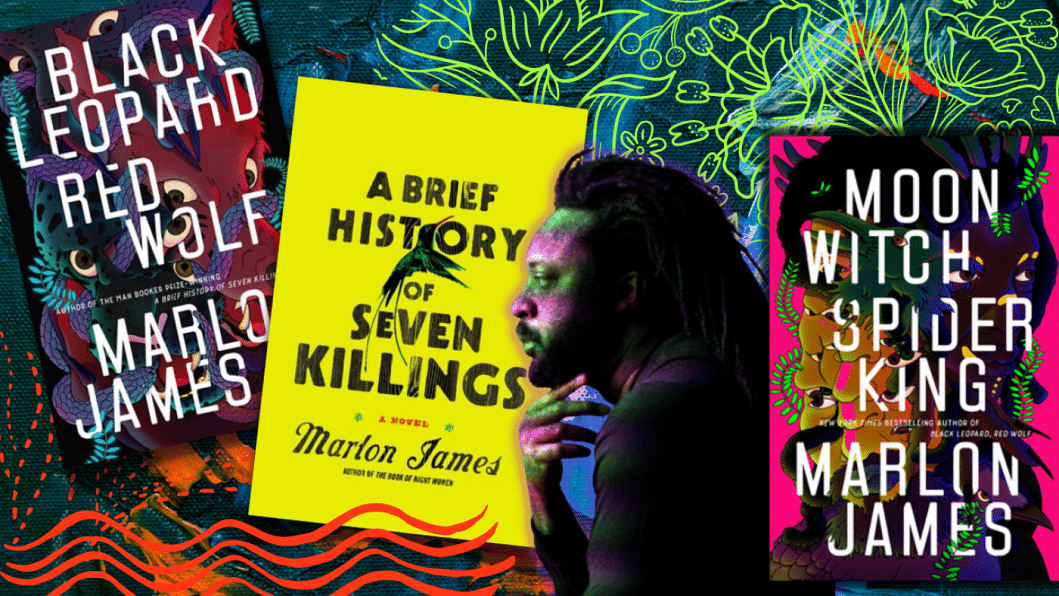

The dangerous game of Marlon James—Can genre fiction be great literature?

Salman Rushdie often recalls that early on in his career, he realised that he could not write about India in "cool, Forsterian English" a la A Passage to India, because India was not cool, she was hot, and her story needed to be told in a new kind of hot, grimy, chaotic language.

This early confidence in this newly forged voice, made flesh and blood through the smart-mouth narrator Saleem Sinai, allowed him to put down on paper the piece of literary audacity that was Midnight's Children (1981). If Rushdie back then knew how to write hot, today Marlon James—a self-professed Rushdie fan—turns the oven up a few degrees, and comes close to burning down the kitchen … along with the paternalistic authority of the Anglo-American literary world in dictating what an English novel should look and sound and smell like.

James, like Rushdie, is a supremely skilled stylist of English prose in all its forms—and he is perfectly capable of writing in the straight and narrow, that is, if he wants to. But he doesn't want to. This defiance, along with his hypnotic skill, blinding originality, and willingness to break every rule in the book makes him a force impossible to ignore.

With a Booker prize behind his back and two-thirds of the way into a fantasy trilogy somewhat superficially dubbed an "African Game of Thrones," Marlon James is, right now, the hot one to watch in the game of novels.

Tear down this wall

When James won the 2015 Man Booker Prize for his third novel A Brief History of Seven Killings (2014), he was on top of the world, and could have chosen to do just about anything next. Fresh off the Booker win, with all doors opening for him, he turned in a direction few could have predicted, except a handful of insiders who were already aware of James's childhood interests—high fantasy.

From a very traditionalist point of view, this looks like not just a mere thematic departure, but a breaking of the barrier between that which is somewhat snootily referred to as "literary fiction" or simply "literature," and "genre fiction," the latter understood to be belonging to a lower order of entertainment, i.e. thrillers, romances, horror, science fiction, fantasy, in other words, books written quickly to tell an absorbing story but written without much style or grace.

A piece of genre fiction has a clear and utilitarian purpose—you have that specific itch, for, say, a spy thriller, you purchase a Tom Clancy, digest it in the morning, forget it by evening, and even without a doctor's prescription, the book can do no harm.

Authors of genre know exactly the Faustian pact they make when they enter the genre game: Your books will sell and make money, perhaps even get lucrative TV or film deals, but they will never be mentioned by your high school English teacher as required reading, graduate students will not pore over your career to write dissertations on meaning and truth that can be decoded from your work, and you will never be up for a Nobel prize.

Genre titans like George RR Martin, JK Rowling, and Dan Brown will have to cry into their truckloads of cash with the knowledge that the literary establishment will never see their work as great literature.

Or so went the narrative.

Recent years have seen a gradual erosion of this wall separating genre and lit-fic. Writers like Yann Martel, Margaret Atwood, and Eleanor Catton, all Booker winners and therefore qualifying as writers of "literature," have been at one time or other criticised as populists of a lesser order, or at best as slightly-elevated genre writers who play a delicate dance.

These criticisms have been losing their power. After all, novels are meant to be read, pages are meant to be turned, so is it really so bad to be accessible and easily digestible? Catton, to be fair, is not "easy" (simply due to the size of her book), but her Booker-winner The Luminaries does, sort of, fall into the murder mystery-romance category.

Still, so far, unstable as the border between the two worlds may be, there has been a semblance of one. Marlon James is the next step to tearing it down—here I truly believe the novel is having a very special moment. Unlike previous writers who flirted with the blurred lines, James's transgression is more complete, and without apology.

He is playing a dangerous game: By tossing Black Leopard, Red Wolf and Moon Witch, Spider King at the literary establishment, and promising a third book in the pipeline, James seems to be saying to the establishment, to the same generous folks who once gave him the Booker and propelled him to the stratosphere: Go ahead and say this is not literature, I dare you.

Bright star, dark star

Black Leopard, Red Wolf (2019) and Moon Witch, Spider King (2022) are the first two books in James's Dark Star trilogy. The third of this dazzling series, tentatively titled White Wing, Dark Star should be coming out soon (unless James decides to pull a George RR Martin and leave us all hanging). The rights to the series for a TV adaptation have already been purchased by Michael B Jordan, and if done right, could become the most exhilarating re-invention of prestige TV since the pre-finale seasons of Game of Thrones. But that is a question that will have to wait. For now, we concern ourselves with the novels.

So, what is Dark Star about? Hoo boy. Here we have a sprawling fantasy epic set in Africa. But when is the story taking place? Is it pre-colonial Africa? Is it a parallel Africa that might have been if not for the colonial overlords cutting up the territory into irrational chunks? This is not clear.

We do see, however, immensely wealthy cities in this universe, cities like Dolingo which are technological marvels (harbouring dark secrets I will not spill). There is magic, enchanted forests, and people with special powers. There are shapeshifters and immortal (?) tyrants and doors that can transport a person vast distances in the blink of an eye.

There are vampires and river dragons and grass trolls and water nymphs and a long roster of creatures too bizarre to explain or visualise. The narrative is relentlessly violent, disturbing, raw. Child murder, torture, sexual abuse—all of this is there in its naked brutality. Furthermore, because of his fantasy canvas, James is able to dial it all up. Take whatever is possible in our world, and transpose it to a fantasy Africa where your (James's) imagination is the limit.

In the first book, we follow a hunter known as Tracker in search of a boy who may or may not be dead. (The book begins with the line: "The child is dead. There is nothing left to know" but we know better than to trust opening lines). Along the way, he meets a cast of characters and forms uneasy alliances. He meets Bunshi, a sort of mermaid (not quite), and Sogolon, an extremely old witch with an axe to grind. They are all playing their own game, and there is danger at every corner. The story is told from Tracker's point of view, and the language is earthy, brutish, and completely disregards the rules of the English grammar books we memorised in school.

In A Brief History of Seven Killings, James wrote large sections in patois, and others in a more standard BBC English, depending on which character's voice it was. Furthermore, the level of patois varied from character to character. Here, James uses a kind of English that can be thought of as African, but also his own. It is a fantasy after all, so here he allows himself to invent the idiolect as he goes along.

The second book, not a sequel that simply picks up from the first, but not a direct prequel either, is told from the point of view of Sogolon, and in her voice. The language here is as challenging as the first, and it demands attention. Details are fleshed out, gaps are filled in.

The story of the missing boy is different from the point of view of Sogolon, and it is only towards the end of the book that the story merges with that of our old friend Tracker. The violence in the second book is less graphic than the first, though the emotional violence is searing, and new depths are plumbed when it comes to love, loss, and the insatiable desire for revenge.

This series has been described as an African Game of Thrones. Fair enough—there are kings and princes, and there is the question of succession and legitimacy. And like George RR Martin's epic, James's world also asks the question: Who wields power, and why? In a world of never-ending bloodshed, can the cycle ever be broken?

There does seem to be a highly moral core to this bleak and blood-soaked epic. But James does not make it easy for us. As we follow Sogolon's brutalised life and witness every way in which she has been wronged, it is hard not to take her side, but then, not all of her actions have been condoned either.

All is permitted?

A Brief History of Seven Killings was an epic surrounding the assassination attempt on Bob Marley. Many have pointed out that the story is neither brief, nor a "history," nor does it feature only seven killings, because far more people meet their sticky ends in this book. The canvas was vast, with characters ranging from street-level drug dealers to CIA operatives, all tied together in a tale of intrigue and double-dealing. The book challenged the reader, and will certainly not be everyone's cup of tea. But overall, it worked.

What about the Dark Star trilogy, though? Superlatives for the first two books abound, and I myself am guilty of all-too-effusive gushing. But does it work as a whole? It is too soon to tell.

The fact remains, a lot of things in the book probably make more sense inside the author's head than are communicated clearly, and the inventiveness of the language and world can be rough going for the reader.

The style of narration sometimes also makes it hard to parse the timeline. Is this happening now? Is this a flashback? Who exactly are these creatures again? And are they creatures that incite deathly terror or are they merely moderately disconcerting? As is often the case with fantasy, it can get hard to keep track, and this is all the more the case here. A lot will depend on the third book, and whether or not James can stick the landing is still a question up in the air.

Even more than A Brief History of Seven Killings, the reader does get an "all is permitted" sense from James in his fantasy writing. Though he lives in the United States at present, as a gay man born and bred in Jamaica, he is no stranger to forging his own truth and standing his ground in an intensely homophobic culture. The dark history of the slave trade looms over the history of his home country, and urban neighbourhoods are plagued by street violence and drug culture.

James seems to have always known that if he wanted to break out of that cycle, and make his voice heard – not as an establishment stooge or an Anglo-American lackey, but as himself—he would have to create a new style, break all the rules, and stand his ground. In this regard, he stands as part of the same irreverent tradition as Salman Rushdie.

Not everyone will like him. Not everyone will be willing to accept a fantasy series as high literature. Not everyone will be enamoured by his disregard for English grammar. Furthermore, the existing community of fantasy geeks may feel alienated, and refuse to embrace him. And Marlon James, the bright star for now, knows he is playing a dangerous game.

But he stands to win big.

Abak Hussain is a journalist and former editor of the Editorial and Op-Ed pages at Dhaka Tribune. He is a director of Talespeople, a creative start-up, and a winner of the Iceland Writers Retreat Alumni Award.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments