British Colonial Architecture in Bengal

The art and architectural style of Bengal has been rich and magnificent long before the British came to rule. It is evident from the ruins of various archaeological sites of Bengal that the art of building has been a long running practice here, since the earliest times of the region's history.

The ruins of Mahasthangarh, for instance, is proof that even during the ancient period, the builders were already working with highly developed techniques in making and use of bricks. In Somapura Mahavihara, deemed the largest Buddhist monastery in the Indian subcontinent, the orientation and proportions of the structure show the extreme sensitivity of the builders when it came to architectural techniques. Architecture, sculpture, terracotta and painting developed extensively during the Pala Dynasty rule from 8th to 12th century. In the Sultanate Period, Bengal had already developed a distinctive language, culture and architecture.

With the advent of the Mughals, political centralisation took place. For the region's architecture style, this meant that ideas and ideals were being enforced by the Governor of Bengal from Delhi. For the first time, the architectural tradition of the region was broken, which further continued with the rule of the British.

The next pivotal point came with the arrival of the Europeans. The Portuguese were the first to arrive in India for commerce and as missionaries. A century later, the Portuguese were followed by the Dutch, the British and the French. The Danes, the Armenians, the Greeks and the Germans also set up settlements in the region. However, colonial architecture became almost synonymous with that introduced by the British, since they occupied the largest territory.

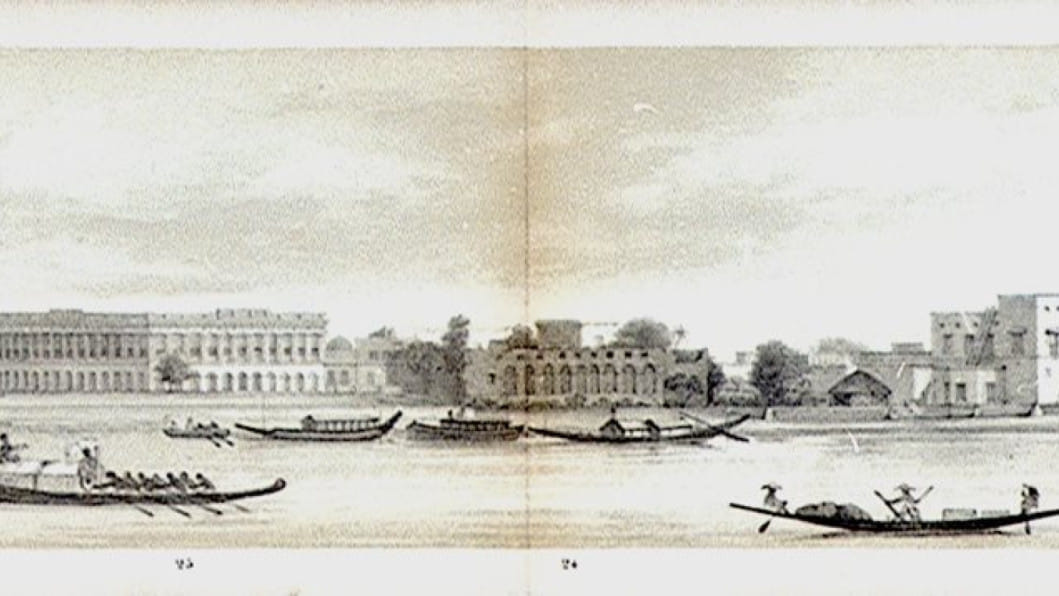

During the initial period of British occupation, Calcutta rapidly achieved importance as a city because of greater trading opportunities, owing to better communication by water. As a result, it remained the British capital of India from 1773 to 1912. Hence, it is no surprise that during the two hundred years of British reign, many of the architecturally significant structures, like the Belvedere House, the Writer's Building and the Victoria Memorial, were erected in West Bengal.

By definition, colonial architecture is the architectural style borrowed from a country of origin and then integrated into the structures located in far off regions. This particular architecture style evolved when colonists created a fusion by blending the architectural vocabulary of their country of origin with the design principles of the region they colonised.

Before we delve further into the grandiose and magnificence of British Colonial architecture, we must stop and reconsider the purpose behind building these structures. The architecture style of a particular time period is a reflection of a region's social standing and political power. As a display of power, Louis XIII built the Palace of Versailles, the Greeks built the Parthenon and the Mughal emperor Shahjahan built the Taj Mahal. Since the British considered themselves to be the successors of the Mughals, they too decided to use architecture as a symbol of power.

These chain of events began with the Indian Rebellion of 1857. When the Indian soldiers openly revolted against the British, the mutiny was mowed down by the colonists. The overthrowing of the last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar of India, marked the end of the Mughal Empire. Then it was time for the British to show they were the new rulers.

Historian and professor at the Department of History at University of California, Berkeley, Thomas R Metcalfe wrote in his book titled, An Imperial Vision: Indian Architecture and Britain's Raj:

"In the public buildings put up by the Raj, it was essential always to make visible Britain's imperial position as a ruler, for these structures were charged with the explicit purpose of representing the empire itself. Since they wanted to legitimise their rule, they decided to justify their presence by relating themselves to the previous rulers, the Mughals."

The colonial architecture style, thus, aimed to represent awe and power of the British Imperial rule in India. In order to be seen as powerful by the commoners, the colonists realised they must come up with a hybrid design style that the general public were already familiar with.

In the late 19th century, Indian British architects developed an architecture style that was a synthesis of Indo-Islamic and Indian architecture with borrowed elements of Gothic revival and Neo-Classical styles that were still in favour in Victorian Britain. Thus began the architecture movement known as Indo-Sarcenic Revival architecture—Sarcenic being a medieval Latin term for "Muslim".

At this time, the region which is present-day Bangladesh remained largely overlooked by the colonists, because of its lack of urbanisation and industrialisation. However, despite all this, a number of remarkable structures were built by the British, which remain notable today because of their architectural and historical significance.

When the British colonists changed their role from traders in 17th century to the new rulers in mid-18th century, their building art went through a series of development phases. Initially, British churches in Dhaka and its suburbs were built in the European Renaissance style, which was later also used for secular buildings. The next phase witnessed buildings with semi-octagonal or rounded corners and tall Doric columns become more favourable during the late-18th and early-19th century. The Classical orders—Tuscan, Doric, Ionic and Corinthian—also gained popularity in this region.

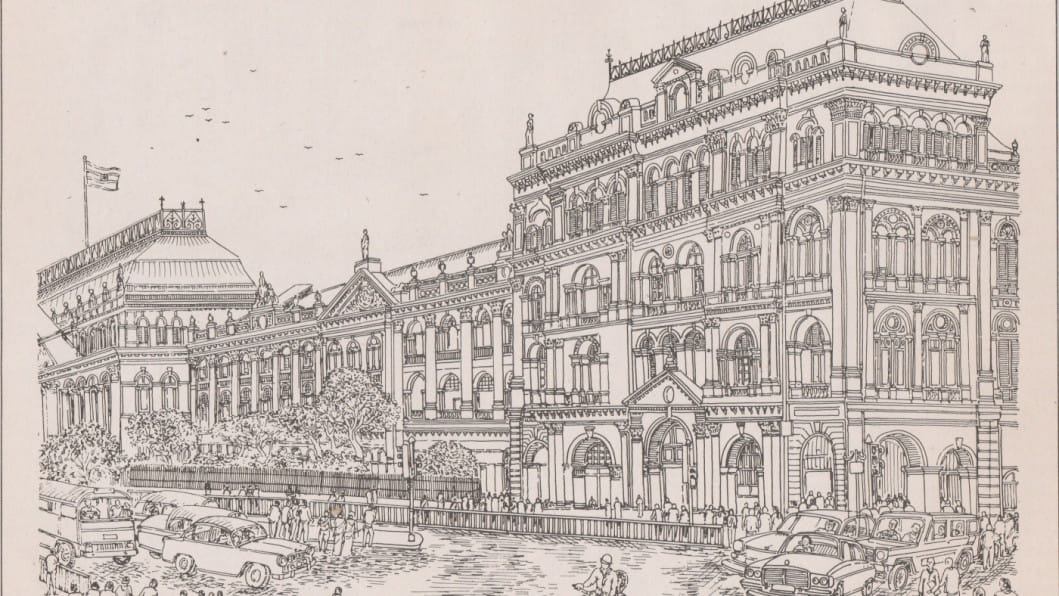

During the 19th century, some newer architectural elements were introduced such as the semi-circular arch, the triangular pediment built over the semi-Corinthian, Doric or Ionic columns and leaf-like motifs on plaster. The old High Court building is a notable example of this time period. In the wake of the partition of 1905, this building was designed originally as the official residence of the governor of East Bengal and Assam. The building has a typical European Renaissance style facade, and a triangular pediment over a large porch that is held up by Corinthian columns. The structure is topped off with a graceful dome that is supported by thin columns and piers in a ring formation. This is one of the colonial buildings in Dhaka built with little or no Mughal features in its architectural style.

These features can be still seen today in structures like Ahsan Manzil and the Greek Memorial located on the grounds of the Teacher Student Centre at University of Dhaka.

Following the first partition of Bengal in 1905, between the late 19th and early 20th century, a combination of the Mughal and European style of architecture made an appearance. This was carried out under the authority of Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of India from 1899 to 1905, who also happened to be a Mughal art and architecture enthusiast. Perhaps the most exemplary structure that defines this style would be the Viceroy's namesake, Curzon Hall. It consists of traditional artistry combined with modern design elements preferred by the Mughals such as horse-show and cusped arches and stunning domes. Appreciation of Mughal building style is also apparent in the red colouring, decorative brackets, deep eaves and domed chattris (terraced pavilion); all of this can be seen as borrowed elements from Diwan-i-Khas at Fatehpur Sikri, built by Emperor Akbar.

The building, which has been housing the Faculty of Science at University of Dhaka since its inception in 1921, became a reality due to Lord Curzon's dream of creating a magnificent town hall for the city. Even though his dream remain unfulfilled, the building still remains a key witness to some significant events in the history of Bangladesh, notably those during the Language Movement from 1948–56.

Other spectacular examples of this hybrid Mughal and European architectural style can be seen in Dhaka even today in Northbrooke Hall, Dhaka Medical College and Salimullah Muslim Hall.

Despite all the influences from European building styles, the colonial architecture era was able to successfully come up with a distinct architecture style, which was truly original on its own. This was the "bungalow", a remodelling of the deltaic hut. The bungalow exemplified the notion of living in nature inside a secluded hut covered by a roof, while being able to look at a distant horizon. Soon enough, the bungalow became a popular building style in the subcontinent and then afterwards, in other parts of the world.

It would be fascinating if we take a moment and look at the way architectural style developed since the earliest points of history in this region. Ever since the Mughal dynasty, this region has struggled with keeping its tradition and culture alive in their building style. With the introduction of colonial architecture, it was even harder to keep our roots intact. Architecture is supposed to give identity to a region. However, for Bangladesh, because of its complicated history, that has not been the case. Lack of historical materials makes the narration of the region's history difficult as well.

This is why it is of greatest urgency now to preserve all old structures that are still standing today. These works should be documented as much as possible by historians who are researching on these regions. Only then, maybe, we will reach a point where we have a clear understanding about this region's architecture, the complex history behind it and the consequences of that history on our building style.

Farhat Afzal is working as the Academic Associate at Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

1. Ahmad, Nazimuddin. Buildings of the British Raj in Bangladesh. University Press Ltd. 2000. Print.

2. Ahmed, Nazimuddin. Regionalism in architecture: proceedings of the regional seminar in the ser. exploring architecture in Islamic cultures ; sponsored by the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, Bangladesh Univ. of Engineering and Technology and Inst. of Architects, Bangladesh ; held in Dhaka, Bangladesh, Dec. 17-22, 1985. Edited by Robert Powell, Concept Media, 1985.

3. Ashraf, K. K., Saif Ul Haque, Raziul Ahsan. Pundranagar to Sher-E-Banglanagar : Architecture in Bangladesh. Chetana Sthapatya Unnoyon Society, 1997. Print

4. Ashraf, K. K., Islam, Muzharul, Saif Ul Haque. Introducing Bangladesh, A Case for Regionalism. Regionalism in Architecture. Proceedings of the Regional Seminar in the series Exploring Architecture in Islamic Cultures. Concept Media and Aga Khan Award for Architecture, 1985.

5. Campos, Joachim Joseph A. History of the Portuguese in Bengal. Janaki Prakashan, 1979. Print.

6. Datta, Kalikinkar. The Dutch in Bengal and Bihar, 1740-1825 AD. Motilal Banarsidass, 1968. Print.

7. Guaita, Ovidio. On distant shores: colonial houses around the world. Monacelli Press, 1999.

8. Mamoon, Muntasir. "Dhaka Smriti Bisritir Nagari (Dhaka the Memorable and Historical City)." Dhaka: Ananya (2000). Print.

9. Metcalfe, Thomas R. An Imperial Vision: Indian Architecture and Britain's Raj. Berkeley and London. University of California Press.1989.

10. R. Sengupta. "Historical Context Preservation and Interpretation of Colonial Gothic Architecture at Allahabad in India". Old Cultures in New World: Monuments in their Built Environment

11. Raja, Tousif. "Architecture as a symbol of power - SlideShare." Slideshare.net, 29 Sept. 2013, www.slideshare.net/Tousifra1/architecture-as-a-symbol-of-power.

12. Why the British creation of Indo-Saracenic architecture was a shrewd imperial move, Scroll.in, 20 January, 2018. <https://scroll.in/video/852107/why-the-british-creation-of-indo-saracenic-architecture-was-a-shrewd-imperial-move>

13. "The History of Curzon Hall - Bangladesh Blog | By Bangladesh Channel." Bangladesh.com - Bangladesh Channel, www.bangladesh.com/blog/the-history-of-curzon-hall.

Comments