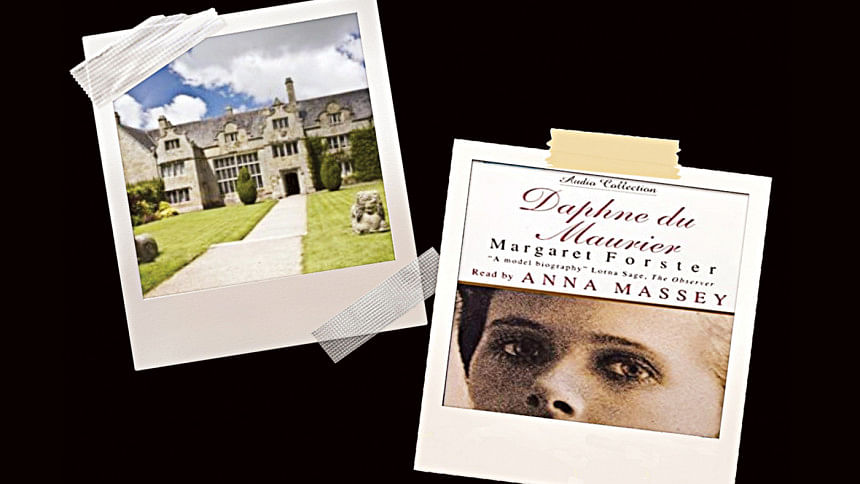

Long books to lose oneself in during lockdown: Margaret Forster’s Daphne du Maurier

ISBN: 9780385420686 Chatto & Windus, London, 1994

On offer is a remarkably candid biography of Daphne du Maurier (1907-1989), the powerful story-teller of the twentieth century; highlighted by her singly recognised classic novel, Rebecca (1938). At the time, Daphne herself had her doubts about the book's success and wrote to her publisher Gollancz: "I've tried to get an atmosphere of suspense...the ending is a bit brief and a bit grim...It was certainly too grim to be a winner." Forster declares: "Daphne had been wrong: she, and Gollancz, had their winner." Alfred Hitchcock directed both film adaptations of Jamaica Inn in 1939 and Rebecca in 1940. The Scapegoat was filmed in 1959 with Alec Guinness in the lead and Bette Davis in a supporting role. She had a long illustrious and prolific literary career resulting in 37 books; fiction, non-fiction, biographies and autobiographical writings, e.g. Growing Pains: The Shaping of a Writer (1977) and The Rebecca Notebook and Other Memories (1981). In 1969, she was bestowed the honour of Dame of the British Empire. Daphne du Maurier had great admiration for Harold Wilson. He was her "pin-up boy." Upon assuming the post of Prime Minister, she congratulated him and wrote to Mary Wilson. Memorably, Mary Willson replied: "that on the first day at 10 Downing Street she had felt like the second Mrs. de Winter in Rebecca." The epic masterpiece continues to resonate.

A Cornwall resident to the core, her long-rented home "Menabilly" was the inspiration for the house "Manderley" in her "Gothic romance" genre novel Rebecca. Decades of efforts to purchase Menabilly from the family owners, the Rashleigh never materialised. Rosalind Ashe in her delightfully imaginative book Literary Houses: Ten Famous Houses in Fiction (1982) elaborates: "The houses in these novels are more than mere stage sets: they are almost 'characters.' They linger in your mind long after the book is closed. They have become real." Manderley remains one formidable character in the history of literature. Forster writes: "'Menabilly' was always more than a house to Daphne du Maurier. Its chief attraction for her was its secrecy, not its size or beauty or history." At Menabilly, Daphne redefined her sense of belonging. This is where her creativity peaked; in a self-created imaginary world of her own choosing. The swashbuckling star of the Hollywood silent screen, Douglas Fairbanks (1883-1939) raised a vital question: "When someone is writing, where do they live: in the real world or in a self-created elsewhere? Not bound by walls." Menabilly, her retreat and refuge, provided Daphne du Maurier her required sanctuary and succour for multiple "mid-life crises" that impacted her throughout her life.

Meticulously researched with ample access to private letters, papers and interviews, Forster discovers hereto unknown layers of the dark-edged depths of her subject's personality. Open cooperation with immediate family members - particularly Daphne's two daughters, Tessa and Flavia and her son Kits; her extended family, close friends, her publishers Victor Gollancz Ltd, housekeeping staff and their respective descendants reveal insights into storms brewing under the popular writer's calm surface. Sensitively reading between the lines of information gleaned, Forster has successfully worked the state of inner conflict and intimate negotiations which Daphne tackled all her life - a complex inner labyrinth of sexual identity crisis. Her deft amalgam of a broad blend of sources makes for an immersive literary experience.

Her father, Gerald du Maurier a successful theatre producer in London, regarded Daphne as the son he never had. He wrote a poem to her:

....

My tender one -

Who seems to live in Kingdoms all her own

In realms of joy

Where heroes young and old

In climates hot and cold

Do deeds of daring and much fame

And she knows she could do the same

If only she'd been born a boy.

And sometimes in the silence of the night

I wake and think perhaps my darling's right

And that she should have been ,

And, if I 'd had my way

She would have been, a boy.

....

And sometimes in the turmoil of the day

I pause, and think my darling may

Be one of those who will

For good or ill

Remain a girl for ever and be still

A Girl.

Surely "It was a confused message for a girl to interpret" notes Forster. However, "In her own mind Daphne had no doubts: everything about being a boy appealed to her more...nobody realized quite how much Daphne genuinely hated being a girl." The middle sibling of three daughters, Daphne always wished she had been born a boy. She had a "Venetian" (du Maurier family code for lesbian) friendship with Ferdy, her teacher at her boarding school outside Paris. "The boy was out of the box and in love and, though she kept this hidden from all but Ferdy herself, she felt the greatest sense of relief imaginable" is the assessment of Forster. An adulthood friendship with Ellen Doubleday, the wife of her American publisher remained constant as two close friends. Only because of no reciprocity by Ellen - it remained a fantasy. A deep friendship evolved into a satisfying relationship with Gertrude Lawrence, the London stage actress who had been one of the young members of her late father's actress "stable" of lovers. Daphne maintained long commitments to all her friends; even when the "out of the box" aspect was over. Yet, there was never any "coming out of the closet."

In a fresh perspective, Forster weaves together a familial context whereby Daphne in her childhood exhibits little appreciation of her mother's obstacles yet admires her charming and flawed father. Her relationship with her mother turns more harmonious following her marriage to Frederick "Boy" Browning in 1932. A World War II hero with a long-distinguished career in the British Army, he was in later years appointed Treasurer to the Duke of Edinburgh. They received the Duke of Edinburgh and the Queen at "Menabilly." Browning and Daphne had a troubled marriage; yet each in his and her own manner remained devoted to one another. She disliked living in Egypt on his army posting. She ventured eastwards only up to Greece on holiday. Westwards, USA was more acceptable, it was also related to her literary career. She loved her house and home but was not into domesticity.

Her two daughters were brought up to be "little seen and not much heard." Again, relationships eased with their growing up. The birth of her son Kits exulted Daphne to proclaim: "I have done it at last...a son!...For seven years I've waited to see "Mrs. Browning, a son" in The Times." Poignant and revealing are the following lines in the "Afterword" by Forster: "To her children she was a mother who seemed happy and content. The revelation that she was so tortured for much of her life has been a shock...Daphne du Maurier's children warned me, when I began this biography, that I would find their mother 'a chameleon'... It may have tortured her to feel she was two distinct people but it also fuelled her creative powers: without 'No. 2', that boy in the box, there would have been nothing." Sometimes the dividing line between fantasy and reality remains dangerously thin. For Daphne du Maurier, "fear of reality" led her to retreat to "Menabilly," her venue for imaginative escape. Forster in her probing panaromic study of her celebrated subject, peels layers of personality traits and thus successfully releases Daphne du Maurier's emotional burden – "that boy in the box."

Significantly, Daphne du Maurier herself expressed her thoughts on biographies in a letter to her American friend Ellen Doubleday as early as in 1949. Daphne passed away forty years later in 1989. Daphne wrote: "What she detested were biographies that were 'stereo-typed, dull-as-ditchwater, over very fulsome praising.'" She realized the truth was often "hard for the family to take," but saw no point in biography otherwise. This sensitive and sympathetic biography by Margaret Forster would have been found acceptable if not welcomed by Daphne du Maurier.

Raana Haider is a bibliophile.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments