Food, Fast: Behind delivery boom lies a workforce without rights or recognition

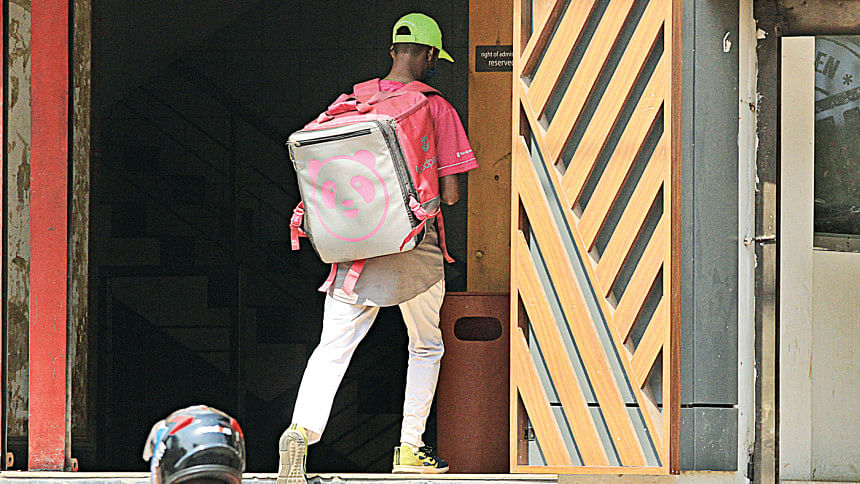

With a signature pink Foodpanda delivery bag slung across his shoulders, Abdul Kader pedals tirelessly through the congested and pothole-riddled roads of Dhaka. Whether it's a scorching summer afternoon, a drizzling evening or tempestuous night weather, he navigates the city's relentless traffic, weaving between rickshaws, buses, and motorbikes to deliver meals on time.

For thousands of customers, the knock on the door signifies convenience. But for Kader, a first-year undergraduate student at the National University, each delivery tells a story of resilience, ambition, and survival.

Kader's delivery zone stretches from Shewrapara through Kazipara to Mirpur-10 and Mirpur-11. It's a well-trodden path for him now, each alley and side road etched into his memory after months of experience.

The 22-year-old hails from Netrokona, far from the capital city of Dhaka. "I grew up in a farmer's family," he says softly.

"We don't own any land. My father cultivates other people's fields with help from my two elder brothers, who didn't get the chance to pursue education."

Kader is the youngest among his siblings and the only one studying at university. Determined not to let his dreams be buried under financial hardship, he moved to Dhaka and now lives in a small mess in Kazipara. The city may be expensive and unforgiving, but the opportunities it offers are vital.

"I needed a job immediately after coming to Dhaka," he says. "A few friends suggested becoming a delivery rider. It was the most practical option for me."

Unlike traditional part-time jobs such as private tutoring, working as a food delivery rider offers something essential: flexibility.

"There are rigid requirements in most jobs – fixed hours, strict schedules. I needed something that allowed me to prioritise my classes and assignments," he explains. "This job gives me that. I can work in the evenings or during free hours between lectures."

But the work is far from easy. Riders like Kader often endure long hours, poor weather, and physical strain, all while racing against time. The pressure to meet customer expectations and avoid penalties for late deliveries adds another layer of stress.

Still, Kader sees it as a stepping stone, not a destination.

"It's tough, yes. But it's helping me pay for my education, my living expenses, and a little bit I send home when I can," he says. "That means something."

Mehedi Hasan Babla's journey mirrors Kader's. Hailing from Northern Bangladesh district Nilphamari, Babla came to Dhaka with dreams of studying at Dhaka University. When admission to a public university slipped through his fingers, disappointed but undeterred, Babla enrolled at Titumir University College.

His limited savings, gathered by selling family belongings, quickly ran dry. "I had no choice but to find work," he said. "But how could I manage a job alongside my studies?

"Finding tuition jobs without connections is hard," he says.

He tried restaurant work in Khilgaon, an area now brimming with over 500 food establishments, before joining Foodpanda as a delivery rider.

Speaking to The Daily Star from the flat he shares with two other students in Khilgaon, Babla recounts juggling studies and deliveries, earning weekly, plus small bonuses.

"I began working part-time for Foodpanda in December last year. I do the evening shift, 5 pm to 10 pm, and earn Tk 2,200–2,300 weekly, plus bonuses for completing all orders."

Reflecting on one experience, he said, "An order came in from outside my zone. It was tough, but I didn't cancel. I delivered from Khilgaon to Tikatuli in old Dhaka."

Their stories reflect a broader trend: thousands of young Bangladeshis from rural, low-income backgrounds are entering the gig economy to sustain their education.

Platforms like Foodpanda, Pathao, Foodi and others offer flexible, part-time employment, and have become lifelines for students who need to earn without compromising their academic ambitions.

While the work is taxing and the pay modest, the opportunity to balance study and survival makes food delivery a stepping stone for many.

Bangladesh's online food delivery market is expanding rapidly, driven by shifting consumer preferences, digital advancement, and a rising middle class. Industry estimates suggest daily transactions of Tk 6 crore.

Yet, for all its early promise, Bangladesh's online food delivery sector has faced instability. Uber Eats was the first major platform to exit in June 2020, followed by Shohoz Food in 2021. HungryNaki, launched by local entrepreneurs in 2013, also shut down after struggling to compete with larger, better-funded platforms. E-food, owned by the collapsed e-commerce site Evaly, folded in 2021.

Industry operators the sector gained traction post-Covid, buoyed by increased urbanisation and a predominantly tech-savvy young population.

The sector directly or indirectly employs between 250,000 and 300,000 people -- many of them students and young workers including women, according to industry insiders.

Foodpanda alone works with over 100,000 delivery personnel, including 40,000 regular freelancers across all districts.

Ambareen Reza, managing director and co-founder of Foodpanda Bangladesh, attributed the growth to rising smartphone use and internet access, though she noted the market remains underdeveloped compared to neighbouring countries.

Challenges include poor supply chains, limited digital adoption, and sluggish expansion outside Dhaka, said the official of Foodpanda Bangladesh, operating as a subsidiary of Delivery Hero, is the leading food and grocery delivery platform in the country operating across 10 countries.

"One of the biggest challenges in this industry is ensuring a steady supply of delivery riders. Rider availability is crucial," said Mashrur Hasan Mim, chief marketing officer of Foodi.

Based on an estimated monthly market volume of 70,000–80,000 orders, Foodie currently holds around 20 percent market share, he claimed.

He said one major reason is the cost of maintaining a reliable rider base. "This is why so many companies fail to survive," Mim said.

"Customers often rebuke us for delays, but they don't realise we must collect food from specific restaurants first, which takes time," said Md Robin, a food delivery rider for Pathao.

"Some people understand, others don't. It's frustrating when we're abused despite doing our best," he added.

Originally from Barishal, Robin left school after SSC to support his family and worked at restaurants before joining Pathao two years ago. He operates in Tejgaon, Mohakhali, and Kakoli–Banani.

"This job suits me now," Mohammad Sagor Sarker, a third-year student at Titumir College, works evenings with Pathao.

"But it's not a long-term solution. When I have a family, this income won't be enough to meet needs and responsibilities."

Hailing from Kapasia, Gazipur, he chose the platform for its flexibility and lack of upfront costs. He earns around Tk 15,000 monthly to support himself and send savings home.

He shares a room in West Rajabazar, paying Tk 3,500 in rent. His father is a rickshaw puller and his mother a homemaker.

An official of a restaurant chain Pizza Burg from its Khilgaon branch said the restaurant sector has grown significantly, largely fuelled by the rapid rise of digital delivery platforms.

Many outlets now rely heavily on these services, with online orders often compensating for low footfall.

Similarly, Rabbani Hotel and Restaurant in Mirpur-10 has also embraced food delivery. Anisur Rahman, a staff member, said growing demand frequently results in queues of riders, occasionally causing slight delays.

Fahim Ahmed, managing director of Pathao, said, "Pathao is actively working towards establishing a safe, robust, and efficient framework that facilitates income-generating opportunities for individuals of all genders."

Customers' mixed reactions

Mirpur resident Saif Hasnat criticised poor packaging practices of some platforms.

"Items like rice and curry often arrive in polythene bags stapled shut – hardly hygienic or safe for hot, oily food."

Al Amin Hossain, a resident of the Mohammadpur area, expressed frustration with late deliveries.

"Riders blame traffic or restaurant delays, but the core issue seems to be platforms covering vast areas with too few riders. Customers then unfairly blame riders, even abuse them," he said. "Sometimes they withhold tips."

Another customer Abu Masum of the capital's Tejkunipara, warned against excessive commission fees set by the platform-based company. "If rates are too high, restaurants may choose to manage deliveries themselves."

Gig workers lack formal recognition

Mohammed Abu Eusuf, executive director of Research and Policy Integration for Development (RAPID), said food delivery is expanding as the economy grows and household incomes rise.

"This trend is visible not only in the West but increasingly in South Asia too.

"Urban mobility is time-consuming, and renting space for restaurants is expensive. Hence, takeaway and delivery services have become increasingly popular worldwide."

From the consumer side, convenience plays a key role. "People prefer eating at home rather than commuting through congested cities," he added.

Eusuf added that food delivery and ride-sharing are becoming key employment avenues. However, he said the sector must be formally regulated. "There's a policy gap regarding food safety and service standards," he concluded.

Ananya Raihan, chief imaginator at DataSense and a member of the Labour Reform Commission formed by the interim government, said workers in the gig economy lack formal recognition as labourers.

"They are referred to as independent entrepreneurs. Consequently, they are remunerated only when they work. If they do not, they earn nothing. They often spend the entire day waiting for clients," he said.

Furthermore, he said there are gaps in the labour law that allow these individuals to slip through the cracks.

"Although the nature of their work closely resembles full-time employment, they are afforded no legal recognition under national labour laws. They are designated as independent contractors and, due to this legal void, are excluded from key protections.

"For example, they do not receive wages, overtime pay, insurance coverage, or maternity leave benefits that are available to formally recognised labourers."

He added that as riders are not salaried employees, they must often work in excess of 100 hours a week to meet the minimum wage benchmark -- more than two and a half times the standard working week. "This inevitably results in significant health risks."

Furthermore, the pressure to deliver timely, with many platforms requiring delivery within 30 minutes to secure bonuses, increases the likelihood of accidents. There is rarely any compensation offered in such cases, he says, adding that most platforms do not provide accident insurance to their workers.

"As these individuals are not legally recognised as labourers, entitlements such as pensions, gratuities, and other employment benefits are non-existent. Simply put, they are not receiving what they justly deserve due to the absence of legislative protections," he said.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments