The Kajoli model learning with laughter, growing with joy

"Who will pick up the duck's photo?"

The moment Rafia Sonamoni posed the question to a group of 26 children, four eager hands shot up, accompanied by excited shouts of, "I will!"

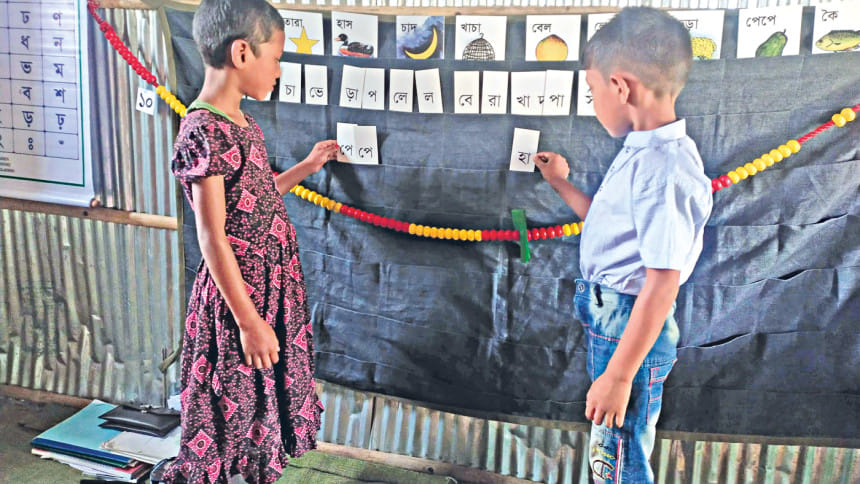

Among them, Partha Roy was the most enthusiastic. He was chosen to pick the card with the duck's picture from a large board made of black cloth with pockets. Each pocket held a card — one side displaying a word and the other featuring an image of the word alongside the text.

Sprinting towards the board, the five-year-old scanned the cards quickly and selected the one with the duck's photo. Turning to his classmates, he stretched out his hand with the card and asked, "Friends, have I picked the duck's photo?"

"Yes!" the children chorused, clapping enthusiastically.

Rafia, smiling warmly, thanked Partha and then guided him towards the next challenge: assembling the word. She asked him to find and arrange the individual letter cards to spell "duck."

Partha turned back to the board and began searching another row of pockets with letter cards. Carefully, he picked up the four letters, arranged them in the correct sequence, and then turned to his friends, asking, "Friends, have I spelt the word correctly?"

Another round of applause erupted, confirming his success.

This joyful activity unfolded at one of the early childhood learning centres in a remote village in Nilphamari, where education is woven with play, laughter, and discovery. Established under the Kajoli Model, an initiative of Research Initiatives, Bangladesh (RIB), these pre-school centres reimagine learning as an engaging and interactive experience for children from marginalised and disadvantaged backgrounds.

Here, young learners, mostly between four and five years old, do not need to bring textbooks, exercise books, pens, or pencils. Instead, they grasp the fundamentals of reading, writing, and counting — all in a joyful setting that nurtures their curiosity. They also learn to recite rhymes and songs along with some basic etiquette, hygiene, and social interaction through playful, hands-on activities.

"I like this school very much; it's fun. We study, we dance, play and eat together," Partha said, wearing a smile.

A farmer's son from Bahalipara village in Ramnagar union, Partha used to roam around the village and help his father in the fields before the centre was established four months ago. But one day, his mother heard about it from a neighbour and decided to enrol her son — a decision that soon yielded remarkable results.

"I was surprised to see him [Partha] speak some English words and recite an English rhyme. He learnt so quickly, which was beyond my imagination," said his mother, who is in her early 30s.

Rafia Sonamoni, who has been teaching the children for the past four months, noted that children are naturally drawn to the centre because learning here is fun. "The approach is quite easy and interactive, and that is why kids learn so fast."

The centre was set up on an open veranda at Rafia's home. She finds it rewarding when guardians express their happiness at seeing their children read and write so quickly.

"Most of the guardians are very enthusiastic about their children's education here. They are particularly amazed to see their kids learning Bangla and English without having any textbooks or khata," said Rafia, a first-year honours student at Nilphamari Government College.

The Daily Star recently visited eight such centres, popularly known as the "Kajoli Model", in Nilphamari and witnessed how a remarkable initiative is shaping early education and empowering young learners with essential literacy skills.

LEARNING THROUGH PLAY: THE KAJOLI MODEL

The journey of the Kajoli Early Childhood Learning Model, developed by RIB, began in 2002 following the successful completion of a unique action research project in Kajoli, a village in Sreepur Upazila of Magura district. In January the following year, 10 centres were launched.

The main objective was to develop an early childhood model that makes education accessible and attractive to children from marginalised and disadvantaged communities in Bangladesh, ensuring pre-school education is available at very low or no cost.

"Many parents from disadvantaged families believe that education is difficult and expensive, and meant for wealthy families. We decided to break this misconception," Dr Shamsul Bari, Chairman of RIB, told The Daily Star.

Through RIB's research, he said, they decided to do away with traditional textbooks, paper, and pens in the Kajoli Model because these involve costs. "At the same time, we wanted to instil in children the idea that learning is fun," said Bari, who conceived the model through his extensive experience of teaching Bengali at several universities in the US.

Under the model, each learning centre has 26 children, a teacher, a large pocket board, pocket cards with pictures and letters (for Bangla and English), Ganitmala (for mathematics), a blackboard and chalks. The best feature is that the Kajoli Model is entirely run and managed by the local community.

Unlike the traditional system of memorising letters, the teachers first show the children pictures of different objects and animals with their names in Bangla and English on them, and the students have to match them with the corresponding pictures. They learn spelling, pronunciation, and make words by assembling separate cards (known as broken cards).

For mathematics, RIB developed Ganitmala, a hands-on learning tool designed to make foundational maths concepts engaging for young students. Using a string of 100 beads, it helps children grasp essential arithmetic operations — counting, addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division — through visual and tactile learning.

By manipulating the beads, students develop an understanding of numbers and patterns. For example, they can physically group beads to see how multiplication works, or slide them apart to explore subtraction.

"All we wanted was to make education feel like fun. Children see the pocket board activities as fun and games and therefore do not lose interest in learning. This method fosters curiosity and builds confidence," said Dr Bari, a former top-ranking official of UNHCR.

"After attending classes for a year, students have a solid foundation and are fully prepared for primary education at local schools," he added.

Since its inception 23 years ago, nearly 99,000 children across the country have received pre-primary education through Kajoli Model centres. What started with just 10 centres grew to 200 over the years. However, the numbers declined due to the impact of Covid-19. Today, 87 centres remain in operation — most of which are located in the northern districts, according to RIB.

COMMUNITY OWNERSHIP AT ITS CORE

What truly sustains the Kajoli Model over time is its deeply rooted, community-driven structure. These centres are not dependent on external aid; rather, they thrive on the collective efforts and commitment of the local community. RIB's research found that external aid, such as foreign donations, could create dependency on outside support and thereby undermine the model's sustainability.

From funding and management to physical labour for constructing the learning spaces, the responsibility of running and maintaining the centres rests entirely with the people, with mothers playing a pivotal role in this model.

The centres are set up in spaces offered by the community — whether it's a spare room in a home, a veranda, an unused space in local public buildings, or a hut built by the community. They arrange seating for children with floor mats and contribute their own money to ensure teachers receive an honorarium.

Teachers play a crucial role in translating the concept of 'learning through fun' into reality, and the community chooses someone who has affection and good rapport with the children. A woman or teenage girl from the locality with some basic education (reading, writing, and counting) is preferred to be the teacher.

DRILLS, DANCE AND SONGS: A SYMPHONY OF LEARNING

Apart from learning to read, write and count, the children learn to recite nursery rhymes and poems, dance, sing songs, and tell stories. RIB developed a set of English drills so that the students could speak in English through structured practice.

Such a drill was witnessed at a centre in Ramnagar Bazar, Nilphamari Sadar.

Leading the exercise was Kotha, who guided her fellow students through the drill, encouraging them to follow her lead.

With expressive gestures, she pointed to her classmates and said, "I am," "You are," "He is," "She is." In perfect unison, her peers echoed her words.

Five-year-old Shartok then took the lead: "I am a boy," "You are a girl," "He is a boy," "She is a girl," with the class repeating each sentence after him in rhythm. The centre, set up in an unused room of a school abandoned a few years ago, resounded with the enthusiastic voices of the lively children.

Taking the floor next, Ferdousi Begum, the teacher of the centre, introduced a new set of phrases: "We are", "They are", "You are", "The boys are." She then said: "This is," "That is," "These are," "Those are." Her students followed along, their voices blending in a rhythmic chorus.

She then showed her students a pen. The children said in unison: "I have a pen."

"Students at the centre learn faster thanks to the learning techniques," said Ferdousi, who has been teaching for the past four years.

She said the children's eagerness was unmistakable.

As a demonstration, she asked her students to write down their names. They excitedly grabbed chalk and rushed to the blackboard attached to the wall, putting their learning into action.

At a centre in Babupara of Ramnagar, children started offering salam as soon as this correspondent, along with a team of RIB members, arrived.

As their teacher, Pravati Roy, asked them to recite a rhyme, the children took no time to begin. "Twinkle, twinkle little star, how I wonder what you are…" they chorused, using hand motions along with the teacher.

In evaluating the achievement of the children after completing one year, teachers check whether the students can read, write, speak, and count.

Teachers at nearby schools have reported that former Kajoli students adapt quickly, show strong foundational knowledge, and actively engage in class.

Jahangir Alam, headteacher of Uttar Ramnagar Government Primary School, said that students from Kajoli Model centres perform well once they enter primary school, often outperforming peers who did not attend any pre-primary programme.

"This is because they gain a strong foundation at the Kajoli centres," he said.

POWERED BY MOTHERS, SHARED WITH LOVE

Sumona Roy, a mother from Bashdaha village in Laxmichap union of Nilphamari, said that parents contribute to the teachers' monthly remuneration based on their financial ability, ensuring that the centre remains operational.

"We try our best to contribute. In the early days, each of us would give Tk 10 to Tk 15, as much as we could afford. Now, we have managed to increase it to Tk 20 to Tk 30," she said.

One of the most impactful features of the Kajoli Model centres is the mid-day meal, an initiative led entirely by the mothers. Mothers take turns cooking and serving khichuri, a nutritious dish made with rice, lentils, and vegetables, once a month for all the children.

With 26 students and typically 26 school days in a month, each mother is responsible for providing the meal once a month. Since this is equivalent to cooking daily for her own child, she is motivated to contribute, knowing that her child will receive a meal the rest of the month through this collective effort.

"Only one kg of rice, half a kg of lentils, and one kg of vegetables are enough to feed all the children each day. So, it's no burden. After all, we are feeding our own children," said Sumona Roy.

Dr Bari said that in many rural areas, children often arrive at school without having breakfast, making it difficult for them to focus and remain active throughout the day.

The mid-day meal alleviates their hunger and keeps them energised, he said, adding, "This practice of providing food gives the mother a sense of ownership."

Ranjana Akter, a teacher who runs a centre on the veranda of her in-laws' home in Paschim Hazipara area, credits the collective efforts of the villagers, especially the mothers, for keeping her centre running successfully for the past five years.

"Without the wholehearted support from the guardians, I would not have been able to run the centre," she said.

Ranjana's father-in-law, Abdul Kader, believes there is nothing more noble than children learning, and he takes great pride in being part of this meaningful effort.

"We will keep our centre going," he said with conviction.

CHAMPIONS, COMMITTEES, AND COLLECTIVE ACTION

Another major participant in the Kajoli Model is the 'champion'. The champions — many of them local representatives or enthusiastic youths — promote the cause of the centres to the local community. He or she secures the support of the community to ensure that the centre runs smoothly.

Nazrul Islam is one of them. He said he immediately agreed to be a champion after witnessing children confidently speaking English at a centre.

"What amazed me was how eager the children were to come to the centre. They learn together, share meals, and genuinely enjoy the day," said Nazrul, a resident of Paschim Hazipara in Ramnagar.

Nazrul, who is in his final year of honours at Nilphamari Government College, said, "It's a great cause. Children from poor families get the opportunity to acquire basic learning skills at no cost, with active involvement from their families and neighbours.

"Most importantly, we, as members of the community, play a role in this noble effort, ensuring its success."

All Kajoli Model centres are overseen by a dedicated committee that ensures their smooth operation, manages resources, and makes necessary arrangements to sustain the centre's activities. Each centre operates six days a week, conducting daily sessions for around four hours.

Girimala Rani Roy is the head of the committee at one centre in Ramnagar union.

Around two years ago, she said, a champion came to their home and requested them to open a centre. "After hearing everything, I agreed to run the centre at my home. One of my grandsons is a student here," she said.

The Kajoli Model stands as a testament to what is possible when education is driven by empathy, rooted in community, and shaped by the needs of the learners.

Dr Bari said, "The Kajoli Model thrives because it fosters a sense of ownership among the local people. When communities take charge of their children's education, the model remains resilient."

"If every village could have such a centre, millions of children would have begun schools not in fear, but with excitement and confidence," he said.

As Kajoli Model centres continue to grow organically without external funding, the need for a dedicated foundation has emerged to ensure their long-term sustainability.

"We've come this far through community ownership and personal contributions," said Dr Bari. "But to reach more children and sustain our momentum, we need a more structured foundation—one that can effectively oversee the centres and maintain coordination."

Wasim Bin Habib is the Planning Editor at The Daily Star

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments