Do political parties support women's political empowerment?

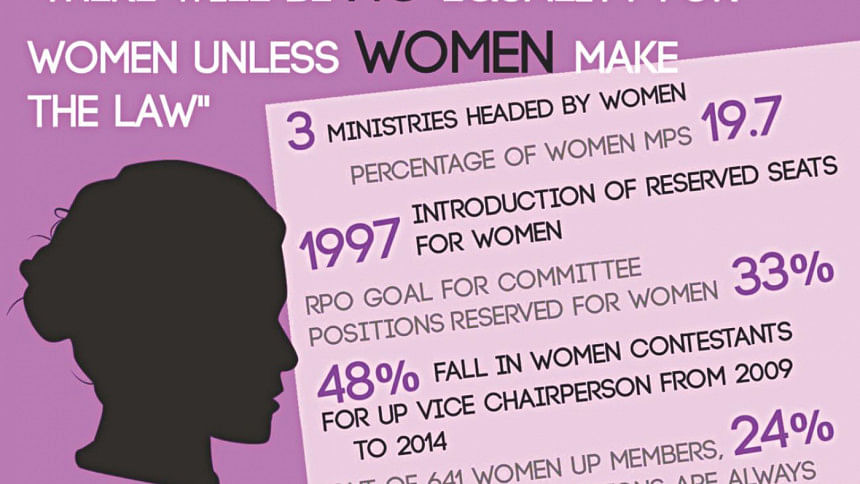

At first glance, one definitely has to appreciate the current key political positions held by women in Bangladesh: head of the government, leader of the opposition, Chief Speaker at the national parliament. Three Ministries, namely, those of Home, Agriculture and Women Affairs, formed under the 2014 Cabinet are led by women. In the 10th Parliament following the 2014 elections, there are 69 women parliamentarians of whom 50 are on the reserved seats and 19 have been elected directly, bringing the percentage of women MPs to 19.7 percent. However, the reality belying these impressive figures is that while women's number in political parties may have increased in quantitative terms, women are largely excluded from real decision-making processes. This is apparent from the fact that apart from a few important positions held by women politicians, the number of women in top leadership positions in the two major political parties remains small.

Although the third amendment to the Representation of the People Order (RPO) 1972 requires political parties to set the goal of reserving at least 33 percent of all committee positions for women including the central committee, progressively achieving this goal by the year 2020, in reality all major political parties have failed to incorporate gender equality in their party structure. A review of political party documents and election manifesto showed that women's representation within the two major political parties, Awami League and Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), is still very low. For example, the Central Executive Committee of Bangladesh Awami League has 12 percent or 9 women members while the BNP has 5 percent or 6 women members in its National Executive Committee. Men typically dominate leadership positions of these committees while women are given positions in committees on, for example, education, health, women and children because these are perceived as suitable for females as opposed to committees on economics, budget, and foreign affairs.

Additionally, while the Awami League Election manifesto aims to have 33 percent representation of women within the party by 2021, other political parties lack the aim of promoting women's participation in politics. In this regard, the quota-based system is yet to set indicators to measure progress towards this target. Furthermore, as the RPO does not mention any disciplinary measures against failure to meet this target, political parties perhaps feel they are under no obligation to include women in democratic politics.

What is happening on the local government front? The introduction of reserved seats in 1997 opened up doors for local women to engage in politics and contest for these seats at all tiers of the local government. Although this step proved to reach its objective initially, over the years, there has been a decline in women's participation in local government elections.

For instance, in the 2009 Upazila Elections, out of a total 2,900 female contestants, 481 women were elected to the reserved posts of Upazila Vice Chairpersons in 480 Upazilas. By contrast, in the 2014 election, the number of female contestants dropped to a total of 1,507 in 458 Upazilas, thereby demonstrating a 48 percent decrease over five years. In case of UPs, although the Election Commission figures of women contesting and winning UP elections in 2011 are not available, field experience of local government projects showed that the number of women contesting both reserved and general seats had decreased and the most common reason being cited was our country's political environment that favours muscle power and money.

The Dhaka Tribune (Feb 26, 2016) captured this scenario from Khulna's Dakope Upazila where the number of female candidates aspiring to contest the upcoming Union Parishad (UP) elections is record high but these candidates are reportedly under pressure to withdraw from contesting elections from their male rivals.

A research under the Local Governance Programme Sharique, which is promoting enhanced participation and representation of women in local government elections, indicates that negligence towards reserved seats exists even at the local chapters of major political parties. While parties give a lot of priority to and make the election campaign for UP Chairman's office highly structured to ensure victory, the same intensive support is not provided for the women members contesting reserved seats. In the words of a male UP member, the female wings of most political parties are not active at the UP level and neither do political parties raise awareness among women in this regard. As a result, local political activities remain mainly male dominated which further discourages women from engaging in active politics.

Aparajita – a project on women's political empowerment – conducted a study on Upazila Parishad reserved seat elections held in June 2015, before the party-based election system was introduced. The study carried out in 72 Upazilas of 40 districts across the country showed that following the declaration of the election schedule, the Upazila Parishad Chairmen, MPs, and local leaders of ruling party performed the primary selection of the candidates and final nomination. Many women candidates, who were competent but not affiliated with the political parties, were discouraged by local political leaders from submitting their nomination papers. In addition, it was observed that affluent candidates used money- as much as Tk. 5,000/ to 20,000/ per vote to influence the voters. Consequently, again, a good number of potential and committed female candidates may have failed to contest the elections due to lack of finances.

In fact, money and political backing are not the only obstacles that are hindering local women from joining politics. A stock-taking of publications and research on women's inclusion in political processes by Sharique (2014) identified that lack of capacity and inadequate resources are also bottlenecks that prevent elected women representatives from functioning effectively. Looking at the data on the education and experience of local government representatives, both male and female, it was evident that there are formal gaps in the desired qualifications which range from low literacy and lack of procedural knowledge to lack of experience of working within elected bodies. This is all the more true in case of local women as they are usually not well-acquainted with the complex administrative work required for filing election nominations. In addition, the system of reserved seats has its own limitations that come in the form of lack of unclear definition of roles and responsibilities of elected women representatives in the local government, vulnerable to discrimination, harassment and isolation by their male counterparts. Furthermore, reserved seat members do not have the same authority and resources as those elected through general seats. As a result, although women representatives gain access to the local government institutions through reserved seats, their influence in these public offices remains trivial. For example, a survey carried out by Khan and Mohsin (2008), among 641 UP women members in 13 districts across the country, found that 90 percent of respondents confirmed that they always attended Union Parishad meetings but only 24 percent reported that their decision was always considered.

Against this backdrop, the legitimate question is when the very basic institutional support and legal provisions remain missing, how much can Bangladesh claim to have made progress in women's political empowerment? More importantly, with a number of women's rights organisations and development-aid projects operating in the area of women's political empowerment over the years, it is difficult to tell who really deserves the credit for the progress – whatsoever – made in this sector.

With significant absence of women from the key decision-making bodies of political parties, it is clear that Bangladesh's politics indeed has women on the surface, but the decision-making process is still dominated by men. This subsequently raises the question as to how we can expect to promote the interests of women or further their causes in the prevailing political context borne out of a patriarchal structure.

Against this backdrop, the gender-based quota system needs re examination to measure its effectiveness in real and not just figurative terms to make political parties responsible for promoting certain basic principles such as gender equality inside the party leadership role and adopting practices of inclusive democracy. This is because if political parties fail to recognise the significance of women's political engagement and how it contributes to the whole process of governance and development, it would be unrealistic to expect Bangladesh to sustain its development targets that it has achieved in other sectors.

The writer is a staff member of BRAC Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD), BRAC University. The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not represent those of the institution she represents.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments