Safeguarding transfusions: recognising and reducing TA-GVHD risks

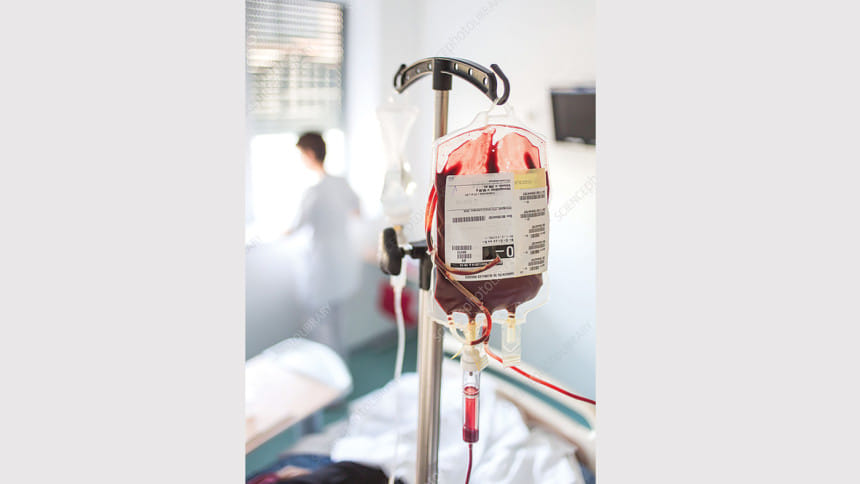

Imagine this scenario: you need an urgent blood transfusion, and your brother is present. Thinking it's safest, you use his blood without consulting a qualified haematologist. Within days, you develop a purplish skin rash, fever, and nausea. A visit to the doctor reveals a devastating diagnosis: Transfusion-associated Graft-versus-Host Disease (TA-GVHD)—a rare but often fatal condition with a mortality rate of 87–100% (NCBI).

Taking blood from a first-degree relative increases the risk of TA-GVHD due to partial human leukocyte antigen (HLA) matching. This similarity allows donor T lymphocytes to recognise the recipient's body as foreign and attack vital tissues. To prevent this, it's advised to take irradiated blood from non-relatives—easily available at blood banks.

Although rare, TA-GVHD is almost always fatal once it occurs. There's no effective treatment except for a stem cell transplant, which is rarely feasible in time. Symptoms typically develop 2 to 30 days after transfusion and include skin rash, jaundice, fever, nausea, fatigue, diarrhoea, liver abnormalities, and pancytopenia—the hallmark sign.

This condition occurs when donor T cells mount an immune attack on the recipient, damaging the skin, liver, gastrointestinal tract, and bone marrow. Immunocompromised individuals are especially vulnerable, as their weakened immunity cannot counter the attack. Blood components that may carry T lymphocytes—whole blood, PRBCs, platelets, or fresh plasma—can all potentially cause TA-GVHD.

To simplify: your body has a security system. When you receive donor blood, it may bring in its own "security guards"—the donor's immune cells. If these new cells see your body as a threat, they launch a fatal internal attack instead of helping.

Death from TA-GVHD usually occurs 1 to 3 weeks after symptoms begin, due to overwhelming infections. Because of the lack of effective treatment, prevention is essential. Here are key preventive measures:

Irradiation: Gamma irradiation of blood components is the primary method to inactivate donor T-lymphocytes and prevent TA-GVHD.

Avoid blood from close relatives: Blood from siblings or cousins should be strictly avoided due to increased HLA similarity, which raises TA-GVHD risk.

Use standardised blood banks: Choose facilities that follow strict guidelines for screening and processing blood products.

Special precautions for immunocompromised patients: These individuals face greater risk and require irradiated, carefully screened blood.

Leukoreduction: While not sufficient alone, reducing white blood cell content in blood products lowers the risk. Pathogen reduction technologies can also help.

Avoid consanguineous marriage: Reducing genetic similarity within families can lower the risk of HLA matching complications in transfusions.

TA-GVHD may be rare, but its impact is devastating. Misleading depictions in media, such as those seen in Bangladeshi films, can foster dangerous misconceptions during emergencies. Awareness and proper transfusion practices are crucial.

Further research is ongoing to identify viable treatments. Until then, recognising the risks and taking preventive steps remain the best defence.

The article is compiled by Jannatun Nayma. E-mail: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments