Of war's taboo front

I think I'm pretty lucky to be

adopted and brought to Canada

I get a lot of choices and I know

my mom loves me a lot.

These lines are from a Mother's Day poem, "How I got Here", composed by 12-year-old Onil Mark Mowling in May 1984 for his class to share his life story.

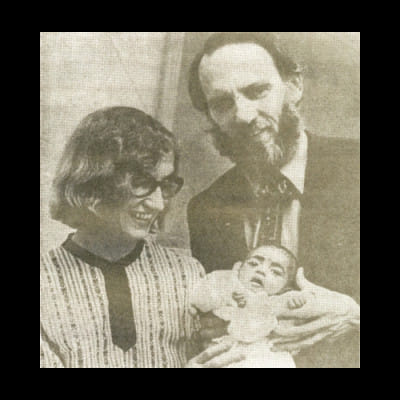

He was among the 15 Bangladeshi war babies embraced by their adoptive parents in Canada in 1972.

Mustafa Chowdhury, a Canadian citizen of Bangladeshi origin, for the first time has brought to light a key document that contains the names and dates of birth of eight female and seven male war babies, names of their adoptive parents and permission for their adoption.

Signed by M Sharafatullah, deputy secretary of the labour and social welfare ministry, on July 17, 1972, the permission was considered the "group passport" of the 15 to leave the country for Canada.

The document prompted Mustafa to look for more information in the National Archives of Canada as well as the archives in Geneva, London, New York and Dhaka.

A retired federal public servant in Canada, Mustafa spent over 20 years conducting a research through face-to-face interviews of the children and adoptive Canadian couples, and collecting relevant documents.

Based on his findings, he later wrote a book, "Ekatturer Juddhoshishu: Obidito Itihash", published by Academic Press and Publishers Library (APPL) in Dhaka early this year.

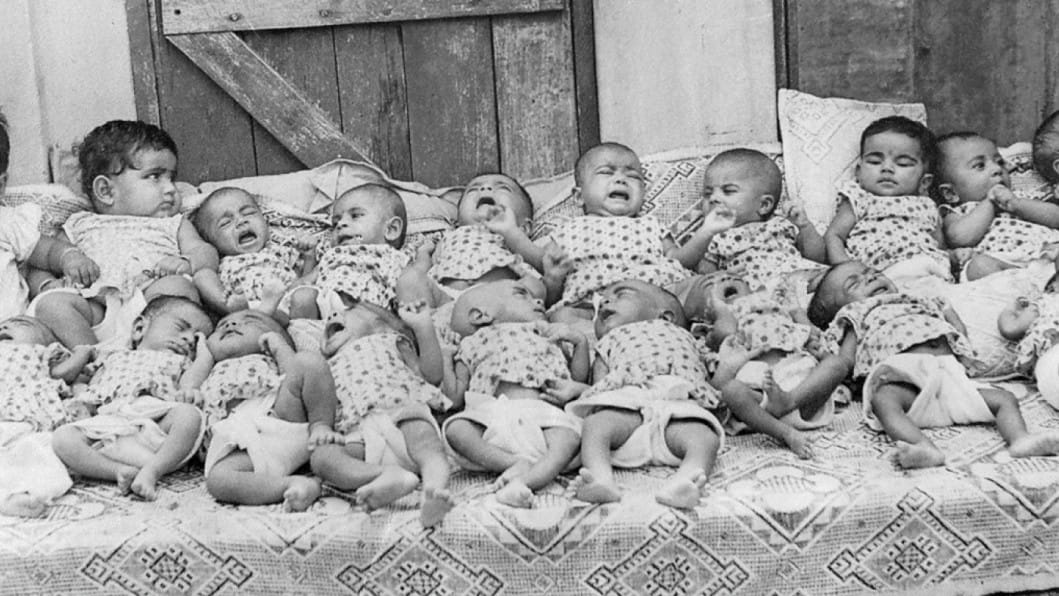

The 15 war babies, out of 21, were flown to Canada from Dhaka's Islampur-based Mother Teresa's Missionaries of Charity (Shishu Bhaban), the then statutory guardian of war babies, with a Canadian team led by Reverend Fred Cappuccino and his wife Bonnie Cappuccino.

The rest of the babies, who seemed not medically fit for overseas travel, ended up dying within days after the 15 children -- the first contingent of war babies -- left Bangladesh.

The war babies reached Canada on July 20, 1972. They are today in their early forties and contributing members of their society as Canadians of Bangladeshi origin.

In his interview, Ryan Badol Good, one of the adopted, told Mustafa, "I have two mothers -- one calls me Ryan, and the other calls me Badol. The one who calls me Ryan, I have known all my life. The one, who calls me Badol, I have never met. I was born in Bangladesh to the mother who calls me Badol. Three weeks later, I was born in Canada to the mother who calls me Ryan. A Pakistani soldier raped the mother who calls me Badol. I am a war baby."

Drawing a parallel to his own birth and the birth of Bangladesh, Badol said, "We [the war children and Bangladesh] are both babies of a very tragic but important war.

"I wish I could have found my birthmother and let her know how deeply sorry I am for her suffering and that something good came out her sacrifice."

Lara Jarina Morris, another member of the batch of 15, said, "My [adoptive] family has always treated me as one of their own even though we are not genetically connected. I have never been made to feel alienated or isolated just because I don't' look like any members of my family."

Talking to The Daily Star, Mustafa Chowdhury said their lives were not only saved but were enhanced due to the unconditional love and affection with which they were embraced. From the testimonies of the war babies, he concluded that their story of adoption is indeed a success story, something to celebrate.

The fate of the country's other war babies and their exact numbers are still unknown.

Citing newspaper reports, Mustafa Chowdhury in a write-up said between 300 and 400 children were born on the premises of 22 Seva Sadans (delivery centres or clinics) in Bangladesh.

He also mentioned that the Executive Director of the Canadian Unicef Committee following visits to both occupied Bangladesh and independent Bangladesh, where he had held discussions with representatives of the League of Red Cross Societies and the Unicef personnel, reported to headquarters in Ottawa that the estimated number of the war babies was in the neighbourhood of 10,000. This is the largest number quoted in any record that made reference to the birth of the war babies in 1972.

A report of The Dispatch published on December 13, 1973, said nearly 200 war babies had been adopted by North American and European families.

A report published in The New York Times on March 5, 1972 said, "Some raped women have been sent away by their parents, some even by husbands, not to return until the birth and not to return with baby."

Quoting Dr Geoffrey Davis of the International Abortion Research and Training Centre in London, who had visited villages throughout the country to instruct physicians on abortion techniques, The Times in another report on May 12, 1972 said the war babies were disposed of by drowning or other means.

The war babies were killed to erase the identity of their mothers as raped women from the society.

About the negative societal attitude, Mustafa in his book described that the birth of the war babies, conceived as a result of rape by Pakistani soldiers or collaborators, was seen by Bangladeshis as morally repugnant; hence the infants thus born were considered and looked upon as the "unwanted" babies in Bangladeshi society.

The problem with regard to the war babies thus became complicated due to the simple fact that they were not accepted by Bangladeshis who remained both indifferent to and indignant towards such "disposable" babies. This fact had at once clearly categorised them as "undesirable;" as well, it also instantly subjected them to ostracism during the time they were born in 1972.

Describing the social stigma centring the war babies, Hameeda Hossain, a women leader and social worker, in an interview said, "I once witnessed a scene where a young woman who had given birth to a baby in December had to hand her baby over to a British woman…The mother had wanted earlier to abort the child and even tried to commit suicide. But had looked after the child and grown fond of it. As she handed the child to the foster mother, she wept and seemed unwilling to give it. But she was told that it would not be possible for her to take the baby back to the village."

American journalist and author Susan Brownmiller in her book "Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape" quoting three sets of statistics variously, stated that two lakh, three lakh or possibly four lakh women were raped during the war and mentioned that about 25,000 women found themselves pregnant after the war. Quoting a physician, she said about 5,000 women had managed to abort their babies by various medically unsafe methods.

Citing another statistics, Dr Bina D'Costa, in her article, said some 1.5 lakh to 1.7 lakh women had abortions done before the abortion programme was started by the government.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments