on editing these manuscripts which are actually testaments of a bygone era, the sixties and the early seventies.

As for me, I was a precocious child and read all kinds of novels or heard their stories. I used to make up stories and say they were written by some famous writer to make people listen. We had a big family. The elders never paid attention to what we were reading or whether we were reading books too mature for us. Not being under the elders' radar must have worked because I could expand the depths of my imagination.

I started writing in school. I scribbled on the ruled pages of copies, like talking to myself. I never thought of publishing at that time. My first story was published when I was in college, in a Cumilla magazine called Aamod. I don't remember what it was called.

AR: Quite a few of your works have been translated (several of your short stories by me as well). I'd like to know, however, why, in your opinion, is it necessary for your writings to be translated?

SA: Not just my writing, but I think literature should always be translated. It has been happening from our distant past. My novel Talaash, for example, was translated into English in 2011 by Delhi's Zubaan. When it was later translated into Korean, it created quite a stir. The book received such acclaim, such love from the Korean readers that I found it unbelievable.

AR: How do you see yourself within the literary tradition of Bengal and Bangladesh?

SA: The scope of Bangla literature is huge. I have to look at myself through a microscope and I can only speak for my process and my writer's identity.

I write short stories and novels. And I take my time. I experiment with the language and the form. And I pursue such inaccessible topics that it's like scaling mountains. Or like throwing myself into a hole and testing myself. I will have to rescue myself, even if it takes three or four years. Any writing is challenging for me, whether it's a short story, non-fiction or a novel. I always suffer from doubt about whether I will be able to write or even finish. And yet, I like my vulnerable writer self. I love being involved in traversing the long difficult path through the writing of a novel. Under pretext of writing, I travel, read, live in a half-trance and I create a half-literary world with all these. I wish I could curl up inside a shell like a snail while I am writing. I have no idea if I will ever graduate to the level where I would be completely immersed or focused on a point during writing.

AR: You have also won the Bangla Academy Literary Award. What advice would you have for the younger generation of writers?

SA: Well, I don't think I'm the type of writer who qualifies to give advice. I think my writing portrays the time I grew up in and the time in which I live. Sometimes I view this in the mirror of the past. So, though my journey is towards the past, my fingertips remain in the present. I mean that I see the past through the present. Fiction is not history. Even if it takes refuge in history, it is still imaginary. The shadow of the present merges with the imagination of the past. It reflects the writer's experiences of memories, stories heard, and read.

I think novelists can work with subjects from their own time that reflect their own identity and through which they can uphold their culture. In these cases, it is important that they do not rely on others' formulae, but leave a stamp of their own. For instance, the Pakistani or Indian literature on the Partition would not be the same as ours. Our historical reality and experiences are completely different.

We still view the Moghuls through the eyes of the British colonizers. Or, we might say, through the eyes of the current communal ruling groups of India. The view should be ours. Frankly, it is necessary for the incomparable beauty, fragrance, and grace of classic Moghul culture to be represented in our literature. That will illuminate, in essence, our multi-faceted identity.

AR: Thank you so much for your insightful views, Shaheen apa.

SA: My pleasure.

Arifa Ghani Rahman is Associate Professor of the Department of English and Humanities at the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments